LASCAUX IS FAMOUS for its Paleolithic cave paintings, found in an underground complex in southwest France. The biggest area of Lascaux with the most abundant paintings is an echo chamber. Enveloped in sound, our human ancestors may have drummed and danced around a flickering fire whose shadows animated the natural scenes of people, animals, and their environment on the surrounding walls—all inviting transcendence. In ancient Greek religion, the lyrical music of Orpheus charmed the gods and compelled animals, even rocks and trees, to dance. Early Christian iconography developed a practice of liturgical art that both offered theological instruction and included details of the plant and animal world, both literal and allegorical, to foster spiritual reverence.

Closer to our time, great thinkers such as 19th-century German explorer-scientist Alexander von Humbolt looked beyond isolated organisms to the unity among plants, climate, and geography. In the 20th century, French Jesuit and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s perception that the universe is an evolutionary process moving toward greater complexity and consciousness furthered the understanding that humans are interdependent with the created world. Albert Einstein wrote that human beings experience ourselves “as something separate from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of consciousness” and that “we will have to learn to think in a new way” if humanity is to survive. This view is echoed in new developments in quantum physics that we may be evolving toward a more coherent wholeness among spirituality, science, and art.

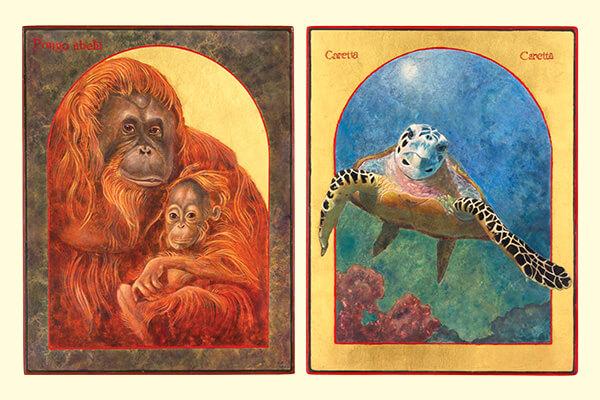

The icon paintings of Angela Manno, an internationally exhibited and collected artist, are yet another expression of this lineage in her series “Sacred Icons of Endangered Species.” I interviewed Manno by email and telephone in March.

Andrea M. Couture: As a contemporary artist, what attracted you to icon painting, one of the oldest forms of Christian art, going back to the third century?

Angela Manno: I’ve been fascinated by non-Western and ancient art forms throughout my life, from illuminated manuscripts as a child to batik while traveling through Indonesia in my early 20s; icon materials—gold leaf, pigments made from ground up semiprecious stones, earth colors; and the ethereal look of the finished product’s images of angels and saints.

In the 1980s, I developed my own personal idiom, combining the ancient art of batik with color xerography to symbolize the merging of intuition and reason. My aim was to convey a sense of the sacredness of the planet Earth. In the 1990s, no longer having access to my large studio and a photocopier, I searched for a medium that would allow me to work in a more modest space and, at the same time, I wanted to explore a truly liturgical art form. In a stroke of synchronicity, I had the opportunity to begin studying with a master iconographer from Russia in the Byzantine-Russian style, and became completely captivated by the symbolism, not only in the images, but in the process itself, and studied with him for over a decade.

Read the Full Article