Feature

AMERICAN HYPERPOLICING and mass incarceration are products of 50 years of cynical politics, vicious economics, and unconscionable racism—as the mass uprising in the wake of George Floyd’s killing has brought into ever clearer focus. Across the country, organizers on the ground are pushing to defund the police. Meanwhile, for people Left, Right, and center, “ending mass incarceration” has become a standard political talking point. But what precisely would “ending mass incarceration” entail?

Imagine that tomorrow we were to enact the most radical reforms to the prison system conceivable—reforms tailored to mass incarceration’s political, economic, and racial dimensions. First, to scale down the war on drugs, we could pardon every person in state and federal custody who is incarcerated solely on the basis of a nonviolent drug offense. Second, to stop caging people simply because they are poor, we could release every pretrial defendant who is sitting in jail solely because they are unable to make bail. Third, to end what’s been called the New Jim Crow, imagine if every Black state and federal prisoner—who constitute one-third of those in prison—were freed, regardless of whether they were guilty of a crime. By committing to these three measures (which, needless to say, aren’t being seriously considered in Washington or in any state capital), the U.S. would reduce its prison population by more than 50 percent, to a tick over 1 million people. In the COVID-era especially, when prisons and jails are incubators of the virus, many lives would be saved. Families would be reunited. Much suffering would be forestalled.

What such a robust menu of reforms would not meaningfully do, however, is end mass incarceration. Even at half its current size, the U.S. incarceration rate would remain three times that of France, four times that of Germany, and similar degrees in excess of where it was for the first three-quarters of the 20th century. Given the massiveness of the American carceral edifice, we cannot reform our way out of mass incarceration. Nor does the reformist impulse address the crux of the problem.

A FEW YEARS ago, an acquaintance and I found ourselves debating the value of art in a capitalist society—a suitably light topic for a summer evening. My companion believed strongly that art must explicitly denounce the world’s injustices, and if it did not, it was reinforcing exploitative systems. I, ever the aesthete, found this stance reasonably sound from a moral perspective but incredibly dubious otherwise.

Then, as now, I consider art’s greatest function to be its capacity for expanding our conceptions of reality, not simply acting as moralistic propaganda. After all, the foundational thing you learn in art history is that the first artists were mystics, healers, and spiritual interlocutors—not politicians.

We started making art, it seems, to cross the border between our world and one beyond. Prehistoric wall paintings of cows and lumpy carvings of fertility goddesses serve as the earliest indications of our species’ artistic inclinations, blurring the lines between religious ritual and art object. Even as the world crumbles around us, I am convinced we must hold onto art’s spiritual properties rather than succumbing to the allure of work that only addresses our current systems.

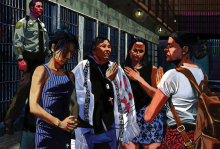

NONVIOLENT PEACEFORCE is an international nonprofit that works with communities facing violence to implement nonviolent strategies to help keep them safe. They have worked with communities around the world, including in Sri Lanka, Iraq, South Sudan, and Guatemala. Mel Duncan, Rosemary Kabaki, and Jessica Skelly of Nonviolent Peaceforce spoke in mid-September with Sojourners’ Betsy Shirley about their newest project location: the United States.

Sojourners: Why did you start projects here in the U.S. this fall?

Mel Duncan: We recognize that right now there are many indicators of looming violence, whether it be strife over police brutality and racism, or the chaos that is being stirred up around the election, or the catastrophic experiences we’re seeing with climate change—all of these can trigger violence.

What risks do you see?

Jessica Skelly: As we look toward the elections and beyond, we can see some indicators for flashpoints of violence—election tampering, delays in the election, perhaps continued police brutality, instigation by agents provocateurs—and people want to know how they can mobilize in responsible and constructive ways and help de-escalate some of that violence and protect themselves.

1. Get involved

Scenario: Voting places are closed, and mail-in ballots are restricted because there are too few election workers due to COVID-19 concerns.

Tip: Democracy is a team sport. Everyone can be an election worker. Commit a certain number of people from your church to register as poll workers and mobilize medical personnel to speak on coronavirus-safe voting practices. The U.S. Election Assistance Commission hosts a video explainer and training information for each state, and you can support efforts to recruit young poll workers through powerthepolls.org.

“WHITE CHRISTIANITY IN America was born in heresy.”

This statement was made by Yale University theologian Eboni Marshall Turman last year before a large gathering of religion scholars. Marshall Turman, a formidable leader in African American theology, did not explain her meaning. In that room, she did not need to do so.

But as I heard her, I thought dolefully about how very long it took me as a white American Christian ethicist to be ready to engage or even to understand such a statement. I wondered doubtfully how many white American Christians today would be prepared to discuss it rationally. After all, part of what is so deeply wrong with white evangelicalism has to do with race. If what comes “after evangelicalism” does not address our racism at its roots, we shouldn’t bother.

To say that white Christianity in America was born in heresy is to make a theological statement about racism prior to any moral evaluation. It is to suggest that our local racism problem is ultimately rooted in heresy, a violation of central tenets of Christian doctrine. It is also to say that this heresy was present from the birth of American Christianity. There was no original innocence—the heresy and its resulting sins were there from the beginning.

This begs the question of whether the ultimate historical source of such heresy can be identified. It seems to me that a compelling starting point is 15th century Europe as it began conquering and colonizing the world in the name of Christ. The story begins with those first imperial powers, Spain and Portugal, but soon after extends to Britain and other European colonial nations, including Holland, France, Belgium, and so on. These were empire-building nations on the cusp of their grand adventures. They confidently believed themselves to be the center of the world, superior to all other cultures, entitled to conquer and colonize, and in doing so actively advancing God’s will. The European powers believed this for many centuries. Some would say that they, and their descendants, believe it still.

EACH SPRING, I plan how to survive the summer. Without the school-year routine, our family leans on relatives, friends, summer camps, and cobbled-together vacation time to get our kids through. But this year, everything stopped: In a pandemic, you can’t visit Grandma or drop off the toddler for a playdate. If raising children takes a village, our village has been scattered. And while the nation collectively experiences this ongoing trauma, parents are attempting to shepherd our children through the same.

A large part of parenting is risk assessment—a constant cost-benefit analysis of how the decisions you make will affect your children for the rest of their lives. When I was pregnant with my third child, now 1, I read Emily Oster’s Cribsheet: A Data-Driven Guide to Better, More Relaxed Parenting, from Birth to Preschool to alleviate the added anxiety. Oster, an economics professor at Brown University, correctly observes that with constantly changing internet recommendations on everything from breastfeeding to screen time, “there is reassurance in seeing the numbers for yourself.” She lays out the scientific data so parents can make informed decisions; for me, it offered confidence—and a rare sense of control.

But that sense of security goes out the window in a pandemic, unforeseen economic collapse, and necessary reordering of our institutional constants. Parents face new risks with precious little, and everchanging, data to guide our analysis. The most common fear shared by parents I’ve spoken to is that our kids won’t be OK—that in trying to find the balance between naked truthfulness and parental protectionism, we’ll lean too heavily to one side, that the wrong decisions will leave lasting marks that follow them into adulthood.

“I don’t know what the world is going to look like. Will I have the wisdom and the capacity and the ability to help guide her through?” Susi McCrea tells me. When we spoke, McCrea was 32 weeks pregnant and living in northeast Washington, D.C., with her husband, Christopher, who was recently laid off, and 1-year-old daughter Katja.

“Will we be able to help [Katja] build the resilience that she needs for something that’s so full of uncertainty—and maybe just a really uncertain world for quite some time—without instilling a lot of fear?”

WHEN THE U.S. Catholic bishops gathered to draft a document on race in the wake of the 2017 white terrorist rally in Charlottesville, Va., Bishop Anthony Taylor of Little Rock, Ark., submitted an amendment to condemn the imagery of swastikas, Confederate flags, and nooses. The U.S. bishops deliberated and voted to reject it.

The document, “Open Wide Our Hearts,” was billed as “a pastoral letter against racism,” making its writers’ inability to adopt the amendment condemning three famously extreme symbols of racism a curious one.The bishops explained themselves by arguing that swastikas and nooses were already “widely recognized signs of hatred,” which would seem to make them all the easier to condemn. (Interestingly, they eschewed this logic when issuing their only condemnation, against violence toward police.) As for the Confederate flag, “some still claim it as a sign of heritage,” they argued.

While this logic indefensibly hand-waves the history of slavery, murderous opposition to civil rights, and violence such as the 2015 shooting at a Black church in Charleston, S.C., as a vaguely benign “heritage,” it also fails to account for the flag’s use among those with no ties to the Confederacy. Take, for example, U.S. Rep. Steve King. While most widely known for asking what’s so wrong with white supremacy and white nationalism, King, who is Catholic, has also displayed a Confederate flag on his congressional desk. The quite obvious meaning of the flag’s presence on the desk of King, who represents a district in Iowa until January, is apparently lost on the bishops, given their claims about “Southern” heritage.

The decision to avoid condemning swastikas, nooses, and Confederate flags would be troubling under any circumstances. But this moral failure is compounded by the fact that Catholics are among the most integral groups that rally behind these symbols. From the highest reaches of government to the lowest depths of social media, many members of hate groups and politicians who model their talking points are part of the bishops’ flock. Catholics not only contributed to the platform for the so-called alt-righters who terrorized Charlottesville and killed Heather Heyer but are leaders and even founders of the most dangerous neo-Nazi groups in existence.

The Catholic Church, once persecuted by the Ku Klux Klan, today has a visible white-power faction. As long as the bishops actively refuse to condemn its banners, they give white supremacists space to embrace their anti-Black and anti-Semitic work free of religious dissonance.

CONSCIENCE, REMARKED MORAL theologian Richard Gula, “is another word like ‘sin’—often used but little understood.”

As a teenager growing up in the naval stronghold of San Diego during the Reagan era, I experienced a recurring nightmare about war with the Soviet Union, which became darker as I learned more about the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which took place 75 years ago this August. During that time Joan Kroc, an anti-nuclear leader who was also principal owner of the San Diego Padres baseball team, and others organized Mothers Embracing Nuclear Disarmament. On the 40th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, thousands gathered in Balboa Park, and my fear was transformed into a conviction of conscience to work for nuclear disarmament.

Conscience involves the capacity to discern and choose the morally right course of action in a particular situation. In doing so, a person brings to bear a lifelong process of formation of conscience. Each person has the obligation to form his or her conscience as fully as possible, and to follow it.

The formation of conscience is highly personal and socially situated. Hebrew and Christian scriptures, as well as theological writings such as those by St. Augustine, provide steps for building moral character, teaching moral reasoning, and forming our moral conscience to offer judgment based in practical reason to recognize and seek what is good and to reject what is evil.

This process for engaging Christian moral thinking involves four key elements:

- Be open to the truth and draw upon the prudent wisdom of personal and communal experience.

- Seek reliable teaching, including from scripture and Christian tradition.

- Review the best available information and consult trusted persons with relevant expertise.

- Engage prayerful discernment and conscientious action through the gift of the Holy Spirit to guide one’s application of moral values in each case.

AFTER CARMEN AND her son, William, were set on fire by gang members and then rescued by a passerby, they fled El Salvador to seek refuge in the United States. In a caravan headed north through Mexico, by chance they met five family members: Carmen’s sister, Cecilia; Cecilia’s husband, Oscar; and the couple’s three teenage children—twin daughters and a son.

When they reached the end of their 2,800-mile trek to the U.S. border outside Tijuana, Mexico, the entire family surrendered to U.S. immigration officials.

That’s where, in November 2018, they met Monica Curca, founder and director of Activate Labs, a nonprofit organization focused on peacebuilding and human-centered “peace design.” The family members (surnames withheld for their safety) were among 30 immigrants for whom Curca’s organization provided advocacy and accompaniment and arranged financial sponsorship upon their entry into the U.S.

Once in the immigration system, the men and women were separated and sent to federal detention centers in Arizona and California; the men were detained for eight months and the women for five. William was separated from the family entirely, Curca explained. He ended up detained in Ferriday, La., in the former River Correctional Facility, a prison converted into an immigration detention center. Having been left for dead in El Salvador, he could have qualified for asylum—a form of legal protection for refugees who fear persecution in their native countries. But the activists working with him could not procure a lawyer, said Curca, and he was so miserable he chose deportation rather than prolong the suffering.

MEN OF POWER have always abused that power. Every woman knows it, which is why none of us were surprised when #MeToo came for the church. But we weren’t prepared for Jean Vanier.

The details of Vanier’s story are well known by now, but they bear repeating. Vanier, who died in May 2019 at the age of 90, was the internationally celebrated co-founder of L’Arche, a global network of homes where people with and without intellectual disabilities live together in community. A Roman Catholic layperson who never married, Vanier was regarded by many as a living saint; his New York Times obituary hailed him as “Savior of People on the Margins.” His writings on spirituality and community were best sellers and universally revered as modern classics.

Vanier was also a sexual predator. A report following a posthumous investigation by L’Arche International, the organization that Vanier founded, revealed that he sexually abused at least six women in his spiritual care between 1970 and 2005. These six cases are the ones we know about. The women, none of whom knew each other, offered remarkably similar accounts of Vanier’s strategy of sexual predation within the context of spiritual direction.

L’Arche’s summary report is excruciating to read, because it reveals a pattern of manipulation and exploitation shot through Vanier’s role as a spiritual director. “He told me that this was part of the [spiritual] accompaniment,” one survivor reported. Even as she told him she was struggling to “distinguish what was right and what was wrong,” he pushed on, offering bizarre scriptural warrant from the Song of Solomon and—perhaps most chillingly—his contention that in their sexual interaction, “This is not us, this is Mary and Jesus.”

“WHAT'S YOUR CASTE, Daniel?”

Glancing around my sixth-grade history classroom, I knew my answer to the teacher’s question wouldn’t mean anything to my American peers. It hardly meant anything to me, a South Asian kid. As years passed, I heard murmurs about controversy surrounding the teaching of the Hindu caste system in our classrooms. And in 2017, I watched California’s board of education vote to approve history textbooks that erased key aspects of a 3,000-year-old system of apartheid that presently affects almost 2 billion people around the world.

Caste is personal, systemic, violent, and subtle—all at once. Dalits, caste-oppressed people formerly known as “untouchables,” know this too well. As Dalit theologian and Christian minister Dr. Sunder John Boopalan told me, caste is the “oldest surviving form of anti-human oppression.”

How does caste work? Why does it matter? What do we do about it?

The best teachers on this subject are those who have persisted, resisted, and found God amid the brunt of caste oppression. Dalit liberation theology exists as a beacon of hope against crushing evil, calling all of humanity to see God, freedom, and ourselves in a renewed way.

Caste as an Origin Story

IN A 2016 INTERVIEW, civil rights activist Ruby Sales said that every theology should have “hindsight, insight, and foresight.” Using hindsight, we often find that oppression is rooted in the origin stories we tell.

The origin story of caste goes back to the ancient roots of Hinduism—more accurately called Brahminism—honed over centuries by upper-casts groups seeking to maintain social and political power and further entrenched by British colonial forces. The creation story in the Purusha Sukta tells of a primeval god sacrificing himself to create the world. Varnas, or castes, emerge from different parts of his body. Brahmins (priests and scholars) originate from his head, Kshatriyas (warriors and administrators) from his arms, Vaishyas (farmers and merchants) from his thighs, and Shudras (laborers and servants) from his feet. This hierarchical system ranks people according to purity and assigns their occupations.

EVERY DAY, BEFORE the coronavirus had us sheltering in place, I drove by a Confederate monument on the state capitol grounds near my home in Raleigh, N.C. It was unveiled in 1895 by the granddaughter of Stonewall Jackson, Julia Jackson Christian. Its 75-foot-tall granite column is a fixture of the landscape as people walk past on their way to work or sit on benches beneath its shadow, the shaft marked with the words “to our Confederate dead.”

The monument is strategically placed to assure maximum visibility. Everything about it is purposeful and planned. It makes a claim on the space—claiming the ground, the air, the power of public land with a particular version of history.

“To our confederate dead.” But the question that burns on the stone: Who does “our” represent?

Injustice, idolatry, and repentance

IN 2019, CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va., was still reeling from the August 2017 Unite the Right weekend during which counterprotester Heather Heyer was killed by a white nationalist. Two local Methodist pastors—Rev. Isaac Collins and Rev. Phil Woodson—decided to gather community members for a weekly Bible study aimed at reinterpreting the Confederate monuments that mark Charlottesville’s public space. They called it “Swords into Plowshares: What the Bible says about injustice, idolatry, and repentance.”

The inspiration came from Jalane Schmidt, a public historian and religious studies professor at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, who has co-led truth-telling tours of the monuments since 2018. Schmidt suggested Collins take up the work of theological interrogation of the history embedded in these monuments and how this history lives on in the churches and Christians in their city.

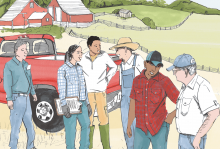

IT WAS COLD — even for northwest Iowa in November. And I was late.

I thought I could make up time if I took the back way, a route I’d driven many times before. But the one-lane bridge across the Rock River was out and, judging by the abandoned construction site, it hadn’t been open for a while. I had moved away four years earlier and was a little behind on local traffic patterns.

To locals, the region surrounding the Big Sioux River drainage basin—stretching across parts of Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Minnesota—is known as “Siouxland.” To most Americans, this is flyover country.

I grew up in Siouxland, crisscrossing the region for family gatherings, 4-H horse shows, and trail rides, but I knew my time there was limited. Through TV, I learned about life in the big city and what the rest of the country thought of hicks, hillbillies, and hayseeds like me. I learned that to be successful, I had to leave. And so, like many of my classmates, I left as soon as I could.

I went to college in Minneapolis and pursued a career in media; after graduation I spent time in Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C., working on shows such as Monday Night Football and Good Morning America.

But on the morning of May 12, 2008, everything changed: Hundreds of federal agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement raided an Iowa meatpacking plant, arresting 389 community members. At the time, I was a media producer for Sojourners, so I traveled to Iowa to cover the humanitarian response organized by Sister Mary McCauley, parish administrator of the local Catholic church.

Within hours of the raid, Sister McCauley had the entire community of 2,269 residents organized. When I interviewed her a few days later, the church was full of children still waiting to be reunited with their families. The church’s fellowship hall was filled with clothes, meals, and supplies for the children; community volunteers worked through legal paperwork on behalf of those detained. In a moment of complete chaos, community members rose to the challenge and stood together with their neighbors. It was at this point I realized the power of rural organizing. I was hooked.

Leveraging the gifts of the community

IN MARCH, AS the pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus erupted around the world, rural hospitals in the U.S. faced a particularly grim reality: Like hospitals across the nation, they faced a shortage of personal protective equipment such as N-95 masks and gowns. But unlike their urban and suburban counterparts, rural hospitals were already struggling. According to a 2017 study, 41 percent of rural hospitals operate at a loss, a result of decreasing Medicare reimbursements, more patients with underlying conditions, and fewer patients with private insurance. “We’re stretched thin as it is,” one hospital CEO told the Washington Post. “We’ll improvise and make it work however we can.”

As cases of COVID-19 skyrocketed, I thought about McCauley and all the organizers like her that I’ve met in the 12 years since the Postville immigration raid. Many of the best community organizers I know would never give themselves that title. They don’t work for a campaign or an organization. Often, they’re just everyday folks who believe their community is worth fighting for.

LAST YEAR I went on my first cruise. Joined by my favorite kinfolk, I caught up on my rest, sampled craft beer, and enjoyed some really great food. As the boat made its way to the Caribbean and Cayman Islands, I attended a performance by Delta Rae, a rock and folk band with Southern roots and a flair for storytelling. I was moved by many of the songs they performed that night, but it was their song “Hands Dirty” that stayed with me long after we disembarked.

The song gives voice to a woman who, like many in the service industry, works hard but doesn’t catch a break. In the chorus, vocalists Brittany Hölljes and Liz Hopkins sing:

I get my hands dirty

I show up so early

They show me no mercy

So I just keep working

Maybe God could save me

In this song I heard someone whose work had never been recognized. I heard echoes of all the ways our society has continually undervalued women’s labor—especially the labor of women of color, who are disproportionately marginalized in the workforce. Yet even as this woman experienced the sharp end of capitalism’s stick, the song made it clear she wasn’t giving up; she was going to keep working, imagining the future could be different. And as I listened, I thought: Isn’t that our work right now—to get our hands dirty? To imagine a different way of being and becoming, take a leap of faith, dig deep, and roll up our sleeves? And, if that is our work, do we have the courage to do it?

I AM TERRIFIED of tripping. Thanks to a couple memorable tumbles over the years—the most recent of which involved a face-plant while on a run—I always double-knot my shoelaces and look down at my feet when I walk. Remaining steady and stable is always in the back of my mind.

But on a trip to Berlin in 2017, I found myself repeatedly tripping over something in the ground. The source of my stumbling, I soon learned, were Stolpersteine, which translates literally to “stumbling stones,” or more metaphorically, “stumbling blocks.” Stolpersteine are cobblestone-sized bronze plaques embedded in streets and sidewalks throughout Europe, each slightly raised above ground level and engraved with the name and life dates of a Holocaust victim, including murdered Jews, members of the LGBTQ+ community, Sinti and Roma people, people with physical or intellectual disabilities, and other ethnic and political minorities.

These commemorative stones are part of an ongoing art project, installed at the last place each person lived or worked before falling victim to Nazi crimes. Above each engraved name are the words “hier wohnte,” or “here lived,” serving as a reminder that this person did not build their life just anywhere, but right here. Each day they walked on this ground.

Each is unique

THE IDEA FOR Stolpersteine began in 1991, when artist Gunter Demnig painted a white line through the streets of Cologne to trace the deportation of 1,000 Sinti and Roma who were forced out of the city just 50 years prior. “An old lady stopped by and scolded my work, insisting there had never been any Gypsies in Cologne,” said Demnig. Her denial prompted Demnig to find a way to more permanently preserve the memory of those killed in the Holocaust.

HOME. PERPETUAL WANDERING is a crucial aspect of the Christian narrative. Cast from Eden, Christians are forever strangers in a strange land.

But for black and Indigenous people, that means something very different. If the original sin of the colonized West is genocide and slavery, that is not our sin. And yet it rendered us homeless as surely as the apple in the Hebrew narrative. Forcibly uprooted again and again, black and Indigenous people seek to create, and return, home.

Indigenous scholars such as Kim TallBear and Kim Anderson have described the power that the American idea of home has on the minds of people and politics, and the threat posed to that ideal by Indigenous families who did not live in nuclear relationships with women in a subordinate role. Historically, land allotments for settlers seeking to homestead or for Indigenous people were allotted to heads of households based on the size of households; having a wife and children ensured a larger allotment. Indigenous people who were determined to be more than “half-blood” were not given land outright but had their allotment held in reserve because they were not considered capable of managing the land themselves.

The founders of the United States and generations of subsequent legislators defined the home in narrow and specific terms, creating laws and policies that ensured that free blacks, Indigenous people, immigrants, and poor whites were unable to achieve this American Dream. Vagrancy laws separated families and jailed people under vague and arbitrarily written codes. The Homestead Act, while providing land for settler families, required clearing the West of the people living there. People were framed as “nomadic” in order to justify the theft. The practice of redlining, marking boundaries around primarily black neighborhoods, was used to deny mortgages and exclude black families from home ownership.

The homeless, whatever their stories, are still viewed as suspect by Western society. People whose sexuality does not conform to the American ideal have long been described as threats to marriage and family, and many landlords rely on their Christian beliefs to justify denying homes to LGBTQ people. Yet around the world, U.S. media promotes a glowing image of the American home and family—making promises the country refuses to keep.

The church’s role

SO IT'S A strange dissonance in church, singing songs about wandering and seeking a home when, as an Indigenous woman, my homelessness is because of the church’s role in empire and colonization. This was not just complicity, but active engagement, directing the process and benefiting from the displacement and forcible relocation of black and Indigenous people, as well as from foreign wars that destabilize other countries and generate refugees and asylum seekers.

It was a pope who wrote the so-called Doctrine of Discovery, giving colonizers rights over our land; Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg cited it to deny an Oneida land claim in 2005. It was the churches who ran residential schools and whose missionaries paved, and continue to pave, the way for capitalism and colonial government by marketing the constructed idea of home as a Christian ideal and model.

IN 1985, WHEN Jesse Milan Jr. was in his late 20s, no one from his Philadelphia church attended his partner’s funeral. Not because they refused, but because Milan didn’t invite them. Doing so would have required him to say what he felt uncomfortable sharing: He loved a man who had HIV. He is a man who has HIV.

“This is never going to happen to me again,” Milan vowed to himself at the funeral, regarding the loneliness he felt because he didn’t draw close his church family at one of the most painful moments of his life.

Milan is now the president and CEO of AIDS United, an organization fighting the HIV epidemic in the U.S. He is adamant that no one in the HIV community be isolated from the love and support they need. “People living with HIV,” said Milan, “have a longing to belong. A longing to be cared for and a longing to not be silent or secret.”

A lifelong Episcopalian, Milan grew up in a congregation in the Diocese of Kansas, following the example of his mother and father in serving their spiritual home and, in times of need, allowing their siblings in Christ to serve them. Milan kept this mutuality in mind when he enrolled at Princeton University and, struggling to transition from public school and homesick for his church, joined the Episcopal Church at Princeton. It was, Milan told Sojourners, “an anchor, a port to tap into on a regular basis whenever I needed it.”

Helping communities live

FOR MANY PEOPLE today, the closest we get to understanding the impact of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and early ’90s is through stage and screen portrayals such as Pose, Angels in America, and Rent. For others, the memories and losses of that time are vivid and unforgettable.

For instance, Jesse Peel, a gay psychiatrist and community organizer, documented in his journals the avoidance and terror of HIV that overtook his home city, Atlanta, and the nation. As many people rapidly contracted and died of the disease, doctors struggled to understand what was happening and many nurses refused to bring meals into the hospital rooms of the stricken, Peel wrote in documents he donated to a collection at Emory University. By 1994, AIDS was the leading cause of death for Americans age 25 to 44. It killed more than 350,000 people in the country between 1981 and 1995.

“I think the experience of people who are of a certain age will always be colored by our experience of the death and the dying,” said Milan. “Today, I sense that [younger] people’s commitment to HIV/AIDS work is more about the rights and the inequalities that are manifested in HIV and AIDS. They have a broad lens about where human rights need to advance, and that broad lens includes the trans community and all others.”

In the early years of the epidemic, many pastors and religious people publicly denounced and turned their backs on HIV-positive people. Others embraced those who were suffering, opening care programs and advocating for government funding. Reminding the nation’s leaders of their responsibility to the HIV community is a job that’s been done by many Christians and is a significant part of AIDS United’s history and present work.

AMID THE NOISE of our news cycles, there are the occasional stories that become part of our personal journeys. Sometimes, we only need a word or phrase to bring them back with full force, like “the Holocaust” or “9/11.” Sometimes, it’s just the name of a city. Pittsburgh. El Paso.

For me, Pittsburgh now conjures up images of a deliberate slaughter of Jews in their synagogue because of their religion—which is also my religion. According to their attacker, it was also because they supported the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, which resettles refugees, including people from Africa, Eurasia, Latin America, and the Middle East.

Similarly, El Paso reminds me of my grandmother. She was an immigrant who escaped her Jewish village after her left arm was badly burned—and forever scarred—during a Cossack attack. In El Paso, Hispanic immigrants were also deliberate targets, as another mass murderer went to Walmart.

Each of these tragic events is personal for me, and each is horrifying in its own right. But they are not isolated phenomena. The anti-Semitic and anti-immigrant sentiments on which they were built are intertwined.

Both reflect long-standing tribalism rooted in hate, and both are being exacerbated by rapid societal change, globalization, and emerging transnational networks proliferating white supremacist ideologies. These realities give us Pittsburgh, El Paso, Jersey City, Poway, and countless other mass murders—while exponentially metastasizing hate, the dehumanization of “others,” and violence.

Intertwined xenophobia

ANTI-SEMITISM AND XENOPHOBIA have existed throughout history and, most certainly, throughout the American experience. Grounded in dehumanizing stereotypes and malicious conspiracy theories, anti-Semitism operated alongside xenophobic mindsets that forced Jews into ghettos or sought to push them out of communities altogether, as the unwelcome stranger.

Similarly, immigrants to the U.S. and migrants worldwide have repeatedly been othered and ostracized, often prevented from freely following their faiths and being viewed as lesser than those in so-called civilized society. Consider the Irish who emigrated during the potato famine. As immigrant Catholics they faced violence and the emergence of anti-immigrant groups dedicated to “returning” the country to their homogeneous vision of the U.S.—such as the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, which was committed to preserving a Protestant America. In a similar way that Jews have historically been labeled, the Irish were stereotyped as undesirable and dangerous. Today, we hear the same drumbeat, this time toward Muslims and other groups seeking to emigrate across borders, people who are called invaders and terrorists.

WE GATHERED THIS fall on the steps of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church. Summoned by the Detroit chapter of Black Youth Project 100, we were preparing to march a mile-long stretch of gentrified Michigan Avenue, which intersects there. I had served the church for 11 years as pastor, and in the last dozen or so this Catholic Worker neighborhood had been invaded by $400,000 condos, plus destination bars and restaurants. Among others, guests at our Manna Meal soup kitchen and Kelly’s Mission, largely black, are stigmatized and made unwelcome.

But the focus of the march was more than the gentrified influx: Accompanying gentrification has been a heavy increase in electronic surveillance by the so-called Project Green Light, where businesses pay for street cameras that feed to a Real Time Crime Center deep in police headquarters. In areas like this, as with downtown, high surveillance makes white people feel safe for moving in or just shopping and dining.

Dan Gilbert, a mortgage, finance, and development billionaire, owns more than 100 buildings downtown, all covered with the cameras of his own Rock Security. They feed to his corporate center, but also to the police crime center. Detroit Public Schools has its own central command, which is not yet tied to the police center. Likewise, a separate system of streetlight cameras, and even drones, is under development. California recently banned the use of facial recognition software in police body cams, which would convert an instrument of police accountability into a device of surveillance. Michigan has not.

Most Project Green Light cameras are in Detroit neighborhoods, on gas stations, bars, party stores, churches, and clinics. There, each is marked with the constant flash of green lights that say: You are being watched. When the city demolished a house behind ours, we had to hang light-impervious curtains to prevent green pulsing on our bedroom wall from the funeral home a block away.

For nearly two years, unacknowledged, facial recognition software was being employed by the police department. The software can be used with a “watch list” of persons of interest, plus access mug shots, driver’s license and state ID photos, and more—perhaps 40 million Michigan likenesses. A string of recent studies indicates the software can be inaccurate for dark-skinned people, creating false matches and prosecutions. A federal study released in December, according to The Washington Post, showed that “Asian and African American people were up to 100 times more likely to be misidentified than white men.” Thus, resistance to the system quickly mounted in Detroit, which is 80 percent black.

There are two surveillance-industrial complexes. It’s said the days are coming when nations will need to choose which surveillance network to join, the American or the Chinese version—parallel to military alliances. China has 200 million cameras focused on its people, but with 50 million, the U.S. has more cameras per capita. The best facial recognition technology is coming out of Chinese firms, but these are banned in the U.S. because of their connection to “human rights abuses.” The Detroit contract is with DataWorks Plus.

Orwell would be astonished

THE BLACK YOUTH PROJECT 100 march along Michigan Avenue was more like a dance parade, thick with drums, rhythm, and chant: “Black Out Green Light.” This stretch is a so-called Green Light Corridor, where all businesses participate, marked with modest and tastefully lighted signs. At each venue we passed—coffee house, bar, restaurant, bagel shop—three or four folks would go inside with signs and leaflets to chant and speak. A nonviolence training a couple weeks prior had prepared participants for the increasing police presence as the action proceeded. Squad cars blared sirens and officers stood by doorways, never blocking entrance, but threatening. Back at the church Rashad Buni of BYP100, which seeks “Black Liberation through a Queer Feminist Lens,” called for surveillance funds to be spent instead on neighborhood investment—foreclosure prevention, job training, clean affordable water—as the real source of community security. We all want safe neighborhoods. The question he puts is: By what means?

BEN WILDFLOWER IS a self-described “high-church lowlife.” He lives in Kensington, a Philadelphia neighborhood that’s also home to intravenous drug users and sex workers. Wildflower—the surname he and his wife adopted after their marriage—is white, bearded, and male; he grew up among conservative evangelicals but now attends an Episcopal church (“a wonderful, welcoming space for so many people alienated by the church,” he said, “but also a bizarre, bourgeois institution”). Sometimes he fixes his roommates’ bikes to cover rent; he aims to live on very little.

I came across Wildflower through his handmade religious prints that resemble the black-and-white woodcuts found in The Catholic Worker , albeit with a little more attitude: “O Mary conceived without white supremacy,” reads one of Wildflower’s prints featuring the Holy Mother using aerosol flamethrowers to destroy Confederate and Nazi symbols, “pray for us trying to dismantle this shit.”

Wildflower doesn’t love the word “anarchist” because it sounds too self-assured (“like how a super-duper Reformed person has answers for everything”) and often evokes scenes of white dudes eager to break stuff and punch cops. But he sticks with it: “I’m an anarchist because I oppose hierarchical power structures,” said Wildflower. “You apply it to sex and gender, you have ‘feminism.’ You apply it to white supremacy and racism, and you have ‘anti-racism.’ So what is it when you apply it to the modern state? I guess we don’t have a word better than ‘anarchism.’”

Does it bring joy?

IN THE PAST four years, it’s been tempting to believe the main problem with U.S. democracy is the current occupant of the White House and the electoral politics that paved his way to office. But Christian anarchists offer a different perspective.

“The thought of America crumbling should bring you joy,” Wildflower told me in an interview last spring. As Christian anarchists see it, the problems that exist in our nation—poverty, white supremacy, militarism, economic inequality, and on down the list—are not aberrations in an otherwise good system, but rather inescapable outcomes of any system where some people have been put in power over others. And as people of God, Christian anarchists feel called to dismantle these oppressive systems and create radical alternatives.

Take prisons: “I think people are valuable and shouldn’t be warehoused in cages,” said Wildflower. “I don’t think [prison] changes people; I don’t think it makes us safer; I think it’s a tool to control and impoverish communities of color. I want it to be destroyed.” Though he participates in what he calls “reformist” actions, such as voting for a better district attorney or advocating to change sentencing laws—something his younger anarchist self would have scoffed at, but that he felt was important after listening to women and people of color in his community—he doesn’t feel those actions will ever fix the underlying problem. “A system that holds people accountable for injustices looks so unimaginably different than the prison system, that I’m still totally on the ‘burn it down’ side.”