Jul 26, 2021

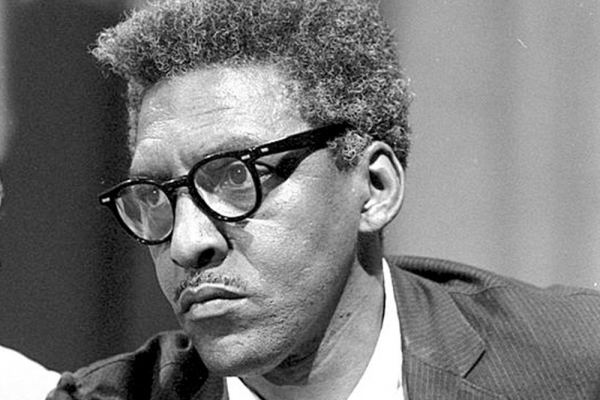

Rustin, who died in 1987, is best known for helping Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. implement Gandhian tactics of nonviolence and for the key role he played organizing the 1963 March on Washington and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — two key components of the civil rights movement.

Less well-known are the particularities of Rustin's faith, including his deep roots in the Quaker and African Methodist Episcopal churches which drove his activism. Those two faith traditions, marked by silence and singing, respectively, echoed throughout Rustin’s life and work.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login