Arts & Culture

If you ask TV writer and producer Vince Gilligan what his latest show, Pluribus, is about, he’ll turn the question right back around on you.

“I really like the idea of making a show and letting viewers tell us what it’s about,” Gilligan told Sojourners. “I don’t know that there’s any one answer to that question other than what the individual thinks.”

“This world is intricately stitched together, boys. Every thread we pull, we know not how it affects the design of things,” muses William H. Macy’s Arn Peeples, an aging tree logger in Train Dreams. Throughout their ongoing work on the construction of the Spokane International Railway, laborers like Arn occasionally ruminate on their place in a broader human tale of hubris and glory, though they don’t have all the answers.

Indeed, the world is intricately stitched together. And the same could be said about the film itself, though, moment by moment, it gives the feeling of a wandering walk in the woods. Much like Arn, director Clint Bentley and screenwriter Greg Kwedar seem aware of their lack of answers—but find asking the questions worthwhile anyway.

In Rental Family, Brendan Fraser’s character Phillip does a lot of pretending. While looking for gigs as an American actor living in Tokyo, he lands a strange role: “token white guy.” And it gets weirder, the more Phillip learns about it: His new employer, a company called “Rental Family,” doesn’t cast for the stage or the screen. They hire actors—“surrogates”—to play roles in people’s lives, to “help people connect to what’s missing.”

Phillip becomes whatever the company’s clients need him to be: a mourner at a staged funeral, a groom for an anxious bride, the dad who’s finally part of the picture. Sometimes he pretends to be these people for 30 minutes, sometimes he has to pretend for weeks on end. Soon, Phillip comes to love the job he was initially so skeptical of.

One of the stranger moviegoing experiences of my life was walking out from The Last Jedi and feeling sure I’d experienced a masterpiece. I’m not the most devoted Star Wars fan, but I thought I’d seen something special. I still do. So, you can imagine my surprise when the rest of the world was, shall we say, a little divided on The Last Jedi.

I’m not here to relitigate that whole exhausting conversation now. But while watching that movie, I felt a connection to the filmmaker, Rian Johnson. Something in the way he navigated the power of belief, the handing down of received wisdom, and the challenges of carving new paths in old traditions spoke to me. I was not surprised to later learn that Johnson had been raised in the church, and I was delighted when he decided to take that as both the theme and setting of the third Knives Out film, his wildly popular murder mystery franchise starring Daniel Craig’s Foghorn Leghorn-throated detective Benoit Blanc.

FOR MONTHS, I’VE tried to understand the outrage over the selection of rapper Bad Bunny as headliner of the Super Bowl LX halftime show. What’s not to like about the Puerto Rican reggaeton star? He’s won three Grammys, boosted Puerto Rico’s economy by at least $400 million with his concert residency, and through his “Good Bunny” foundation annually delivers thousands of Christmas gifts to Puerto Rican children—even though it would be far more on-brand for him to deliver Easter baskets.

Still, after the announcement, conservatives across the country revolted (sent out angry tweets on X, which somehow still exists). They wanted a Christian, American halftime show, not a secular, Puerto Rican halftime show! Soon they learned that every Puerto Rican is a U.S. citizen and that by nearly every metric of religiosity, Puerto Rico ranks as the most Christian jurisdiction of the United States. These facts didn’t assuage their anger.

Sufjan Stevens’ Songs for Christmas boxset includes a memoir essay about how the smell of a burning spatula sent him tumbling into old Christmas memories and, eventually, something like a spiritual revelation—“a tragic-comic-sentimental shock that was simultaneously mundane and supernatural.”

In the vision Stevens describes, the smell of melting plastic becomes a portal to the whole universe, past and present, and “at the very center of the universe I saw the Christ Child … This was the mysterious Incarnation of God. It feels about right that Stevens would treat Christmas like both a theological mystery and a craft-store accident.

IN HER NEWEST novel, Katabasis, R. F. Kuang straps the mythic baggage of Dante and Orpheus onto two graduate students, Alice Law and Peter Murdoch. After accidentally killing their tyrannical professor, Grimes, the two sneak into hell to resurrect him. What they find there is barely distinguishable from their graduate studies. Kuang’s underworld is no cartoon inferno; it is a chilling landscape of extreme isolation, where the circles of punishment are the final expressions of the sins that isolate us in life.

The world of Katabasis (meaning “journey to the underworld”) is nearly identical to our own, save that magic is real. It has been institutionalized and is studied at the world’s premier universities. Grimes rules the Magick school at Cambridge with an iron fist, his abusive behavior excused as a function of his genius (and the price graduate students must pay for success). Alice and Peter are Grimes’ current star students, but this makes them more subject to his tyranny, not less. Alice “was of course underpaid and overworked, but this condition was common among graduate students and no one cared much about it,” Kuang writes. Neither Alice nor Peter (“the nicest guy in the world … who always holds you firm at arm’s length”) can see their suffering for what it is: a deluded isolation so complete that even hell seems preferable.

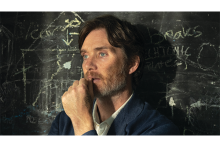

Teachers’ Mounting Pressure

The tight, gritty drama Steve offers an intimate look at a last-chance reform school in the 1990s. As determined head teacher Steve (Cillian Murphy) slowly unravels, we are reminded that we can’t take care of others until we take care of ourselves. Netflix

EARLY JANUARY MARKS the start of the season of Epiphany, during which Christians recognize the beginning of Jesus’ ministry. Scriptures point to the disruptive nature of Christ’s messiahship: Jesus asks John to baptize him (Matthew 3:13-17), an act that surprises John, who believes he’s unfit to baptize the son of God. Then Jesus delivers his first miracle when he turns water not just into wine, but the best wine, upsetting the tradition of serving good wine first, and cheap wine later (John 2:1-12).

Both acts signal that Jesus’ ministry won’t be what people expect. Rules will be challenged. Abundance, not scarcity, will reign. These stories remind us to seek the living God in unexpected forms.

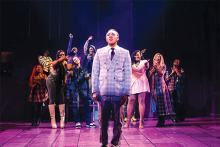

EARLY IN THE musical Saturday Church, the endearing teenage protagonist Ulysses prays to God. His father has died, his mother is always working, and his church community keeps pushing him to be less effeminate. “I’m in here, a prisoner of all my thoughts,” Ulysses sings. “Can anybody help?”

Onto the stage—wearing a long wig, a shimmering dress, and knee-length boots—steps “Black Jesus.” “Are there any queens in the house?” they sing to the room, before proceeding to do a dance number in the style of queer Black and Latino ball culture. “I come in many forms,” they tell Ulysses. “But this is my favorite.”

Black Jesus is one of several biblically inspired characters and events to have recently debuted in new musicals in New York. And while their plots vary widely, each has mined the Bible in ways that offer fresh resources for the Christian imagination.

PUERTO RICAN MUSIC star Bad Bunny had quite the run this past year. In September, he was announced as the headliner of the Super Bowl LX halftime show. In October, Billboard recognized him as the top Latin artist of the 21st century. All of this was on the heels of his 31-concert residency on the island of Puerto Rico. The residency infused close to $400 million into the Puerto Rican economy, centering, and, for many, revealing the music and culture of Puerto Rico.

The act of revealing the beauty of humanity and culture is very much tied to the Christian season of Epiphany. Many Christians consider this season to mark the revelation of God enfleshed, encultured, and embedded in time and place. God chose to participate in human life in a little-known territory occupied by the Roman Empire. In choosing the obscure village of Nazareth, the Divine presence signified that Love, in the world, begins at the margins.

For five years now, Sojourners has created a list of our favorite films of the year. And because we’re Sojourners and not Vulture or IndieWire, our list follows a different set of priorities. We only focus on films that are concerned with spirituality or justice (or when we’re really lucky, both).

This year, more than any of the other four years we’ve done this round-up, I was struck by the sheer number of films grappling with faith and justice.

The most powerful moment in Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery isn’t a murder or a big reveal. It’s a phone call.

Father Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor) is trying to help solve the murder of the controversial head priest of his small-town parish, Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin). Standing in the rectory with private detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig), Jud calls a records office to request information related to the case. The clerk, Louise (Bridget Everett), is overly chatty, much to Father Jud’s annoyance. It seems like she’ll never shut up. But it turns out she, too, has a request. After a few minutes, Louise stops talking to ask, “Father, would you pray for me?”

What if Jesus used his omnipotence not only to curse barren fig trees but also to kill those who annoyed him?

That’s a premise director Lotfy Nathan explores in The Carpenter’s Son. The supernatural horror film imagines Mary, Joseph, and Jesus’ time in Egyptian exile after they flee King Herod (though curiously, none of the characters in the film are directly called by those names). Nicolas Cage plays the Carpenter, who, along with the Mother (FKA twigs), tries to protect their son (played by Noah Jupe, credited only as The Boy) from the suspicious townspeople around him. The Boy’s miracles are awe-inspiring, but they’re also terrifying: In one sequence, he pulls a snake out of a woman’s mouth. While the Carpenter and Mother try to control the Boy’s power, they’re not able to stop his wanderings. Eventually, his curiosities lead him to a devil figure—a character known only as the Stranger (Isla Johnston), who tries to use his powers for her own ends.

On the cover art of her latest album, Lux, Spanish superstar Rosalía poses in a white nun’s habit, arms bundled to suggest straight-jacket confinement or maybe self-love. Before anyone heard a note of the new music, the internet was already bubbling over with commentary, par for the course when it comes to the complicated pop auteur. Fans and haters alike wondered what the Catholic imagery might mean. Habit aside, had Rosalía gone tradwife? Even Ikea joined in on the pre-release conversation, posting a version of the album cover with an overhead lamp. In Latin, Lux means light.

The album is a visionary landmark in pop music. Largely departing from previous forays into flamenco fusion and experimental reggaeton, Rosalía primarily draws from the classical tradition for the project, recording with the London Symphony Orchestra and pushing her voice into new operatic territory. Oh, and she sings in 13 different languages.

The most terrifying thing about power isn’t the force it applies; it’s the moral vacuum it creates in the soul of the person wielding it.

I think of the times I’ve made choices that were professionally powerful but ethically hollow—the quick decision that saved time but neglected a vulnerable party, the project that elevated my status but buried someone else’s contribution. We’ve all been Victor Frankenstein, playing God with a Promethean flame, only to be horrified when the fire scorches someone else.

In early 2024, filmmaker Sepideh Farsi felt compelled to document life in Gaza. Ultimately, she couldn’t gain access to the Strip, but she connected with a photographer who’d lived all 25 years of her life there: Fatma Hassona.

The documentary Put Your Soul On Your Hand and Walk is almost entirely composed of their monthslong correspondence. Farsi weaves Hassona’s portraits of an increasingly battered Gaza between a steady exchange of audio messages, spotty video calls, and text messages.

WHEN THE VATICAN introduced an anime-inspired mascot named Luce for the Year of Jubilee, online critics called it creepy, uninspiring, even “deeply evil.” The pushback against the cheerful, blue-haired pilgrim isn’t that surprising given the way anime is often stereotyped as an immature medium. Yet as animator-director Naoko Yamada demonstrates in her latest film, The Colors Within, anime can convey important existential truths.

Anime (Japanese animation) originated in the 1900s and spread across the globe with the advent of the internet and streaming services. Signature attributes of anime—including big-eyed characters with vibrant hairstyles—attract interest and, occasionally, scorn. Yet Japanese studios like Studio Ghibli have done well to engage with serious topics, from fascism to the devastations of war. Yamada’s work gives us another reason to take this medium seriously.

A FEW SUNDAYS ago, my partner Greg and I made a pot of chili for our community’s weekly dinner. The New York Times recipe said to add orange juice to the chili, letting it simmer and froth among the chopped onion, garlic, and butter. Then we mixed in the thick, tangy sauce from adobo chili peppers with black beans and sweet potatoes and corn, zipped with lime juice. It was rich, spicy, generous—brightened with the sun.

Lately I’ve had fun trying to write about food, playing with how I’d describe a certain taste, smell, or texture. I’ve been inspired by reading M.F.K. Fisher, who wrote essays about food starting in the late 1930s. She wrote gorgeous prose embedded with care for the human heart, for its loneliness and sadness and hope. In her 1937 essay “Borderland,” she writes about how each of us has our own private food pleasure—hers was warming sections of a tangerine on a radiator in the winter, which she describes while watching soldiers in Strasbourg march along the Rhine, the horrors of war closing in.

More Than Sobriety

The documentary A Bridge to Life profiles a residential program in rural Virginia for men overcoming addiction; founder and pastor William Washington believes environment is key to sobriety. By centering structure, job training, and hope, the program boasts a 5% recidivism rate. PBS