Feature

IN APRIL, Pope Francis made a long-awaited apology to a Canadian delegation of Inuit, First Nations, and Métis leaders at the Vatican for the “deplorable” violations children suffered at Catholic-run Indian Residential Schools for more than a century. The pope committed to come to Canada in late July to make his confession personally to residential school survivors and their descendants for “the abuse and disrespect for your identity, your culture, and even your spiritual values.”

In this historic apology, Pope Francis stated, “Clearly, the content of the faith cannot be transmitted in a way contrary to the faith itself.”

This watershed moment comes 25 years after Harry Lafond—a Catholic and then-chief of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan—raised issues of Indigenous faith and culture in a historic audience with Pope John Paul II during the Vatican’s 1997 Synod of the Americas. An educator and Catholic deacon, Lafond and his ancestors have a long history of building bridges between settler and Indigenous communities. J.B. Lafond, Harry’s great grandfather, was a spokesperson for Chief Keetoowayhow at the sixth of the 11 numbered treaties signed by First Nations with the Canadian Crown between 1871 and 1877. At the Treaty 6 table in 1876, J.B. Lafond negotiated with a British colonial government for relief from the flood of encroaching European settlers on the prairies. The parties were trying to avoid the violence waged against the Lakota, Dakota, and Cheyenne to their south. Though traditional Muskeg Lake Cree territory covered hundreds of square miles, Treaty 6 allotted a reserve of only 42 square miles.

Harry Lafond’s family has lived on the Treaty 6 reserve since then. He and eight of his 11 siblings attended nearby St. Michael’s (Duck Lake) Indian Residential School, run by the Roman Catholic Church.

In 1975, after marrying Germaine Laplante, a former Catholic sister of Métis (mixed European and Indigenous) heritage, Lafond worked as an educator and then served for a decade as chief at Muskeg Lake. Later, he directed the Office of the Treaty Commissioner of Saskatchewan, formed to bring Indigenous views of treaty covenants to the wider settler community. His tenure coincided with the years of Canada’s groundbreaking Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

In 2015, after six years of gathering testimony from across Canada, the TRC issued 94 calls to action to repair past and continuing damages wrought by the residential school system as an instrument of colonization. These included 10 calls directed toward churches, one of which demanded an apology from the pope on Canadian soil for abuses—which is being realized this summer, thanks to seeds planted by leaders such as Harry Lafond.

Today, Lafond continues to foster dialogue about what it means to be both Cree and Catholic. He works to renew Cree language and traditions among his people, while accompanying settlers interested in restorative solidarity. In May, the first federal study of Native American boarding schools in the U.S. identified more than 400 Indian Residential Schools and more than 50 associated burial sites. We interviewed Lafond in March and May 2022 by Zoom and email about his journey toward restorative justice and how the church might be replanted in Cree culture and land.—Elaine Enns and Ched Myers

Elaine Enns and Ched Myers: How did you feel when you heard Pope Francis’ apology in April to the First Nations delegation?

Harry Lafond: Pope Francis is an exceptional man with a very strong instinct to find the right path to the hearts of his visitors. I felt great hope and comfort that together we will find our way to wahkohtowin, Cree law for making relatives. And I recognize that it is an event that should have taken place 500 years ago.

Monstrous mountains of our own making are growing in number in the driest non-polar desert on Earth.

LASCAUX IS FAMOUS for its Paleolithic cave paintings, found in an underground complex in southwest France. The biggest area of Lascaux with the most abundant paintings is an echo chamber. Enveloped in sound, our human ancestors may have drummed and danced around a flickering fire whose shadows animated the natural scenes of people, animals, and their environment on the surrounding walls—all inviting transcendence. In ancient Greek religion, the lyrical music of Orpheus charmed the gods and compelled animals, even rocks and trees, to dance. Early Christian iconography developed a practice of liturgical art that both offered theological instruction and included details of the plant and animal world, both literal and allegorical, to foster spiritual reverence.

Closer to our time, great thinkers such as 19th-century German explorer-scientist Alexander von Humbolt looked beyond isolated organisms to the unity among plants, climate, and geography. In the 20th century, French Jesuit and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s perception that the universe is an evolutionary process moving toward greater complexity and consciousness furthered the understanding that humans are interdependent with the created world. Albert Einstein wrote that human beings experience ourselves “as something separate from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of consciousness” and that “we will have to learn to think in a new way” if humanity is to survive. This view is echoed in new developments in quantum physics that we may be evolving toward a more coherent wholeness among spirituality, science, and art.

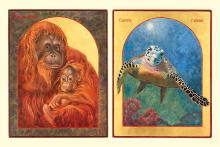

The icon paintings of Angela Manno, an internationally exhibited and collected artist, are yet another expression of this lineage in her series “Sacred Icons of Endangered Species.” I interviewed Manno by email and telephone in March.

Andrea M. Couture: As a contemporary artist, what attracted you to icon painting, one of the oldest forms of Christian art, going back to the third century?

Angela Manno: I’ve been fascinated by non-Western and ancient art forms throughout my life, from illuminated manuscripts as a child to batik while traveling through Indonesia in my early 20s; icon materials—gold leaf, pigments made from ground up semiprecious stones, earth colors; and the ethereal look of the finished product’s images of angels and saints.

In the 1980s, I developed my own personal idiom, combining the ancient art of batik with color xerography to symbolize the merging of intuition and reason. My aim was to convey a sense of the sacredness of the planet Earth. In the 1990s, no longer having access to my large studio and a photocopier, I searched for a medium that would allow me to work in a more modest space and, at the same time, I wanted to explore a truly liturgical art form. In a stroke of synchronicity, I had the opportunity to begin studying with a master iconographer from Russia in the Byzantine-Russian style, and became completely captivated by the symbolism, not only in the images, but in the process itself, and studied with him for over a decade.

WHEN JOHN BAGLEY JR. chose to attend evangelical Wheaton College in the mid-2000s, he said he was still trying to understand himself. As a Black queer man, Bagley said he spent a lot of his time after graduation just attempting to “put together the pieces of a lot of what was deconstructed or broken while ... in that environment.”

The year after Bagley graduated, he was contacted by a friend who was still a student at the school in Wheaton, Ill. The friend shared with him what would become known in Wheaton circles as “The Letter.” It was a message from students and alumni released following an April 2011 on-campus chapel series on “Sexuality and Wholeness.” The message from the college was clear: Heterosexual relationships were the only legitimate and faithful choice for Christians.

Wheaton alumnus Wesley Hill, author of Washed and Waiting: Reflections on Christian Faithfulness and Homosexuality, was among the series speakers that week, delivering a sermon based on his book, which chronicles his decision to be a “celibate homosexual Christian.”

“Many of us felt trapped and unable to respond honestly to these messages while we were students,” the alumni authors of “The Letter” wrote. To current LGBTQ students, they added, “your sexual identity is not a tragic sign of the sinful nature of the world. You are not tragic. Your desire for companionship, intimacy, and love is not shameful. It is to be affirmed and celebrated just as you are to be affirmed and celebrated.”

More than 700 alumni and students, including Bagley, signed the open letter. Bagley also became an informal member of an LGBTQ alumni group known as OneWheaton, which launched amid the controversy.

IN 1876, LAKOTA SIOUX rode on horseback from South Dakota to Montana Territory to help the Northern Cheyenne at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in one of the most important actions of the Great Sioux War.

The battle was inevitable. The rights promised through the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie, which gave the Sioux and Arapaho possession of the Dakota Territory, were being ignored. White miners had come to settle on part of the land that was sacred to the Lakota Sioux. The U.S. government ordered the Indigenous communities to return to their designated reservations. Instead of complying, they banded together as an act of resistance. Led by Lakota Sioux Chief Sitting Bull, the Indigenous resistance grew several thousand in number and ultimately defeated Lt. Colonel George Custer and the 7th Calvary—one of the worst U.S. army defeats during the Plains Wars.

Nearly 150 years later, members of the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne have joined forces once again to defend themselves against a new threat to their communal life: fossil fuels.

On the seventh anniversary of the martyrdom of the Mother Emanuel Nine, we still need to heed the text they were studying that evening.

Faith groups offer access to food and a model of sustainable solutions to food insecurity.

IN THE 1960s, Louise Morphis stored her money in a neighbor’s garage in the small town of Bynum, N.C. The rural Southern town’s white-run banks refused to serve the Black community, so the neighbor, vice principal of the local Black public school, housed a credit union in his garage through the 1990s.

“Some people go to the bank, some people have to go to the garage,” Morphis’ grandson, William J. “Bill” Bynum, told Sojourners. Those early memories of economic injustice stayed with Bynum, who was born in East Harlem and moved with his family when he was age 5 back to Bynum—“an old mill town actually named after my ancestors who had once worked there as slaves,” Bynum told the Delta Business Journal last fall.

In 1995, Bill Bynum helped found his own version of the “garage bank” his grandmother used. That seedling project, begun in the tithing room of a church in Jackson, Miss., became Hope Credit Union. Today, Hope has 23 branches and has generated more than $3.6 billion in financing in the Mississippi Delta region and across the Deep South.

Hope found its purpose in places where—as in Bynum’s hometown—entrenched generational poverty can be traced back to slavery. “If you look at a map of the country prior to the Civil War, and where slavery was concentrated, and a map today of where you have the worst job conditions, housing conditions, education outcomes, health outcomes, and where you have the fewest banks and the most payday lenders, they’re the same,” said Bynum, who serves as CEO of Hope Credit Union. “There’s a legacy of underinvestment and—no other way to describe it—institutional discrimination that limits opportunity.”

THERE ARE TWO churches in Newton County, Miss., that bear the name “Good Hope.” The first, Good Hope Baptist Church, was founded by white slaveholders in the 1850s. At least 20 African Americans were members of that church, forced to worship God alongside those who kept them enslaved. After the Civil War, Black members of the church banded together to form an independent community, the Freedman Settlement of Good Hope. One of their first goals as emancipated people was to establish a church of their own. Against immeasurable odds, they founded Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church in 1908. But that same year, terror threatened to rip the nascent community apart. Three congregants—William Fielder, Dee Dawkins, and Frank Johnson—were brutally tortured and lynched by a mob of at least 50 white men. The three were targeted for being associated with a Black sharecropper accused of killing his white employer. The mob went on to wreak havoc on Black neighborhoods. Traumatized by the violence and faced with restrictive Black codes that preserved white supremacy in the South, many members of the Freedman Settlement of Good Hope fled north.

But their families’ connection to that sacred ground didn’t waver. For more than 100 years, on the first Saturday in August their descendants have travelled from across the U.S. to the church for a revival. They sing, pray, and gather for a fish fry and soul food. They share news about marriages, births, and deaths. They listen to sermons and care for the cemetery where their ancestors are buried. And most importantly, they remember.

Last August, descendants gathered at Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Newton County for another reason: to unveil a historical marker honoring the memories of Fielder, Dawkins, and Johnson. The marker describes the terror that was unleashed on their community and the failure of local law enforcement to hold anyone accountable for the deaths and the destruction of Black property. Darrell Fielder, the great-great-grandson of William Fielder, told Sojourners he believes Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church was the appropriate space for “resurrecting” the legacies of these three victims. “It is the one space where Black people could practice a liberating faith and speak in frank terms about injustices,” Fielder said. “In placing these markers on church ground, we are honoring these martyrs and letting them know that God was always with them.”

TWO YEARS OF living through a pandemic has given us deeper insight into how extreme inequalities of income and wealth matter—and in some cases dictate who lives and who dies.

The pandemic economy supercharged existing inequalities, worsening the economic circumstances of the already precarious while further concentrating wealth and power in the hands of the already wealthy. In the first 21 months of the pandemic, roughly 700 U.S. billionaires saw their combined wealth increase by $2.2 trillion, even as millions lost their lives and livelihoods. A few hundred U.S. billionaires now have a combined wealth of $5.2 trillion, while the bottom half of all U.S. households—165 million people—have a combined $3.4 trillion.

It’s easy to see these inequality trends as invisible or remote forces without agency, or as failures of government policymakers to write the rules of the economy to ensure greater shared prosperity. However, there are private actors who function as “agents of inequality” whose daily work inflames existing divisions. These include what social scientists call the “wealth defense industry”—the veritable professional army of accountants, tax lawyers, wealth managers, and family office staffers that facilitates the hiding and sequestering of wealth.

These enablers serve the ultrawealthy—those with wealth upward of $30 million—and are paid millions to hide trillions. They labor to ensure that there is a two-tier tax system, with one set of rules for their ultrawealthy clients and another set of rules for everyone else. They also facilitate the creation of inherited wealth dynasties and monopoly power, directly exacerbating the existing racial wealth divide and entrenching concentrations of wealth and power.

The role of these enablers is in plain sight as nations around the world try to recover from the pandemic and find revenue to pay for it.

“WAIT—IS THAT Mr. C?” one of my students asked incredulously. “THAT’S MR. C?” he repeated, making a motion of his head exploding.

The rest of the class was reacting the same way, and I couldn’t help but laugh as I confirmed that, indeed, the person profiled in the documentary we were watching—a man serving a 35-year sentence for second-degree armed robbery—was indeed “Mr. C” (Charles Rodgers), the co-teacher of our class (via video) for the past two months.

Unbeknownst to them, my students had just concretely experienced the lesson with which we started the semester: Don’t judge a person by a single story.

The consequence of a ‘single story’

ACCORDING TO AUTHOR Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, there is great danger in a “single story.” The single story makes a single experience, characteristic, or action in a person’s life “become the only story,” and the only story, in turn, “creates stereotypes.” More important, Adichie says, when we make one part of a person’s incredibly varied life, experiences, and decisions the only story, “It robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar.”

I’ve been teaching Catholic social justice to high school students for nine years. My course always includes guest speakers, documentaries, and movies in which people can tell the fullness of their whole story. The full story allows students, in Adichie’s words, to recognize our “equal humanity” and to emphasize how we are similar. In Christian terms, the revelation of another person’s dignity allows for the possibility for conversion which, in my understanding, allows us to see the truth of another’s situation from a position of equality and solidarity, not judgment (whether positive or negative).

WHEN MAYA COMMUNITY educator Wilma Esquivel Pat opened a recent forum on the autonomy of Indigenous peoples, her remarks recalled her people’s struggle for self-determination in the Caste War of Yucatán—175 years ago.

European descendants had built lucrative sugar cane and henequen plantations on the peninsula that depended on Maya peasant farmers’ bonded labor. While the abolition movement was washing across the Americas, landholders on the Yucatán Peninsula began selling Maya prisoners of war and debtors into slavery in Cuba. In 1847, the Maya revolted and established an autonomous government in the eastern part of the peninsula that lasted through the turn of the century.

The era Esquivel Pat brought to mind remains recent, in generational time, for many Maya in attendance at the forum. Elders who held them as children may have themselves been cradled in the arms of elders who participated in that historic struggle. In them, their ancestors’ legacy reaches into the present. It’s a birthright they recall with pain and pride—the generations who resisted, as well as the white settlers and upper echelons of the colonial caste system who privatized land, exploited labor, and extracted returns at the expense of most of the region’s people.

Note: This article contains references to sexual trauma.

IT WASN'T SHEILA Wray Gregoire’s initial plan to make a career of writing about the intimate lives of evangelicals. But when she began her “mom blog,” To Love, Honor, and Vacuum, in 2008, she found her readers responded most when she wrote about sex.

Four years later, Gregoire wrote The Good Girl’s Guide to Great Sex and quickly found herself as a keynote speaker at conferences and churches throughout the United States and her home country, Canada. Recently, with her daughter Rebecca Gregoire Lindenbach and statistician Joanna Sawatsky, she wrote The Great Sex Rescue: The Lies You’ve Been Taught and How to Recover What God Intended to free women from toxic messages about sex and marriage often promoted in the church.

Gregoire told Sojourners she initially wasn’t aware of how pervasive these toxic teachings were. But after hearing from women that Love and Respect, a marriage advice book by popular Christian speaker Emerson Eggerichs (which boasts more than 2 million copies in sales), had been harmful, she read it for herself. She was horrified to find that the entire chapter on sex was addressed solely to women, instructing them to care for their husbands’ sexual needs. “Until then, we were working with blinders on as we created helpful resources to improve people’s marriages and sex lives,” Gregoire wrote in The Great Sex Rescue. “Once we read it, we realized that we needed to do far more.”

Sex as control

AS A CHRISTIAN couples therapist, I’ve been following Gregoire’s work and the backlash she has faced from some conservative evangelical men. Gregoire believes the teachings on women’s sexual obligations are due in part to who writes the books on sex and marriage popular in white evangelical churches: namely men, such as Eggerichs and Gary Thomas, author of Sacred Marriage. Other commonly read books are co-authored by couples, such as The Meaning of Marriage by Tim and Kathy Keller and The Act of Marriage by Tim and Beverly LaHaye.

As Lindenbach told Sojourners, “When you look at the best-selling books, when you look at who is running the organizations like Focus [on the Family] and Christianity Today, when you look at the people who are the most influential voices in evangelical Christianity, they are [mainly] men.” This influences how the church thinks about sex, she explains. “Most of the time, even the women who have influential voices are speaking on behalf of men.”

In writing The Great Sex Rescue, Gregoire, Lindenbach, and Sawatsky analyzed the popular marriage and sex books commonly read by evangelicals. They began with the top 10 Christian marriage books on Amazon, excluding those that did not significantly discuss sex. They also included other influential Christian books about sex, such as Every Man’s Battle by Stephen Arterburn and Fred Stoeker, and added a top-selling secular book, The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work by John M. Gottman and Nan Silver, for comparison.

While not all the books they reviewed were problematic, several contained harmful messages, such as viewing sex as a physical need only men have, rather than a mutual experience of intimacy, or blaming women for their husbands’ pornography use or affairs. Gregoire, Lindenbach, and Sawatsky also found exhortations that wives should maintain their appearance or weight as it was when they got married, arguing that failing to do so would be sinful. Many taught that women were prohibited from saying no to sex unless it was for a time of prayer and fasting approved by the husband. Of all the Christian books studied, none mentioned consent.

This article is adapted from Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World—And How to Repair It All (Brazos Press, a division of Baker's Publishing Group, Feb. 2022, used by permission).

ONE MONTH AFTER thousands of white nationalist men and women stormed the U.S. Capitol while attempting a coup d’état under Trump flags—resulting in the deaths of five people and assaults on 140 police officers—former President Trump’s second impeachment trial began. In the opening arguments, House impeachment managers rolled the tape, illuminating the truth of the horrors of Jan. 6, 2021.

The evidence presented for impeaching Trump was overwhelming, though many leading GOP members turned their eyes, busied themselves, and refused to reckon with reality. House Democrats voted unanimously for impeachment, and 10 Republicans joined them, making it the most bipartisan vote of its kind in U.S. history. While 57 senators found Trump guilty of “incitement of insurrection,” Trump was acquitted—even though the majority of senators found him guilty of leading a coup against the United States.

That vote revealed a fundamental malformation in our national governance. It is not new. It has been with us from the beginning—from the days when my ninth-great-grandmother, Fortune, was sentenced to indentured service, even though the Maryland race law that she was born under had been successfully challenged. The law changed after she was born, yet a judge—an arbiter of what is supposed to be true and just in our nation—bent the truth of the law to sentence her to generations of powerlessness, exploitation, and rape that she (and we) should not have had to endure.

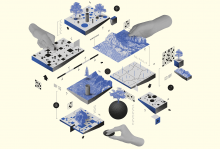

IN 1995, Bob Sabath, then-administrator of Sojourners’ new website, wrote about how the World Wide Web might expand and change faith communities. “This next decade may show that the greatest social impact of the computer is not as an office automation tool, but as a communication tool, as a community-building tool.” Sabath, a founder of Sojourners and now director of web and digital technology, wrote that the web “could become a useful tool for helping us find each other and the resources we need to do the work we feel called to do.”

This was a prescient view on a technology that was only at its early stages. Of course, no one could predict exactly how monumentally transformative that technology would be. Sabath wrote during “Web 1.0,” also known as the “read-only” era. Web 1.0 essentially provided digital brochures (or, for churches, bulletins); it gave users a way to access and read information but minimal opportunities for interaction.

Web 2.0, or the “read-and-write” era, gave people a way to interact with others and generate their own content. Myspace, YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter all represent read-and-write usages, but do so with online forums and web applications. It’s the type of internet most people are familiar with, even if not by name.

The currently developing era of the internet is known as Web 3.0. While definitions vary, decentralization is often a key component of technologies that fall under Web 3.0. Blockchains are one of those technologies, and they enable cryptocurrencies (such as Bitcoin and Ether) and nonfungible tokens (NFTs)—the digital art that exploded in popularity over the last year.

EVEN IN MY earliest memories, I was consumed by terrifying worries and did everything in my power to alleviate my deepest fears. When I was 8, I can remember being plagued by guilt following the death of my aunt to cancer, worrying that it was somehow my fault. Intrusive thoughts and images flooded my mind at night, and I called my parents into my room to confess, seeking reassurance that I was not a dangerous monster. As I grew older, my fears began to consume every single area of my life that was important to me. By college, I was afraid to sleep out of fear that I had left the stove on or the door unlocked. And by graduate school, I moved through my day wondering if I had called people derogatory names or written horrific things in birthday cards before blocking the memories out. I repeatedly checked the stove, took pictures of locks, and called friends to make sure I hadn’t somehow caused harm. At the time, I was unaware that these acts, known as “compulsions,” only made my condition worse.

In my early 20s, I learned that I was experiencing the symptoms of a diagnosable mental illness known as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD is often represented in television and movies as something laughable—think Tony Shalhoub’s Monk. In reality, OCD is far more serious: a debilitating disorder defined by unwanted obsessions that terrify the sufferer and compulsions repeated over and over to alleviate overwhelming fear, guilt, or anxiety. Some obsessions might relate to more commonly known themes of contamination or organization, while others might include culturally taboo themes involving violence or sex. But they are all equally painful to those caught in OCD’s grasp.

We all have thoughts—happy, sad, violent, intrusive, and strange. But those with OCD tend to place more value on these thoughts, concerned that they may be true. When time spent experiencing these obsessions and engaging in compulsions impedes functionality, that’s when it becomes a disorder. But even in my struggles, I feared documentation of an official diagnosis would negatively impact my pursuit of ordination. I had always heard that we should turn our worries to God, so I wondered what those approving my psychological evaluations for ministry would think if they viewed me as in need of mental health treatment that could not be solved through prayer.

THE SKIES ABOVE can give us a daily reminder that we are intrinsically part of God's creation. God not only created us with intent, but God also reached out to meet us in human history.

In this season of Advent, we remember the coming of Jesus Christ to earth. God became fully human and lived among us (John 1:14). As Eugene Peterson paraphrased it, “The Word became flesh and blood, and moved into the neighborhood” (John 1:14, MSG). Jesus’ body, like ours, was made of atoms that were once between the stars. In his incarnation, Jesus not only took up human form and human DNA but took up atoms that tied him to our planet, our sun, and the stars beyond. Yet he was still fully God!

Jesus Christ is the cosmic Creator. As John 1 declares, “All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being” (verse 3). I am still amazed whenever I remember that God, Creator of the galaxies, became one of us and walked the dusty roads of Palestine. How can humanity be insignificant if the Creator took on our form?

MAPS ARE NOT just drawings of a place; they are also windows into a perspective. In the era of European colonial expansion, maps were essential tools.

The 15th century imperial edicts known collectively as the Doctrine of Discovery theologically and politically justified the brutal seizure of land not inhabited by European Christians. This set into motion a new worldview that is the basis for all modern property ownership and established a relationship to the land based on colonization rather than habitation. As a result of this and other political arrangements, the Roman Catholic Church controls about 177 million acres of land around the world.

Molly Burhans is a Catholic, an activist, and an entrepreneur. She is also a cartographer and geographic information system (GIS) analyst who sees the church’s landholdings as an opportunity for a global spiritual and ecological transformation. If church maps in the past too often represented cultural oppression and land domination, the maps Burhans creates are powerful tools for ecological regeneration and social repair.

FOR YEARS, WOMEN called to leadership in the church in the Middle East have faced a stained-glass ceiling of limitations imposed by the surrounding patriarchal culture and theological presuppositions about the role of women in the church. But while some interpretations of Paul’s instructions to the early church (such as Timothy 2:12) are used as a rationale for limiting the role of women, long-standing cultural traditions regarding women’s roles in religion and society have played a more prominent, and more difficult, role.

“Although religion bears major responsibility for the inferior status of women, it cannot be solely blamed for the gender problem in the Middle East,” according to a report on “Women in the Middle East” published by the Institute for Policy Studies. “In reality, the role of culture has been even more prominent in perpetuating the oppression of women.”

Most denominations in the Middle East (other than Orthodox communions and the Catholic Church) do not prevent the ordina-tion of women for theological reasons. And many Protestant communions, such as the Lutherans and Presbyterians—which have been present in the Middle East since 19th century missionary encounters—ordain women in churches around the world. While Orthodox churches do not have women in positions of clerical leadership, Father George Massouh, then-head of the Center for Christian-Muslim Studies at the University of Balamand in Lebanon, explained in 2017 that the reason is not because of “theological hindrance.” Rather, Massouh said, the absence of ordained women in Eastern churches “was due to social customs”—the Orthodox church, he said, “has no such tradition, whether in Lebanon or anywhere else in the world.”

TRANSGENDER PEOPLE HAVE become a flash point in America’s culture wars, particularly in communities and institutions based on religious traditions that see the gender binary—the idea that human beings are always, and only, male or female—as a fixed theological principle rather than a mutable feature of human culture. The statement that God created human beings “male and female” (Genesis 1:27) is often cited as the basis for this belief, interpreted as meaning that binary gender is a divinely determined aspect of humanity—and transgender and nonbinary people, therefore, are not.

From this perspective, the gender binary is a cornerstone of the Divine-human relationship, a way in which God’s conception of humanity is reflected in our bodies, our intimate relationships, our families, customs, rituals, and communities. Transgender and nonbinary people—people like me who do not identify as the gender associated with the sex of our bodies—must either be deluded or heretical, misunderstanding who God means us to be, or consciously rejecting the Divine-human relationship and opposing the divine order of creation.

Whatever our motivations, our claims that human beings can really “be” transgender or nonbinary, and that such identities should be acknowledged and respected, are seen as posing an existential threat to the religious traditions that safeguard the sacredness of family, community, and humanity.