Lisa Sharon Harper, a former Sojourners columnist, is the founder and president of Freedom Road and author of Fortune and The Very Good Gospel. You can follow her work at lisasharonharper.com.

Posts By This Author

The Capitol Attack Held Up a Mirror to the Nation

A year after Jan. 6, we must reckon with what the country has become since its founding.

This article is adapted from Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World—And How to Repair It All (Brazos Press, a division of Baker's Publishing Group, Feb. 2022, used by permission).

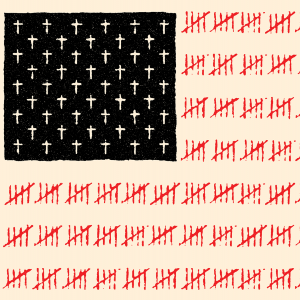

ONE MONTH AFTER thousands of white nationalist men and women stormed the U.S. Capitol while attempting a coup d’état under Trump flags—resulting in the deaths of five people and assaults on 140 police officers—former President Trump’s second impeachment trial began. In the opening arguments, House impeachment managers rolled the tape, illuminating the truth of the horrors of Jan. 6, 2021.

The evidence presented for impeaching Trump was overwhelming, though many leading GOP members turned their eyes, busied themselves, and refused to reckon with reality. House Democrats voted unanimously for impeachment, and 10 Republicans joined them, making it the most bipartisan vote of its kind in U.S. history. While 57 senators found Trump guilty of “incitement of insurrection,” Trump was acquitted—even though the majority of senators found him guilty of leading a coup against the United States.

That vote revealed a fundamental malformation in our national governance. It is not new. It has been with us from the beginning—from the days when my ninth-great-grandmother, Fortune, was sentenced to indentured service, even though the Maryland race law that she was born under had been successfully challenged. The law changed after she was born, yet a judge—an arbiter of what is supposed to be true and just in our nation—bent the truth of the law to sentence her to generations of powerlessness, exploitation, and rape that she (and we) should not have had to endure.

Will White People Choose Beloved Community?

People of European descent have a simple choice.

I SCROLLED THROUGH the “Moving Mountains” columns I’ve plunked out on laptop keyboards over the past decade. Each title marks a particular threshold in my own journey and understanding. As titles roll from top to bottom, one thing becomes clear as crystal: I have shared my life and my heart with you. This column has largely served as sacred space to reflect, from the perspective of a Black woman follower of Jesus, on the mountains we face, the strategies and tactics it will take to move them, and the faith it takes to move our feet at all. I am grateful to you, the Sojourners community, for all your emails and tweets. Thank you for reading my words.

A recent New York Times article, “Can This Amusement Park Be Saved?” did a deep dive into the fate of the Clementon Park and Splash World, located just across the Delaware River from my home in Philadelphia. Seeded by Civil War veteran and New Jersey Assemblyman Theodore B. Gibbs in 1907, this New Jersey amusement park found its heyday in the late ’40s and early ’50s, but fell into disrepair, refinance, and repossession, finally being auctioned off this year. Indiana-based developer Gene Staples won the auction with a bid of $2.37 million and aims to restore the amusement park to its former glory.

Reporter Kate Morgan writes, “the true draw, [Staples] believes, is the nostalgia itself; the promise that you can go home again, and when you get there, you’ll recognize the place.”

Dreaming My Home Into Being

Let's think beyond a survival mentality.

HABITS ARE FORMED in response to contextual cues. The stronger the cue, the harder it is for our minds to access alternative responses.

We just spent four years resisting. We became experts at pushing back, filling public squares, locking arms. Some of us also built habits of self-care. We would receive the cue for a big justice push and, without thinking, plan a day of hibernation on the other side. These habits were (and are) beautiful and necessary. But now we live in a new context. The old cues that triggered those habits will come less and less frequently. It is entirely possible that a year from now we could find ourselves coasting on autopilot rather than establishing new habits of dreaming and building what we dream.

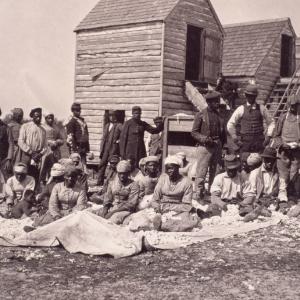

By the end of the Civil War, 4 million enslaved people of African descent were sustaining themselves with survival habits cultivated and passed down over the course of 250 years. They found themselves in a brand-new context on April 10, 1865. Survival was no longer the highest goal. Now they were free to dream.

Three Practices for Healing in 2021

Let's dance and shake 2020 out of our systems.

FOUR YEARS of verbal abuse. Four years of draconian policies that eviscerated the dignity of people who were not white, Christian, male, or citizens; of police-involved fatal shootings of Black men, women, and children with impunity; increasing climate disasters; government corruption; Russian bots and “fake news”; “very fine people on both sides”; families ripped apart; the white church’s loyalty to whiteness, not Brown Jesus. Four years of betrayal. Four years.

And one year of COVID-19, of disaster coupled with a disastrous response, of hibernation. One year of death.

We are a traumatized nation. As the U.S. enters the next era with a new administration, it is tempting to do as our foremothers and forefathers were taught: When they returned home from a war or survived domestic abuse, they were counseled to put it behind them. They didn’t talk about it, and the wounds grew scars, and the scars took over the bodies of our family systems.

Five Things We Learned From 2020

What brought us to this brink of a broken democracy?

1. Character matters

In 2016, we heard the recording of Donald Trump bragging that he could grab women by the genitalia and kiss them without consent. This reveal of sexual abuse was a blinking red warning sign: “No character!” But most white American Christians voted for him anyway. Now hundreds of thousands of Americans are no longer with us. Children are dead, separated from their parents, neglected and abused in our detention centers. Police continue to kill unarmed Black people with impunity. Evidence shows that wherever there is violence against women, there will also be violence against ethnic minorities and the land. Character matters.

2. Our votes matter

If you ever doubt that, remember 2020: body bags, 175 cities on fire, food lines, closed businesses, fears for the future, the president having tear gas shot into a crowd so he could walk across the street and hold a Bible in front of a church he doesn’t attend. Let us learn that a non-vote is a vote for the winner. In a democracy, votes have the power to bless or curse millions. It is our civic duty to approach elections as informed citizens. It is our Christian duty to leverage elections to protect the least of these.

Now Is the Time to Dream the Next America

Americans must vow to never relive the ongoing horror of 2020.

THE DARKEST HOUR, as they say, comes one sliver of a moment before dawn. We have been experiencing our nation’s darkest “day” since well before the moment the Confederacy fired its first shot at Fort Sumter in Charleston, S.C. That cannonball tore time in two, each successive battle of the Civil War ripping the sky farther and farther apart. After the war we saw stars, possibilities—the 13th and 14th and 15th Amendments to come.

Between May 28 and June 1 of this year, flames rose from numerous U.S. cities. One fire leveled a cinder-block structure that housed bathrooms and a maintenance office near the White House grounds. In the darkness we were forced to confront our hearts when tears filled our eyes as we watched a Starbucks burn, in the shadow of our numbed response when we first learned of George Floyd’s death—another Black person dead. Yes, property damage is mournful. The destruction is a crime because of the impact the losses have on people. But no, this kind of property damage is not “violent,” not in the manner of violence against people, which defaces the image of God, or against anything that holds the breath of God. Buildings are made by people, not by God. Nor do brick and mortar hold the breath of God. They do not feel. They do not have a family. Things can be replaced. Life cannot.

Returning to My Body After Trauma

If we listen to our bodies, they will tell us where God wants to heal our souls.

AS WE SAT in the third row of the movie theater, dread washed over me. Would my neck survive this two-hour Spike Lee Joint? I leaned against my non-plush movie seat and looked up at BlacKkKlansman, laughing, gasping, and, as always, appreciating Lee’s cinematography.

Then, in the final frames of the film, Lee broke the fourth wall to speak directly to his audience. In an instant, we were transported from 1970s Colorado Springs to Aug. 12, 2017, Charlottesville, Va.

My body seized up. Even as my fingers peck out these words, my body is charged with energy. I was there. Hundreds of faith leaders offered public witness in Charlottesville that day. We declared to the world, “There is another way!” Among many other people, 80 priests, pastors, imams, rabbis, and faith leaders walked arm-in-arm to what was then called Lee (now Emancipation) Park, where white supremacists were protesting the removal of a statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. We found men armed with AR-15s, guarding “their” turf.

When Voters are Too Traumatized to Take Chances

Perhaps in normal times black voters would take a risk with their ballot. But for Southern black families, the results of this election will mean life or death.

IN EARLY MARCH, as part of a weekend of events in Selma, Ala., to commemorate the 55th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” MSNBC’s Joy Reid and DNR Studios’ Mark Thompson moderated conversations with presidential candidates. When Elizabeth Warren took the stage, the racially mixed audience roared, many attendees holding signs in the air that read “Warren for President.”

Many black women activists, advocates, and leaders endorsed Warren early in the race for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. Black Womxn For, a coalition of more than 100 black women influencers, endorsed her in late 2019. I endorsed her in February 2020, as did Black Lives Matter co-founders Alicia Garza and Patrisse Cullors. At the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, the premiere annual gathering of justice-minded black clergy, her name buzzed in hallways and around dinner tables. She had listened deeply to the African American community and many other marginalized communities, and the result was a deeply intersectional platform.

So, when Super Tuesday came, I was hopeful that black women across the South would go to the polls with enthusiasm for Warren. But overall, they didn’t. Joe Biden won the black vote throughout the South. What happened?

What Does the Lord Require of White Women?

Why white women have, historically, been disappointing allies to women of color.

OVER THE LAST six months, I’ve spoken with multiple white women across the country about something I am beginning to understand: why white women have, historically, made disappointing allies to women of color.

These words feel dangerous to utter. I risk alienating women I love and admire. But they must be spoken in a year when the actions and votes of white women will impact the lives of women of color and their families more so than any time since women gained suffrage. We must lean into this hard conversation—and, in the doing, place our hope in the power of the resurrection, asking brown Jesus to illuminate what an alliance with women of color will require of white women in 2020.

An early race law in the colony of Maryland, where Harriett Tubman was enslaved, mandated that any white woman who married an enslaved black man would herself become a slave until her husband died. By the antebellum era, it was established that white women could not be enslaved but that ownership of their property (including their bodies) transferred to their husbands upon marriage. They could not sue. They could not make a legal contract. And they could not vote.

White patriarchy’s rule, and the ever-present threat of being shunned, gave white women incentive, when push came to shove, to choose their whiteness over their womanhood.

We—the Church—Are Being Re-formed

“My most potent times of worship have happened while locked arm in arm with Jesus followers.”

EVERYWHERE I GO I’m having the same conversation: Young and old alike seem to be streaming out of the church. On Oct. 17, the Pew Research Center released an update on America’s changing religious landscape. According to Pew, “The share of U.S. adults who are white born-again or evangelical Protestants now stands at 16 percent, down from 19 percent a decade ago.” Christians are attending church at the same rate as a decade ago, but fewer people are identifying as Christian.

Church-attendance rates among affiliated Christians haven’t risen as the dispassionate have left. It seems passion for church is dimming even among the affiliated. In conversations across America, I hear the same mantra: “Church hurts too much.”

I get it.

I haven’t had a home church since December 2015. On that last Sunday, amid the river of hashtagged lives that has flowed across social media since Trayvon Martin’s murderer was set free in 2013, a pastor rose to the stage. White, male, and hip, he stood in the heart of empire—Washington, D.C.—and flipped through sacred texts written by brown, colonized, and serially enslaved people, landing on the book of Acts. He read a passage from the book that chronicles how the Holy Spirit moved through the earliest church to destroy hierarchies of human belonging imposed by empire. He read the passage and never came back to it. Later, hundreds of people swayed to three chords, inspired by the Bible’s teaching on how to overcome conflict at a workplace.

There Is Healing In the Water

A pilgrimage through stories of oppression leads to Lake Sakakawea.

OVER TWO MONTHS, I’ve been on three pilgrimages through stories of oppression in the U.S., water figuring prominently in each. Leaving the Whitney Plantation and rolling through nearby Louisiana bayous, I imagined African-descended men and women masking themselves in troubled waters from slave catchers. Rolling through the desert between San Antonio and McAllen, Texas, I imagined people of Spanish, African, Aztec, Mayan, and Incan origin scouring barren land in search of water, and flourishing.

Then I spent a week with my friend Ruth Anna Buffalo and her family and friends. Ruth is an enrolled member of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation and the first Native American Democratic woman elected to the North Dakota legislature. Early in our time together, Ruth shared the story of her tribe’s movement north, from present-day Standing Rock. The Mandan settled in the bottomlands of Elbowoods.

From 1949 to 1956, the U.S. Department of the Interior built the Garrison Dam and intentionally flooded the treaty-bound lands of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, along with more than 20 other tribes, to save white communities experiencing natural flooding downriver. They named the human-made reservoir Lake Sakakawea. Elbowoods—the land where Ruth’s family flourished—is now under the water. And whites have claimed the “lakefront” property.

The Modern-Day System of Leasing Immigrants

Moving immigrant exploitation back inside of prisons.

MY LATEST PILGRIMAGE took me and three fellow travelers across two states. As we wound along serpentine country roads in an SUV, the open fields and swamps that lined our path seemed haunted. “Come, listen,” tall, tall trees whispered. “We have a story to tell.”

From the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana to Jim Crow convict leasing in Sugar Land, Texas, to the Alamo—where a battle was fought to protect Texan slavery and Latinos were racialized—to our current-day militarized border lands, Southern soil has borne witness to a baseline of U.S. economic strategy: exploitation of immigrant labor.

‘This is the Cost of Our History’

I dug into my family’s past, and now it haunts me.

TWO OF MY favorite television shows are Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Who Do You Think You Are? Both shows walk celebrities through the process of discovering their ancestors’ stories. I could watch them for hours (and sometimes have).

I love them, but I am also frustrated by them. Because the history of American families is American history, those families’ stories inevitably intersect with major U.S. events: the removal and genocide of Native Americans, slavery, the Salem witch trials, the suffrage movement, prohibition, the great migration, Jim Crow, the list goes on. Usually, these shows give about one minute for celebrities to process their ancestors’ roles in these monumental moments, then move on. Celebrities whose ancestors participated in American westward expansion are often celebrated as “pioneers” whose courage and grit helped forge America. Rarely are they guided to understand that their ancestors participated in the removal and genocide of Indigenous nations who stewarded the same land for tens of thousands of years before Europeans “pioneered” it.

Recently, I dug into the story of my third great-grandmother, Lea Ballard, who is the last adult enslaved person in our family. Her daughter, Martha, died while giving birth to my great-grandmother, Elizabeth.

To Be Black and Christian in Brazil

The lessons of slain Brazilian civil rights leader Marielle Franco cannot be forgotten.

MORE THAN 50 black women and a handful of black men huddled in a narrow room of an unmarked church on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. The women were adorned with natural hair and were happy to be together, but I noticed a seriousness about them. Many had traveled two hours or more via public transportation. This was not just a meeting: It was an event.

Our gathering formed in the shadow of Brazil’s recent election. Jair Bolsonaro won the Brazilian presidency, promising to target black women activists, LGBTQ people, and others and to bring in militarized security forces to squash violence in shantytown communities known as favelas. Seventy percent of evangelical Christians voted for Bolsonaro, giving him his win.

At our meeting, worship leaders led the women in singing songs about the God who promises a day when oppression will be lifted. One of the songs honored the brown, colonized girl named Maria, whose Magnificat promised these women’s liberation.

A year has passed since the assassination of 38-year-old black Rio de Janeiro councilwoman Marielle Franco. Franco, who challenged police brutality and extrajudicial killings, was shot while riding in the back seat of a car. Two hours before she was slain, she called for black women to engage in politics to bring about a just Brazil. The bullets that killed her were purchased in 2006 by federal police in the nation’s capital city of Brasilia.

Brazil’s Carnival has presented the country as a happy, diverse nation where black women can dance without shame or consequence. I didn’t know Brazil was the last nation in the world to abolish slavery and that 4.8 million Africans were shipped there over a span of nearly 400 years. I also didn’t know that after abolition in Brazil, the Portuguese elite begged Europeans to “whiten” their mostly African nation and “civilize” it. They promised 4 million Europeans seeds and free transportation to Brazil, while formerly enslaved Africans received nothing.

When Evangelicals Had Integrity

This past year exposed assaults on the rules of law, public ethics, and moral decency.

AS I FLIPPED the pages of Timothy L. Smith’s classic, Revivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil War, a question came to mind: Why did 19th-century evangelicals bundle social concerns, such as slavery and suffrage, with issues that seemed more prudish, such as temperance?

According to historian Ken Burns, by the year 1830 American men consumed seven gallons of alcohol per year, three times more than they consume today. In an era when white women had few legal rights, the scourge of alcohol-related domestic violence gave rise to an evangelical-led grassroots movement that called for temperance and prohibition. It wasn’t a “prudish” venture at all, but rather a progressive reform movement aimed at protecting women from violence and abuse.

The same evangelical women and male allies who pushed for temperance also stepped forward on the front lines of the fights for abolition and women’s suffrage. They had witnessed the fruit of William Wilberforce and the Clapham Group’s fight to end the transatlantic slave trade through England’s 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. That monumental victory led the U.S. Congress to pass a similar act the same year. This should have led to abolition, but instead led to the explosion of the U.S. chattel slave economy, a result of the rise of the cotton gin, the establishment of the second Middle Passage from the upper South to the Deep South, and the entrenchment of the barbaric practice of “breeding” free labor. Though the government had outlawed the importation of slaves from Africa, it did not abolish its slave-based economy, but rather expanded it.

An Open Letter to White Evangelicals

At best, many of you have been silent.

IN 1983, I walked down an aisle at a Sunday evening church camp meeting in Cape May, N.J., and bent my brown knees at the altar. I had spent a year learning the basics of our faith. I had done walk-a-thons and sing-a-thons as part of a small youth group in a local Wesleyan church. I had sat through countless altar calls at Christian concerts. But now I was ready to surrender to Jesus. It was glorious when it happened: Surrendering to a relationship with him was an act of freeing myself from fear. I trusted Jesus with my life.

Freedom from fear means freedom to love—to love like the Good Samaritan loved—without limits and concern for self. This kind of love is witness. It requires belief that Jesus’ way is, indeed, the way, that Jesus’ words are the truth and will lead to good life. To love someone of another ethnicity, for example, as extravagantly as the Samaritan loved, one must believe that Jesus has got our back when we follow his lead.

Conservative Court-Packing Isn't About Abortion—It's About Culture

If the Right really cares about abortion, they should reduce poverty.

From ‘war on poverty’ to ‘war on drugs’

SCOTUS: Evangelicals Are Pledging to Pause the Culture Wars

We don’t often think of our current-day allegiances existing within decades, even centuries, of struggle. Sometimes they do. With the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court, President Donald Trump has pushed our nation to an existential point of decision about who we are and who we will be for at least the next two to three generations.

The Theory of the Shrunken Heart

“For centuries, white people have shrunken their own hearts.”

THERE IS A short film embedded in the wall just to the left of the welcome desk in the lobby of the Equal Justice Initiative’s new Legacy Museum, which opened to the public on April 26. The first time I visited the museum, I stood in a crowd watching the video and tried to comprehend the story. An African-American girl clung to her father’s neck as he carried her, walking slowly toward white men standing in a field. The setting? The Antebellum South.

That film left me weeping—near wailing—right there in the lobby.

A few weeks later, I returned with participants on a weeklong pilgrimage through the history of the control of African bodies on U.S. soil. The journey—offered for continuing education and graduate credit through Greenville University—began in Montgomery, Ala., at the Legacy Museum. Each of the participants watched the video. One woman was so overwhelmed with grief that she had to leave the museum.

The Legacy Museum and the accompanying National Memorial for Peace and Justice shine light on details that have been hidden from us. They help us understand the humanity of the oppressed and the cruelty of slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, and present-day police brutality.

Trump vs. Jesus

Has the Trump presidency revealed a truth about evangelical America that we have not wanted to see?

I HAIL FROM a theological tradition that places the highest value on epistemology, the study of how we think about God, yet tends to invest little energy on ethics, the study of how we are called to interact in the world.

Likewise, many in my theological tradition place ultimate value on one’s capacity for faith in particular sets of beliefs—and tend to demonstrate hostility toward historical, anthropological, philosophical, and scientific methods to shape those beliefs, unless those methods happen to support the tradition’s faith-born premises. Think: climate-change denial. This article of faith is partially rooted in profound belief in a particular reading of Genesis 1:26 and human dominion. It is not rooted in science.

Perhaps this reveals one reason why so much of the white evangelical community saw no red flags when Donald Trump refused to show his tax returns. They believed in him. They did not need to see evidence.

Perhaps this is the reason it does not faze many white evangelicals that Trump trafficked in fake news, conspiracy theory, and innuendo to win the presidency and continues the practices in the aftermath. Trump’s relationship to fact may mirror their own. It almost seems as if life in this world and the hard facts that govern life have nothing to do with anything. I’m thinking of the fold-over tracts or Facebook posts that fly through evangelical circles during every presidential election cycle. They claim the Democratic candidate is the Antichrist and warn of the horrors if she or he is elected. It doesn’t matter if the Democrat or the Republican promises to protect the poor. All that matters is which one assures the voter’s stature in the afterlife. And who wants to go to hell because they voted for the Antichrist? Not me.