Nonviolence

“For to us a child is born, to us a son is given,” Isaiah prophesies of the coming Christ child — a child who will be called “Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6). That Prince of Peace would later proclaim in his Sermon on the Mount, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God” (Matthew 5:9). Advent calls us to explore how we can pursue peace in our own lives — how we can better become instruments of peace in our communities, nation, and the world. Right now, the prospect for peace feels particularly challenging in light of an ongoing pandemic, rampant violence, and intrastate conflict across the globe.

HISTORY HAS PAID personal attention to Lawrence Joseph, a Maronite Catholic from Detroit. In 1967, when Joseph was 19 and just finished with his freshman year at the University of Michigan, his father’s grocery-liquor store was looted and burned during the Detroit Rebellion. The five-day uprising of Black people reacting in part to police abuse and brutality and its fierce suppression by law enforcement and the National Guard made him “acutely conscious of America’s deeply systemic violence.”

Joseph, a poet who was also a lawyer who taught at St. John’s University in Queens, N.Y., and at Princeton, was living a block from the World Trade Center in 2001 when the two planes attacked. He and his wife had to evacuate their apartment. It was weeks before they could return. In the title poem of his 2017 volume So Where Are We?, Joseph writes:

flailing bodies in midair—

the neighborhood under thick gray powder—

on every screen. I don’t know

where you are, I don’t know what

I’m going to do, I heard a man say;

the man who had spoken was myself.

“I GRADUATED FROM university in 1968. I was drafted immediately. I had not really thought much about the war, but the more I talked to the guys who were coming back from Vietnam, the more I realized that this thing was terribly wrong. I began to think of the Vietnamese forces as liberation forces trying to free their country from foreign invasion—we were the invaders.

I went through a crisis of conscience. I saw a news report about soldiers who were speaking out against the war. I thought to myself, I can do that. I began to organize among soldiers in the barracks. We submitted a petition signed by 1,300 active-duty service members that was published in The New York Times.

The basis of my commitment to activism is faith: the belief that our role in life is to serve others, to overcome suffering and injustice, especially war, which to me, is the greatest sin."

AFGHANISTAN HAS BEEN in conflict for more than 40 years. The former Soviet Union sent in more than 150,000 troops on Christmas Eve 1979 and left 20 years later. The U.S. began a massive bombing campaign in October 2001, the first stage of the war to oust the Taliban. Now, 20 years later, the U.S. has withdrawn the last American troops. It is hard to find a single Afghan, including myself, who hasn’t been a victim of the ongoing conflict.

As Afghans know, parties in these battles change, but the outcomes—devastation and killings—remain the same. Ordinary Afghans, as we have seen with the recent Taliban resurgence, pay an immeasurable price. They are killed, bombed, displaced, and disabled. However, the voices of these ordinary people are rarely heard. Perhaps they no longer raise their voices. What speaks loudly is their pain and sorrow.

Despite numerous formulas and prescriptions for ending bloodshed and oppression in Afghanistan, violence remains. Most solutions were formulated by the elite class. They are the ones in the driver’s seat. They make decisions as they please. The wishes of ordinary Afghans are nowhere to be found.

After 20 years of war and violence under four different presidents — and the deaths of more than 172,000 people — the United States withdrew its last troops from Afghanistan on Monday.

For many, ending the war in Afghanistan seems like a step toward a more peaceful future. But even in the process of ending a war, the United States has relied on violence to enforce its will.

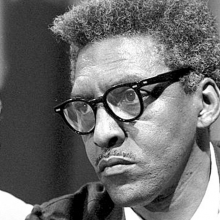

Rustin, who died in 1987, is best known for helping Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. implement Gandhian tactics of nonviolence and for the key role he played organizing the 1963 March on Washington and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — two key components of the civil rights movement.

Less well-known are the particularities of Rustin's faith, including his deep roots in the Quaker and African Methodist Episcopal churches which drove his activism. Those two faith traditions, marked by silence and singing, respectively, echoed throughout Rustin’s life and work.

NONVIOLENCE. WHEN YOU hear the term, what do you think? In your mind’s eye, what do you see? Black and white newsreels of college students dressed in their Sunday best, picketing segregated businesses? Perhaps you imagine Gandhi’s historic salt march to the sea or Martin Luther King Jr. leading the faithful onto the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

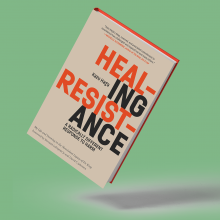

It’s not uncommon to hear “nonviolence” and think “protest.” There is much value in this association. History demonstrates that nonviolence can be an effective tactic for promoting political change. But in Healing Resistance: A Radically Different Response to Harm, Kazu Haga shows us that it can be much more than a political tool.

Haga—a nonviolence trainer and founder of East Point Peace Academy in Oakland, Calif.—was influenced by the Kingian nonviolence principles and curriculum of Bernard LaFayette Jr. and David C. Jehnsen (who co-wrote this book’s foreword). Haga weaves these principles with lessons from Buddhism, social justice activism, and trauma work, illustrating how we might embrace nonviolence to transform both ourselves and our world.

Ahead of President-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration, monuments are fenced off, streets are closed and 20,000 National Guard members are positioned around Washington, D.C. But some local organizations are more focused on the safety of Washingtonians — especially the safety of Black and brown Washingtonians who may be at greater risk of being targeted by right-wing groups, many of which have ties to white nationalism.

As this uncertain post-election period continues in the United States, we must be prepared to help calm communities, prevent violence, and protect each other through disciplined and strategic nonviolent action.

According to a recent survey, nearly 70 percent of people in the U.S. are worried voters will be harassed or intimidated on Election Day; the same survey found that more than three-quarters of Americans worry there will not be a peaceful transition of power after the election. But community leaders and clergy are determined to avoid a violent outcome.

People of diverse faiths have a moral obligation to protect the integrity of the election. Right this minute, people all across the country are voting early or by mail, or making plans to vote in person. As religious and spiritual leaders, we are prepared to take to the streets peacefully if it becomes clear that votes are not being counted or if a legitimate election outcome is being subverted.

NONVIOLENT PEACEFORCE is an international nonprofit that works with communities facing violence to implement nonviolent strategies to help keep them safe. They have worked with communities around the world, including in Sri Lanka, Iraq, South Sudan, and Guatemala. Mel Duncan, Rosemary Kabaki, and Jessica Skelly of Nonviolent Peaceforce spoke in mid-September with Sojourners’ Betsy Shirley about their newest project location: the United States.

Sojourners: Why did you start projects here in the U.S. this fall?

Mel Duncan: We recognize that right now there are many indicators of looming violence, whether it be strife over police brutality and racism, or the chaos that is being stirred up around the election, or the catastrophic experiences we’re seeing with climate change—all of these can trigger violence.

What risks do you see?

Jessica Skelly: As we look toward the elections and beyond, we can see some indicators for flashpoints of violence—election tampering, delays in the election, perhaps continued police brutality, instigation by agents provocateurs—and people want to know how they can mobilize in responsible and constructive ways and help de-escalate some of that violence and protect themselves.

The words of Jesus must now be taken seriously, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.”

The attack by a U.S. MQ-9 Reaper drone that fired missiles into a convoy carrying Soleimani was neither impulsive nor a retaliatory response. It was not undertaken to protect Americans. It was not an act of patriotism. It was not done to defend the U.S. embassy in Baghdad after the “dramatic but bloodless” siege. If anything, it was in response to Trump’s increasingly untenable situation at home.

Pope Francis wrapped up a four-day trip to Japan on Tuesday by turning from the anti-nuclear message that was the backbone of his visit to other key campaigns of his, urging students to defend the earth and show greater compassion.

“Blessed are the peace lovers,” for they shall be called righteous — on the right side. They will be known for what they will not do, for being against war, for preferring peace, for not fighting, for staying out of conflicts.

But that is not what Jesus said.

f you’ve checked your social media recently, you may have noticed profile pictures with a blue background. This is how some are showing solidarity with the peaceful demonstrators in Sudan who, in the face of extreme violence and a near-total internet blackout, are demanding a civilian government.

Last December, the Sudan Professionals Association (SPA), an umbrella organization of trade unions, organized a large demonstration in Khartoum, the nation’s capital, focused on the dire economic situation in the country. The public outpouring grew as people took to the streets in more than 90 locations throughout Sudan. These new protests, triggered by price hikes and food shortages, quickly developed into anti-government protests and inspired even more actions around the country. The SPA decided to change its target: Instead of focusing on the economy, the SPA began to demand the removal of the military-led regime.

Sudan is not new to nonviolent revolutions. The Sudanese took to the streets in organized mass demonstrations and general strikes that ended dictatorships in 1964 and 1985.

When the U.S. Capitol Police issued three warnings for us to disperse, most of those gathered stepped back behind the police line, but five stepped forward and laid down in the shape of a cross in the center of the rotunda. A cross of human bodies. Dozens more formed a eucharistic circle around this cross.

THE U.S. HAS BEEN on a war footing since at least 1939. Undergraduate students today have never known a world before 9/11, and even their instructors (I was born in 1983) have never known a peaceful America. The Cold War era that preceded our own was enormously bloody in places such as Lebanon, Vietnam, and Afghanistan—and in all these countries, American intervention played a role.

During the Cold War, permanent war footing seemed like more of a threatening novelty than a grinding inevitability. The time played host, therefore, to a global and surprisingly influential peace movement. The Politics of Peace tells the movement’s dramatic story of both ideals co-opted and maybe even betrayed and ideals that shaped our world and might be worth recovering.