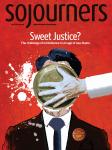

EVANGELICALS IN THE United States and Christians in the Middle East had vastly differing responses to President Trump’s actions on Jerusalem that sparked the explosion of violence this spring on Gaza’s border with Israel.

In the United States, 53 percent of evangelicals supported the decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, according to a Brookings Institute poll, and it was greeted with unadulterated joy by prominent leaders of the Religious Right. A wide range of church leaders in the Middle East were decidedly less positive about Trump’s actions, pointing to the potential threat not only to peace in the region but also to the very presence of Christians in the Holy Land.

How could an action so many U.S. Christians supported elicit such opposition from Christians across the denominational landscape of the Middle East?

There are, of course, deep divides within Christianity about the place of the Holy Land and role of the Jewish people in eschatology that in part explain the divergent reactions, but there are pragmatic reasons as well for why Middle Eastern Christians would oppose the Trump administration’s actions on Jerusalem. The U.S. government’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel—absent a peace agreement between Israelis and Palestinians—will certainly threaten the Christian presence in the city and increase the risk of violence, according to church leaders there, owing to the unilateral nature of the decision.

Supporters of U.S. recognition of Jerusalem might ask how this seemingly symbolic act could harm Christians (or anyone, for that matter). The Trump administration, after all, denies that the recognition of Jerusalem will have any detrimental impact on the peace process. They argue that Jerusalem has served as the physical location of Israel’s government since 1950; it makes no sense, they say, to deny the reality that the city is “in fact” Israel’s capital.

The fact of the matter is that Jerusalem’s status is disputed. Israel’s definition of the municipal limits of the city differs from those recognized by the international community. Even the United Nations, the European Union, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, and Pope Francis have condemned the Trump administration’s position regarding Jerusalem.

America’s most prominent Christian Zionist politician

Since the beginning of his career in politics, Vice President Mike Pence has made it clear to his constituents that his Christian faith informs his political views, including his positions on U.S. foreign policy. In a now-infamous 2002 interview with Congressional Quarterly, while Pence was serving in Congress, he said, “My support for Israel stems largely from my personal faith. In the Bible, God promises Abraham, ‘Those who bless you I will bless, and those who curse you I will curse.’”

Not unexpectedly, visiting Israel and meeting with Christian minorities in the broader Middle East has been at the top of the vice president’s list of international priorities. However, what struck many as surprising was the cold reception that America’s most prominent Christian Zionist politician received during his January visit, not only from Christians in the Holy Land but those across the region as well. It is essential for any concerned about the welfare of Middle Eastern Christians to understand why an administration that has placed the defense of Christians in the Middle East among its foreign policy objectives has drawn the ire of the very people they claim to be protecting.

When Pence announced his intention to visit the Middle East, he said meeting with Christian leaders in the region was a top priority. However, President Trump’s December 2017 decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel triggered a predictable (though, apparently, unanticipated) backlash from Christians across the region.

Following the announcement, the patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt, Tawadros II, declined the vice president’s invitation to meet during his four-day visit—the Coptic pope rejected one of the most openly Christian vice presidents in recent history. This was followed by similar reactions from Christian clergy in Bethlehem. Also notably absent from the final itinerary was a visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem after the church’s custodian of the keys refused to be present at the event. Consequently, the trip was limited to meetings with Israeli politicians and visits to Jewish holy sites. Pence did not meet with a single indigenous Christian leader in the Holy Land.

A history of violence

When the United Nations in 1947 originally proposed creating the states of Israel and Palestine out of the territory that had previously been under British custodianship, it set aside Jerusalem to be an international city. But in the aftermath of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Jerusalem was divided between Israel and Jordan. East Jerusalem—home to the Old City and its Holy Sites—remained under Jordanian rule until the Israelis occupied the West Bank during the Six Day War of 1967.

Under international law, territory gained by a country during a war can only remain occupied until a final peace agreement between the belligerent nations settles its final status. In the meantime, nothing can be done to alter the demography of the area in dispute.

Israel, however, proceeded in 1967 to unify the municipal governments of East and West Jerusalem. This was followed by formal annexation in 1980. Since 1967, Israeli settlements have grown up in East Jerusalem, changing the demographic character of the city. In the current political climate, it is impossible to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel without also lending legitimacy to Israel’s contentious policies in the portion of the city occupied since 1967. This, in turn, exacerbates tensions between Israelis and Palestinians.

But while the threat of violence is detrimental to everyone in Jerusalem, how does legitimizing Israel’s unilateral actions specifically harm Christians in the city?

Breaching the status quo

While international law speaks of preserving the demographic status quo of areas under military occupation, Christians in Jerusalem speak of a different kind of status quo—one that exists between the city’s religious groups. The religious status quo is not a single legal document but a collection of traditions, treaties, and informal agreements dating back to the 18th century that helps maintain the delicate balance of power that has existed in the sharing of the Holy Sites of Jerusalem—the first status quo decree dates from the reign of Ottoman Sultan Osman III in 1757. Since the fall of the Ottoman Empire, all subsequent governing authorities in Jerusalem—including the British (1917-1948), the Jordanians (1948-1967), and the Israelis (1967-present)—have all affirmed the status quo as legally binding.

Taken together, the status quo agreements guarantee each religious group access to their holy sites by placing a freeze on their property holdings in perpetuity from the time of the agreement. In other words, as a result of the status quo, no religious group in Jerusalem should ever have to fear the expansion of any other group to their detriment.

However, following the Israeli annexation of the Old City, Christians have repeatedly raised the alarm that the status quo is in jeopardy. In 2017, the Patriarchs and Heads of Churches in Jerusalem issued three letters identifying the crisis of the shifting status quo. They wrote, “We see in these actions a systematic attempt to undermine the integrity of the Holy City of Jerusalem and the Holy Land, and to weaken the Christian presence.”

Former Ambassador Patrick N. Theros, representative to the U.S. of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, said these challenges to the status quo pose “an existential threat to Christian Churches in the Holy Land.” Speaking about the effect on churches, Theros said, “Some actions are motivated by politics while others appear purely mercenary in character. Each action targets church properties, properties without whose revenue no church in the Holy Land can maintain the most important Holy Sites in the world.”

Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem has allowed groups of radical nationalists, such as Ateret Cohanim, to settle there. Unlike most Israelis, these settler groups are not content with the current Jewish presence in Jerusalem and are intent upon making Jerusalem an exclusively Jewish city through land acquisition. Their U.S.-based affiliate calls on its website for “a united Jerusalem that belongs solely to the Jewish people.” Stephen Colecchi, director of the International Justice and Peace office of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, recalled a visit earlier this year by a delegation of Catholic bishops. “I found myself walking through the Old City of Jerusalem with Catholic clergy,” said Colecchi, and the visiting religious leaders were “literally spat upon by settlers who openly showed contempt for their Christian presence.”

‘Hell on Earth’

President Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel comes within the context of the threatened status quo. Last year, the Patriarchs and Heads of Churches in Jerusalem called attention to three key developments that represent a concerted effort to gradually make it more difficult for the church to maintain its property holdings. The first is a legal dispute between the Greek Orthodox Church and Ateret Cohanim, which had bribed an official of the patriarchate. A real estate transaction transpired between the settler organization and church officials who, according to the patriarch, were not authorized to act in the matter. The decision rendered by a Court of First Instance gave legal validation to these secret land deals, setting a frightening precedent in the eyes of many Palestinian Christians. The decision has been appealed to the Israeli Supreme Court.

The second is a proposed piece of legislation that authorizes Israel to retroactively seize any lands on which church rights have been transferred to private investors. If this bill passes the Knesset, church leaders fear that it will result in significant state appropriations of church lands.

Most recently, however, the city of Jerusalem’s decision (which is currently suspended) to tax church properties that are not exclusively used for worship poses an even greater challenge to the churches’ already strained financial resources. The taxes would be applied to any property that is not actual worship space. These taxes are problematic for church-related properties and could constitute a double tax for the commercial properties whose lessees already pay these taxes to the city of Jerusalem.

Under these circumstances, the Trump administration’s action signals that the United States is willing to turn a blind eye to these developments and their potentially devastating effects on local churches in Jerusalem. Charlie Abou Saada, a Palestinian Christian from Beit Sahour near Bethlehem who has a doctorate in Vatican law, said: “Churches of the Holy Land have always taken a stand for justice and equality, and all in a peaceful way.” He worries about the long-term effects of Trump’s action. “This provocative act will negatively affect the presence and the future of Christianity here,” he said. “Christians are the salt of this land. We are peacemakers. ... If [Christians were ever to] vanish, the Middle East will be hell on the Earth.”

If Palestinian Christians believe that the president’s action reflects a broader American apathy toward the erosion of religious pluralism in Jerusalem, what can U.S. Christians do to prove otherwise? One of the easiest places to start is by changing the way we visit the Holy Land. Rather than focusing solely on the historical significance of the land for Christianity, we can also make meeting with and listening to Christians who live there now a central part of the experience.

Local Christians often issue an invitation for visiting pilgrims to not only see the dead stones of the Holy Land, but also to visit the “living stones”—Christians who have been living in the land since the time of Pentecost (Acts 2). Sharing these experiences with our families, friends, and neighbors is critical for raising awareness among the American general public.

By gaining a better understanding of the consequences of our elected officials’ actions, we can all work to advocate for a U.S. foreign policy that does not endanger either the chances for a just peace in the region or the multireligious character of Jerusalem. Such a policy is vital for ensuring vibrant faith communities—not only for Christians, but also for the hundreds of thousands of Jews and Muslims who also call the Holy City their home.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!