Andrea M. Couture, a writer in New York City, has had two careers—international and domestic social issues and the arts—and delights in combining them.

Posts By This Author

Creating a Sense of Reverence for Every Species

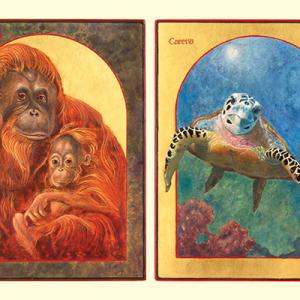

Angela Manno's "Sacred Icons of Endangered Species" shed light on the holy work of loving the Earth.

LASCAUX IS FAMOUS for its Paleolithic cave paintings, found in an underground complex in southwest France. The biggest area of Lascaux with the most abundant paintings is an echo chamber. Enveloped in sound, our human ancestors may have drummed and danced around a flickering fire whose shadows animated the natural scenes of people, animals, and their environment on the surrounding walls—all inviting transcendence. In ancient Greek religion, the lyrical music of Orpheus charmed the gods and compelled animals, even rocks and trees, to dance. Early Christian iconography developed a practice of liturgical art that both offered theological instruction and included details of the plant and animal world, both literal and allegorical, to foster spiritual reverence.

Closer to our time, great thinkers such as 19th-century German explorer-scientist Alexander von Humbolt looked beyond isolated organisms to the unity among plants, climate, and geography. In the 20th century, French Jesuit and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s perception that the universe is an evolutionary process moving toward greater complexity and consciousness furthered the understanding that humans are interdependent with the created world. Albert Einstein wrote that human beings experience ourselves “as something separate from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of consciousness” and that “we will have to learn to think in a new way” if humanity is to survive. This view is echoed in new developments in quantum physics that we may be evolving toward a more coherent wholeness among spirituality, science, and art.

The icon paintings of Angela Manno, an internationally exhibited and collected artist, are yet another expression of this lineage in her series “Sacred Icons of Endangered Species.” I interviewed Manno by email and telephone in March.

Andrea M. Couture: As a contemporary artist, what attracted you to icon painting, one of the oldest forms of Christian art, going back to the third century?

Angela Manno: I’ve been fascinated by non-Western and ancient art forms throughout my life, from illuminated manuscripts as a child to batik while traveling through Indonesia in my early 20s; icon materials—gold leaf, pigments made from ground up semiprecious stones, earth colors; and the ethereal look of the finished product’s images of angels and saints.

In the 1980s, I developed my own personal idiom, combining the ancient art of batik with color xerography to symbolize the merging of intuition and reason. My aim was to convey a sense of the sacredness of the planet Earth. In the 1990s, no longer having access to my large studio and a photocopier, I searched for a medium that would allow me to work in a more modest space and, at the same time, I wanted to explore a truly liturgical art form. In a stroke of synchronicity, I had the opportunity to begin studying with a master iconographer from Russia in the Byzantine-Russian style, and became completely captivated by the symbolism, not only in the images, but in the process itself, and studied with him for over a decade.

A Public Advocate Takes the Stage

Through Theater of War, Brooklyn's Jumaane Williams helps audiences process tragedy.

AS NEW YORK CITY'S elected public advocate since 2019, Brooklyn native Jumaane Williams is the ombudsman for more than 8 million people in all five boroughs, charged with overseeing city agencies and investigating citizen complaints. And, starting in 2016, when he was a member of the New York City Council, he has performed in more than 40 staged readings of plays, most of them classical tragedies, with Theater of War Productions.

Starting in 2009 with a performance of scenes from “Ajax” and “Philoctetes” by Sophocles that highlighted the issue of military PTSD, Theater of War Productions has presented dramatic readings of classical Greek tragedies and other plays followed by guided discussions linking their themes to contemporary social issues. It now has a repertory of more than 20 works addressing a wide range of complex social issues—from racism to refugees, gun violence to sexual assault, frontline medical worker mental health to criminal justice, and more. Essential to the experience are post-performance discussions in which audiences engage with the play’s themes, creating cathartic release and deepening understanding. During the pandemic, Theater of War has gone online, reaching a vast international audience.

Nigeria, Iraq, and Greece Want Their Artifacts Back

What's taken with an artifact? Transgenerational identity, memory, knowledge, ritual, inspiration, self-esteem, and agency.

THIS ISN'T A lion: It’s a miracle. You can almost hear the imperious growls that would have thundered in the imaginations of pedestrians approaching ancient Babylon’s Ishtar Gate. They would have walked along the Processional Way to enter the inner city, flanked by cerulean blue tile walls with 120 nearly life-sized lion bas-reliefs—a spectacle!

Not so in 1899, when German archaeologists arrived on the banks of the Euphrates—80 miles from Baghdad—and dug until 1917. Babylon’s splendor had been reduced to mounds of thousands of glazed brick fragments, which would fill nearly 800 crates sent to Berlin. There, each piece was laboriously cleaned, stabilized with modern material, sorted and assembled into whole bricks, and ultimately restored into panels of proudly parading beasts in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum. Iraq has been trying to get them back since the 1990s.

For nearly two centuries the Greeks and the British have been arm wrestling over the Parthenon Marbles—including a lengthy frieze of a mythical Greek feast, a muscled river god, and voluptuous female figures—taken from the Acropolis in Athens and now displayed in London’s British Museum. Lord Elgin was Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, which encompassed Greece. Greece claims that Lord Elgin stole them, that the sale was illegitimate since Greece was occupied, and that they should be returned.

Artists Are Transforming Objects 'Created for Evil' Into Works of Beauty and Power

Four artists who chose to turn trauma into sights to behold.

HANNAH ARENDT SAID we can ask of life, even in the darkest of times, a “redemptive element,” and art can be that—an affirmation of right, light, truth, some beleaguered beauty. But note well: Art is no escape from the problems of the world but, rather, a repurposing, a resistance. And, of course, this phenomenon of violence into art can go both ways. Michelangelo’s bronzes, including his colossal papal statue of Pope Julius II, were melted down into cannons and other weapons during the French Revolution. It’s our choice.

Here are four artists who chose to turn trauma—civil war, natural disasters, apartheid, and female genital mutilation—into sights to behold.

Ralph Ziman, South Africa

Designed and put into service in apartheid South Africa in the 1980s, the so-called Casspir, a mine-resistant and ambush-protected vehicle, has been subverted. Says South African artist Ralph Ziman: “The Africanization of the Casspir seemed to take away the terror it once evoked ... people felt comfortable to approach it, touch it, and share their stories and memories.” He elaborates on his intention: “To make this weapon of war, this ultimate symbol of oppressing ... to reclaim it, to own it, make it African, make it beautiful, make it shine.”

Born in South Africa in 1963, Ziman grew up in a strict system of institutionalized racial segregation and political and economic discrimination—“apartheid,” which translates in Afrikaans to “apartness.”

“I have vivid memories,” he says of his first sighting of a Casspir. It was April 1993. Charismatic leader Chris Hani had been gunned down outside his house in a Johannesburg suburb by a white nationalist. The artist drove to the funeral and saw columns of Casspirs descending the dusty streets; heavily armed police fired tear gas, shotguns, and automatic weapons. More of the same occurred the next day in Soweto, where police and army units parked their Casspirs along the highway and exchanged gunfire with members of the African National Congress. “Tear gas and smoke burned our eyes and into our memories, along with the sight of armed men on the Casspirs ... for me, covering this beast with beads is catharsis,” says Ziman.