Feature

They were U.S. “torture taxis” in the years after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

Playing a key role in the CIA’s “extraordinary rendition,” detention, and interrogation program, the two aircraft flew at least 34 separate “rendition circuits” that resulted in the kidnapping, imprisonment, and torture of at least 49 individuals, according to the U.K.-based Rendition Project, a coalition of academics, human rights investigators, legal teams, and investigative journalists who waded through reams of data, including falsified and redacted flight plans and other reports, to uncover the truth about the CIA program and its victims.

A typical flight circuit, according to The Rendition Project, went like this:

- A jet would take off from Johnston County Airport, about 30 miles south of Raleigh, and fly to Washington, D.C., to pick up the CIA “snatch team.”

- It would then fly across the Atlantic and stop for refueling somewhere in Europe.

- The next stop would be the pick-up location, often in Afghanistan or Pakistan, but also in Egypt, Gambia, Morocco, Malawi, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Djibouti, Macedonia, and elsewhere.

- Dummy flight plans would often be filed to obscure the true drop-off destinations, which included the Guantánamo Bay detention center in Cuba, CIA “black sites” in Poland, Romania, Afghanistan, and Lithuania—and one in Thailand that was run by now CIA director Gina Haspel.

- After delivering the prisoner, the plane would fly to a “rest and relaxation” location to refuel and to allow the CIA team to recover before being flown back to Dulles Airport near Washington, D.C.

- The final leg took the plane and flight crew home to Johnston County.

The commission against torture is following the lead of previous truth commissions, including its own state’s Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission and another focused on the 1898 Wilmington race riot—both of whose members and staff provided advice. The independent, nongovernmental torture commission held public hearings in November and December to investigate and encourage public debate about the role North Carolina played in facilitating the U.S. torture program between 2001 and 2006.

TWO-THIRDS OF A CENTURY after the Korean War, most Americans do not know what happened in that conflict or how it impacts the Korean Peninsula even today.

In 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea. The U.N. intervened, and in the three years that followed the U.S. Air Force dropped more tonnage of bombs on North Korea than were used in the entire Pacific theater during World War II, including more than 30,000 tons of napalm. The U.S. destroyed 80 percent of the North’s infrastructure and 50 percent of its cities. The capital city of Pyongyang was wiped off the map.

“Over a period of three years or so, we killed off—what—20 percent of the population,” said Air Force Gen. Curtis LeMay, head of the Strategic Air Command during the Korean War. Historians believe that between 70 and 80 percent of the deaths were civilians.

Nearly 40,000 U.S. soldiers died and more than 100,000 were wounded in what has been a “forgotten war” in the United States. North Koreans, however, have never forgotten the war that resulted in millions of casualties in their country. For 65 years, they have lived under that war’s vivid memory and evolved into one of the most militarized states in the world.

The root causes of the problem

Technically, the Korean War never ended. The armistice treaty signed in 1953 reinstated the government of South Korea, suspended open hostilities, created the Demilitarized Zone, and allowed for the release of prisoners of war, but it was not a permanent peace treaty between nations. No peace treaty has ever been signed. “We have won an armistice on a single battleground—not peace in the world. We may not now relax our guard nor cease our quest,” said President Dwight Eisenhower.

AMERICA HAS A CRISIS of mass incarceration, and it has little to do with crime rates. The system is broken: America imprisons more of its citizens than any other nation in the world. Even though the United States contains just 5 percent of the world’s population, the nation has nearly 25 percent of the world’s prisoners. At every point, from the laws on sentencing to policing practices and health conditions in prisons, impersonal forces exact a very personal toll on incarcerated persons and their families.

Many citizens have started to work on solutions by raising awareness, legalizing drugs such as marijuana, and passing laws that require police officers to wear body cameras. But one critical function of our legal system has received too little attention from Christians and the rest of the public: local prosecutors.

Local prosecutors, or district attorneys, as they are formally known, hold enormous influence. These 2,400 individuals nationwide have the authority to determine when, how, and how severely to charge a person with a crime. They help determine when someone goes home and when someone goes to prison for decades. Their decisions could mean the difference between an innocent person going free or going on death row.

I first became aware of the issues related to local prosecutors while attending a lecture at the University of Mississippi in fall 2017. I was there to hear James Forman Jr. talk about his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America, which describes how black Americans, for complex reasons, supported the “tough on crime” policies that led to mass incarceration. During the Q&A that followed Forman’s lecture, one student asked Forman how nonlawyers could join in the effort to reform the criminal justice system. A part of Forman’s response remained with me.

“Get involved in local races,” he said. “Local prosecutors are the most powerful people in the system, but nobody votes in these races.”

MY THROAT STARTED to feel tight a few days before I went to Montgomery this April. I had been planning this pilgrimage to Alabama with my teen children for months but, as the days grew closer, I questioned my body’s ability to walk into the grief that was awaiting us at the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

As a biracial African-American woman putting down roots in the rural South with my white husband and our four children, daily life can feel like an act of resistance. Every day we are faced with Confederate flags and memorials that celebrate an era and mindset that would have made our marriage and my equal ownership of our property a crime. But we love our home, the land, and our neighbors. We want, in the words of Gwendolyn Brooks, “to conduct [our] blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.”

I was determined to bring my older children to the state of my birth, to take an unflinching look at our racist past and present, and to give them courage to walk the unfinished path toward justice. But still, I found it hard to breathe.

I gardened with a single-minded ferocity in the days before our trip, pulling weeds and digging up long taproots as though I could purge the evils from our land with my bare hands. Red dirt began to lodge deep beneath my nails and in the dry creases of my fingers, my forearms bore slashes from the thorny vines that whipped me as I tore them from the earth. There were flowers, thick with the hopeful scent of spring, trying to bloom beneath the tangle of weeds. I yanked and tore in every spare minute I had, stopping only when I noticed blood pouring from a deep slice on my right forefinger.

It felt right to come with dirty, bloodied hands into those sacred spaces in Montgomery.

EVANGELICALS IN THE United States and Christians in the Middle East had vastly differing responses to President Trump’s actions on Jerusalem that sparked the explosion of violence this spring on Gaza’s border with Israel.

In the United States, 53 percent of evangelicals supported the decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, according to a Brookings Institute poll, and it was greeted with unadulterated joy by prominent leaders of the Religious Right. A wide range of church leaders in the Middle East were decidedly less positive about Trump’s actions, pointing to the potential threat not only to peace in the region but also to the very presence of Christians in the Holy Land.

How could an action so many U.S. Christians supported elicit such opposition from Christians across the denominational landscape of the Middle East?

There are, of course, deep divides within Christianity about the place of the Holy Land and role of the Jewish people in eschatology that in part explain the divergent reactions, but there are pragmatic reasons as well for why Middle Eastern Christians would oppose the Trump administration’s actions on Jerusalem. The U.S. government’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel—absent a peace agreement between Israelis and Palestinians—will certainly threaten the Christian presence in the city and increase the risk of violence, according to church leaders there, owing to the unilateral nature of the decision.

Supporters of U.S. recognition of Jerusalem might ask how this seemingly symbolic act could harm Christians (or anyone, for that matter). The Trump administration, after all, denies that the recognition of Jerusalem will have any detrimental impact on the peace process. They argue that Jerusalem has served as the physical location of Israel’s government since 1950; it makes no sense, they say, to deny the reality that the city is “in fact” Israel’s capital.

IN THE FIGHT against gerrymandered electoral districts in Pennsylvania, Carol Kuniholm is a rock star.

A former English professor and youth pastor, Kuniholm now spends much of her time traveling the Keystone State, explaining to hundreds of listeners how politicians have deliberately redrawn Pennsylvania’s voting districts to favor their own party. Using charts and graphs, Kuniholm shows, in lucid detail, how the disfigured districts chill democracy. “Democracy means voters choose their politicians,” explains the website of Fair Districts PA, an anti-gerrymandering organization Kuniholm co-founded in 2016. “Current Pennsylvania law lets politicians choose their voters.”

Plain-spoken and precise, Kuniholm hasn’t changed her demeanor since taking charge of the state movement, though she did make one concession to her newfound fame: “I bought a suit,” she confesses.

MANY PEOPLE TALK about the injustices in the world but do nothing to rectify them. This can’t be said about the following five leaders—pastors, activists, lawyers, businesspeople, and artists—who Sojourners will recognize as “movement honorees” at the June 13-15 Summit 2018. These innovators are doing what Jesus did: taking God’s vision of the world and spurring others toward that ideal. Rev. Brittany Caine-Conley

Rev. Brittany Caine-Conley

“I learned pretty early about myself,” Caine-Conley told Sojourners, “that the concepts of justice and righteousness were really important concepts to me.”

Cue Aug. 12, 2017. While much of the nation watched from afar the racially charged violence in Charlottesville, Caine-Conley encountered the physical threats in person as she protested the white nationalist rally in her city. Caine-Conley and other protesters were shoved by supporters of the Unite the Right rally. And the car that a Nazi sympathizer plowed—apparently on purpose—into a crowd of protesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer, also injured an affiliate of Congregate Charlottesville, the local faith-based social justice network Caine-Conley, United Church of Christ minister, helped organize.

“It was the most horrible thing I’ve ever experienced,” Caine-Conley said to Vox about seeing the wounded, who were lying in the street in the car’s wake.

And yet Caine-Conley believes it is her duty to be wherever tragedies like this happen—to put herself in harm’s way.

IN MARCH 2015, as video after video of police violence flooded the nation with outrage, grief, and hashtags, an unarmed homeless man named Charly “Africa” Keunang was shot and killed in downtown Los Angeles by the LAPD. In a city still bearing scars from the ’92 uprising that followed the beating of Rodney King on live television, Ferguson and all that followed was but the latest reminder of what happens when black grief is met by a militarized police force.

As a young pastor in downtown LA, I wanted to respond but didn’t know how. After reaching out to local community leaders for wisdom, I called Officer Deon Joseph, a 20-year veteran of the LAPD, adored by some and abhorred by others on Skid Row. Together, we agreed to form a team of pastors, officers, and community members to restore trust between the community and the police. We held a community vigil to honor Brother Africa and hundreds came; the officers in attendance bitterly wept.

Excited and nervous on his first day of high school in Leskovac, Serbia, Saša Bakic waited his turn to introduce himself. After he said his name, his new teacher stopped him: “Are you Roma?” she asked. “Let’s make a deal—if you don’t skip school and stay quiet in class, I will pass you with a D.” Stunned and humiliated, Saša tried to protest amidst the class’s laughter, only to be told, “You are all the same.”

The history of the Roma—Europe’s largest minority—is pockmarked with stories of forced assimilation, enslavement, and even attempted genocide during WWII. Today, despite efforts of state and EU policy toward integration, many Roma in Eastern Europe are still mired in systemic poverty and social stigma.

The steady growth of Roma Pentecostalism in Europe, however, is another narrative challenging these sobering realities.

When Saša began attending church at age 8, he received a message of acceptance and encouragement. “The children’s sermons acknowledged that we were outcasts, but that we should love rather than hate,” he remembered, now working to complete his bachelor’s in theology. “The church told us, ‘Let’s make a better image of our community!’”

The German National Tourist Board has fallen in love with Martin Luther. In 1517, he nailed 95 theses protesting Catholic Church practices to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg, an act considered the start of the Protestant Reformation. In honor of the 500th anniversary of this event, a 36-page tourist board brochure outlines eight different routes you can take through Germany featuring “36 authentic Luther sites” with itineraries offering “surprises aplenty.” They’ve even produced a Luther Playmobil figure for ages 4 through 99.

Reformation anniversary observances officially started in October in Lund, Sweden, with an ecumenical worship service convened by the Lutheran World Federation and the Vatican, attended by Pope Francis. Since then, countless events, conferences, exhibitions, and observances are being held not just in Germany but around the world as we approach the official anniversary day, Oct. 31, 2017.

But what exactly should we Christians do on this 500th anniversary of the Reformation? Celebrate? Commemorate? Confess? Or repent?

The impact of the Protestant Reformation, combined with the advent of the Gutenberg Bible and the dramatic increase in printed literature and literacy in Europe, produced revolutionary changes in religion and society. As the German tourist board exclaims, “trade, industry, art, architecture, medicine, and technology flourished like never before.” A glowing narrative of the Reformation’s impact on the church and Western culture tends to dismiss any words of thoughtful critique.

In Kolkata, India’s second largest city, mass poverty affects millions. More than a third of the region’s 18 million people live in slums and 70,000 are homeless. Street and slum dwellers in Kolkata are mostly refugees or migrants from rural areas, driven into the city in search of livelihood. Whole families live in fragile shanties, bus shelters, and railway platforms, earning a meager living as rag pickers, petty hawkers, and daily wageworkers. Trapped in a vicious poverty cycle, they struggle daily for survival.

But it is also the site of broad-scale social programs rooted in Pentecostal faith.

“First feed our bellies ... then tell us about a God in heaven who loves us!” Decades ago, a hungry beggar flung these words at Mark Buntain, a young missionary-evangelist from North America who, with his wife, Huldah, had come to share the good news of Jesus with the people of Kolkata. The Buntains were convicted by these words, and the Assembly of God Church they founded 60 years ago launched a social outreach program that has served the poor of Kolkata ever since.

The Kolkata Assembly of God Church’s theory of change is deeply rooted in the gospel of Christ, with our ultimate goal being fullness of life for all, especially for the poor and marginalized in society. Though our initial response to the poverty trap was a spontaneous attempt to meet immediate needs at the grassroots level, with time we also developed a more studied response geared toward sustainable empowerment.

FRANTICALLY GRABBING last-minute items, I rush out the door to get my middle-school son to his pregame warm-up. “Oh, don’t rush; it will only take us 25 minutes to get there,” says my son. Surprised, I question where he got that information. Looking up from his phone, he replies, “Google sent a notification on my phone since my calendar has the game with location.” With some marvel in his tone, he remarks, “Every morning Google Assistant tells me how long it will take the bus to get to school.”

Humans have always shared information with each other, but the advance of digital media altered the time and geographic constraints that once shaped our historical patterns of communication. This transition ended the “Gutenberg era,” a period of human communication marked by a dependency on print, authorship, and fixity, and launched us into an era of communication marked by openness, collaboration, and easy access to information.

Despite the rapid pace at which we churn through this information, our new communication styles are also shaped, paradoxically, by permanence. Every share, post, or comment is archived, creating an online trove of information that identifies every person and their connections: where we get our news, what we look like, what sports team or social causes we support, who “likes” our church on Facebook, and, in my son’s case, our current whereabouts, our travel route, and destination points.

The internet is forever

In the world of digital ethics, the “endless memory of the internet” has recently attracted a lot of attention. How do we live in a world that increasingly does not forget?

The religious ideas and practices of the Indigenous peoples of Bolivia, primarily Quechua and Aimara, flow like a subterranean stream through the country’s dominant Catholicism, particularly in La Paz, the most culturally Indigenous capital city in Latin America.

But evangelical Christianity, brought to Bolivia by European and North American missionaries more than 100 years ago, has also maintained a relationship with Bolivian culture—and that culture has shaped the church even as evangelicals have increased in numbers and influence.

Evangelical and other Protestant denominations, especially the neo-Pentecostals, have reached out to Aimara Indigenous communities, even while respecting fundamental components of Aimara ethnic identity. Thus while a chauvinism rooted in both national tradition and missionary evangelicalism dominates most male-female relationships in much of Bolivia, within Aimara neo-Pentecostal families, gender relations are more symmetrical.

Partly as a result of these cultural values, Indigenous women play important leadership roles within many neo-Pentecostal churches and organizations. They speak their own language in services and adopt symbols and rituals that come from their own Indigenous identity rather than European Protestant tradition. Whether it is recognized or not by outsiders, the Aimara identity proposes new ways of living and representing the Christian faith. Through the meeting of Aimara culture and neo-Pentecostalism, the assumption of male hierarchy is being questioned and subtly transformed.

My grandparents supported Trump.

Their simple white house sits on the sprawling plateau between Joplin and Springfield, Mo., just around a bend in the country road where their church stands. It’s not more than a mile from the old farm, where my grandpa raised chickens and tilled the soil until his body would no longer allow it, as the man who owned the land had promised he could. To me, he’s always been Papa, but in that remote part of the Ozarks he’s known as the “chicken man,” a name in which he delights.

Papa has never been a very good businessperson. When at first he went to sell the fruits of his labor, he would put out a can and ask people to pay what they could. Eventually he fixed prices to things, but when the woman who was raising her grandchildren alone would show up, she knew that whatever she could spare was enough. “Don’t try to outgive the Lord, because you can’t,” Papa told me on countless occasions. In order to make ends meet, he used to work at the nearby quarry. Now he cares for the church building next door and, in exchange, the congregation lets him and grandma live in the house.

When I was in high school, I spent part of a summer on the farm, where I learned all sorts of things firsthand: that picking okra is sticky work, that spiders have an unfortunate affinity for tomato plants, and that unvarnished racism is still acceptable in certain quarters. It was the first and only time I remember meeting my great-grandma. She brought her new husband, Joe, with her, and at one point in the conversation he made clear he was not happy about the “Oreo cookie” families moving into the area. Still to this day, if you bring Joe up in the presence of my grandma, she’ll tell you she never truly accepted her mother’s last beau. He was too “mean.”

THE WORLD INTO WHICH we preachers cast our voices is already the world claimed, sought, and being reclaimed by Christ. For a white preacher to risk talk about race is an act of faith in the transformative resourcefulness of the Trinity. When it comes to the great divine-human contest with our sin, including our sin of racism, God will have the last word: “Come to me” conjoined with “Follow me.”

While preaching can’t do everything, God has chosen preaching as weapon of choice in the divine invasion and reclamation of creation. Theologian Richard Lischer says that Martin Luther King Jr. “believed that the preached Word performs a sustaining function for all who are oppressed, and a corrective function for all who know the truth but lead disordered lives. He also believed that the Word of God possesses the power to change hearts of stone.”

Preaching is one of the means through which God defeats our natural narcissism.

Theology, not anthropology

Much of my church family wallows in the mire of moral, therapeutic deism, a “god” whom the modern world has robbed of all agency. Ta-Nehisi Coates begins his riveting Between the World and Me by announcing that he is an atheist. Between the World and Me is an honest but brutal, sorrowing, eloquent, hopeless lament for the intractability of American racism. Coates castigates those African Americans who speak of hope and forgiveness.

It must have been an odd thing, being the Holy Roman Emperor in June 1530, making the long trek to the Bavarian city of Augsburg to meet with a league of rebel states. But this is where Charles V found himself. Stranger yet, he was doing this not to convince these leaders to form a military alliance (though he was hoping to confirm their military fealty), nor to advocate for trade deals or relish the verdant Bavarian countryside.

Instead, the most powerful man in Europe had come to talk theology, with the hope that he could reunite a church fractured by the teachings of a rebel monk and a novice professor a mere 13 years earlier, in 1517. A monk who had since been condemned for heresy and treason in the 1521 Edict of Worms, but who—thanks to his ruler, Frederick III of Saxony—had nonetheless been hiding safely in plain sight ever since.

That wily monk, of course, was Martin Luther.

Thankfully, Luther and his supporters were relegated to the imperial backburner after the Diet at Worms, an imperially sanctioned assembly of the Holy Roman Empire, as global political matters and internal quibbling between testy royals kept Charles busy between 1521 and 1529. So the “Lutherans,” as they began to be called, took advantage of those years to thoroughly educate the priests and populace of Saxony about the most central of Luther’s teachings—the Doctrine of Justification: People “cannot be justified before God by their own strength, merits, or works, but are freely justified for Christ’s sake, through faith, when they believe that they are received into favor, and that their sins are forgiven for Christ’s sake, who, by His death, has made satisfaction for our sins. This faith God imputes for righteousness in His sight (Romans 3 and 4).”

LAST SUMMER, THE FUTURE of for-profit prisons seemed bleak. The U.S. Department of Justice announced it would begin phasing out its use of privately run prisons and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security quickly followed suit, declaring that it would reconsider its use of privately run detention centers. Stocks for companies that ran for-profit prisons plunged.

But then Donald Trump was elected president, and private prison stocks immediately soared. The nation’s largest prison company, CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America), reported a boost of more than 40 percent in the value of its shares. Given Trump’s promises to “create a new special deportation task force,” investors bet that privately run detention centers will play a key role.

And the investors may be right. Every year, DHS detains about 400,000 undocumented immigrants in 250 centers nationwide, and 62 percent of the beds in these centers are operated by for-profit corporations.

According to Maria-José Soerens, a licensed mental-health counselor serving undocumented immigrants in Seattle, there are two major problems with for-profit detention centers. First, for-profit centers are not held accountable to the standards that govern federally run centers. In her work in these centers, Soerens has heard complaints ranging from a lack of medical attention to inadequate opportunities for parent-child visitation; one young woman who was having suicidal thoughts was kept in solitary confinement until she told guards she was “better.”

But the deepest problem, explains Soerens, is that most detention centers only exist because corporations saw a “business opportunity.” Beginning in the early 2000s, for-profit prison companies successfully lobbied Congress to expand drastically the number of beds in the immigration detention system—a move that doubled the revenue of the two largest for-profit prison companies. In 1998, there were 14,000 beds available for immigrant detention; today, there are 34,000.

LONG BEFORE Boko Haram emerged in 2002, my home country of Nigeria was polarized along religious and ethnic lines by politicians who sought to pit one group against another. Disputes about religious freedom, resource control, and citizenship led to violent conflicts at the local and state levels. Many religious sites were desecrated.

Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa and seventh most populous worldwide, is fondly referred to as “the giant of West Africa.” It has the largest economy on the continent and is incredibly diverse in ethnicity and religion. Half of Nigeria’s population is Christian, living mostly in the southern part of the country, and the other half is Muslim, living primarily in the north.

In 2009, while I was pastor of a Catholic parish in Kano State, in northern Nigeria, a bloody confrontation broke out between the Nigeria Police Force and Boko Haram about 300 miles away in the northeast part of the country. Two years later, I was caring for eight families who had fled to the city of Kaduna, seeking safety from Boko Haram attacks. As I listened to their stories, I could not help but think of my own family’s displacement after riots in 1980 and 2002. Our congregation and my own family had been directly impacted by violent ethno-religious conflicts.

But the norm in the part of northern Nigeria where I grew up was very different from that. Christians and Muslims lived together as neighbors and friends. Young people bonded as they played sports with one another. Muslims and Christians exchanged greetings and attended one another’s naming and marriage ceremonies. We rejoiced and grieved together.

This included Nasiru, Ahmad, and Abdul, three of my Muslim neighbors who joined Boko Haram in 2009. They were attracted to Boko Haram because of their frustration with overwhelming socioeconomic inequality that had left them impoverished and unemployed. From their perspective, the ostentatious lifestyle of the political class indicated corruption, poor governance, and improperly managed resources. Boko Haram seemed to promise justice.

“We feel hopeful when the preacher reminds us that those who rob us of our livelihood will be judged and damned,” I remember Nasiru saying to me.

"REMEMBER YOU are dust, and to dust you shall return.” Each year the community of Jesus stands at the beginning of the season of Lent and recalls death, mortality, corporeality. We are dust. We are dying. And, as the pastor smears the mark of the cross on the foreheads of the faithful on Ash Wednesday, she says, “Remember you are dust.”

Such an awareness is where resurrection hope begins. It must. How can one celebrate resurrection hope without first understanding that we are dust and to dust we shall return? The act of marking ourselves with ashes is not morbid. Such rituals of death and resurrection give witness to God’s grace for both the dead and those who love them.

But what happens when there is no body over which to mourn?

In circumstances where a loved one’s body is lost, the pain and grief are magnified. A plane disappears over the depths of the waters, and bodies are never found. A person goes missing, and remains are never recovered. Whatever the circumstance, a funeral without a body is almost always a source of extra pain. Not only is a loved one dead, but the ritual act of tending to their body is taken away.

There are people in the United States, Mexico, and Central America who experience such trauma largely because of U.S. border policy. As people die migrating through the desert lands of the southern border of the United States, their bodies are literally returning to dust, and their suffering is largely invisible. Rather than receiving ritual care from family and community at the time of death, these immigrants die alone. Their remains are left in the desert, discovered only by chance.

A humanitarian crisis at the border

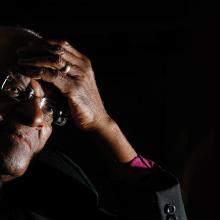

I FIRST HEARD Archbishop Desmond Tutu speak at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., sometime around 1987. It was at the height of apartheid in South Africa, and the world was just waking up to its horrors and organizing global economic sanctions.

Tutu spoke of an elderly woman he had met a few days earlier in Soweto. She told him that every night she got up at 2 a.m. for an hour in order to beg God solemnly for an end to apartheid. “I know we will win now,” Tutu told us, “because God cannot resist the prayer of that poor old woman.” With that, he burst into tears. Those tears of peace converted the thousands of us who crowded in to hear him. We had never heard such a witness for peace.

Later, I came to know him as a friend. During my 2014 pilgrimage to South Africa, I spent a morning visiting the great man at his foundation headquarters in Cape Town. First, we had Mass together with his staff; then he catered a brunch for me and my friends. He and I helped ourselves to a plate of food and coffee, then sat together by ourselves for an hour.

“We do not have the right to give up this work,” he told me. “Our sisters and brothers are suffering around the world, so we have to keep working for peace and justice till the day we die.” I was amazed to hear that he planned to leave the next day for Iran. He was in his 80s, in bad health, and relentless.

He spoke of the millions of squatters living in total poverty around Cape Town and elsewhere. “We have the ultimate First World wealth and the worst Third World poverty, the biggest gap between rich and poor in the world,” he said. “One percent of the money for war and nuclear weapons could feed and house these poor people. Sometimes I say to God, ‘What the heck is going on? Why don’t you do something?’”