Yanan (he/him) is a writer from the Philippines who serves as editorial director at the Center for Barth Studies, where he guides initiatives that examine Christian faith and practice through the lens of progressive politics. He holds a master of divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary and produces house music in his spare time. Find him on Instagram: @yananrahim.

Posts By This Author

Mary Casts Down Pete Hegseth’s False God

I remember the first time I asked Mary to pray for me. It was at the height of the George Floyd protests in June 2020.

I Came to the U.S. a Capitalist, Now I Support Mamdani

When President Donald Trump and New York Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani first met back in November, I had to laugh. Partially because there is something deeply absurd about these two men—Mamdani, a self-proclaimed Democratic Socialist, and Trump, who once proclaimed he wished to be a dictator for “one day”—smiling and posing for photos in the Oval Office. But I mainly found myself laughing because, despite the drastic differences between these two politicians, both have been critical to my own faith and political journey.

What Jesus Teaches About Those Who Let Kids Go Hungry

This past weekend, funds for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program ran out due to the longest government shutdown in U.S. history. But after two federal judges ruled that the Trump administration could not legally prevent the nation’s largest anti-hunger program from receiving funds, the administration said it would designate $4.65 billion from an Agriculture Department contingency fund to offer partial relief to the 42 million people who rely on SNAP benefits.

The Christian Case for Open Borders

A federal judge has ordered the closure of the notorious immigration detention center known as “Alligator Alcatraz,” citing environmental violations and opposition from the Miccosukee Tribe. Progressives are celebrating this as a significant triumph for Florida’s Everglades, Indigenous communities, and the migrants who have endured the detention center’s conditions. But is this court ruling truly the sweeping victory that advocates claim?

Charlie Kirk Deserved the Life He Callously Denied Others

I read the news, stepped into my car, and let out a guttural scream.

Charlie Kirk, 31, had been shot and killed while speaking at Utah Valley University.

Can Global Evangelicalism Save American Evangelicals From MAGA?

In many headlines and on social media, the term “evangelical” is often conflated with “conservative,” “white,” “male,” and “American.” Many in the U.S. evangelical community are resisting that conflation, actively pushing for a new vision for evangelicalism that situates it within a global landscape. For these evangelicals, the future of evangelicalism is less James Dobson and more Botrus Mansour.

As such, Christianity Today often uplifts the multicultural face of global evangelicalism, suggesting that decentering the white American experience offers a new path forward for evangelicalism. Hence, the oft spoken refrain: The new face of Christianity is not a white man, but a woman in Africa.

5 Imperatives for Seminaries Under Authoritarianism

Immigrants are being disappeared. Journalists are being threatened. Protesters are being criminalized. The poor are abandoned. The sick are left behind. Wars still rage. Democracy is crumbling.

The world feels increasingly precarious, and various crises are compounding and multiplying. What moral responsibility do religious institutions—especially seminaries—have at this time?

Zohran Mamdani Is Busting a Myth Many Christians Still Believe

When Democratic Socialist Zohran Mamdani defeated Andrew Cuomo in New York City’s mayoral primary, the political establishment didn’t quite know what to do.

Headlines described Mamdani’s win as “stunning,” “electrifying,” an “upset,” and even a “miracle.” Right-wing critics responded with predictable vitriol, labeling Mamdani a “communist,” “terrorist,” and a “little Muhammad.” These attacks were aimed both at his politics and his identity as an Indian American, a Muslim, and a socialist.

But what was most remarkable about Mamdani’s successful campaign wasn’t necessarily Mamdani himself. Rather, it was the working-class support behind his campaign that captured people’s attention.

Superman, the Immigrant, Has Always Reminded Me of Jesus

Superman has always reminded me of Jesus.

In director James Gunn’s latest interpretation, Superman, Clark Kent is once again the heroic savior — thrust into battles against villainous forces and multi-dimensional threats. But this time, the stakes are political.

Can Kendrick Lamar Be a Prophet — and Be Rich?

Kendrick Lamar is a prophet — and a multimillionaire. Through his music, he tells the stories of the oppressed and marginalized, even as his own net worth surpasses $140 million. He calls for spiritual and political resistance to empire yet stood center stage at the Super Bowl halftime show — America’s most-watched spectacle of capitalist excess. At the end of it, he delivered a moment of rebellion, urging viewers to “turn the TV off,” subverting the very platform that elevated him. And yet, the performance also propelled his music sales and deepened his entrenchment within the industry’s elite. At a sold-out Pop Out show, he brought together feuding Bloods and Crips in a powerful gesture of peace and unity — sponsored, ironically, by Amazon, a corporation widely criticized for its union-busting, exploitative labor practices, and surveillance capitalism.

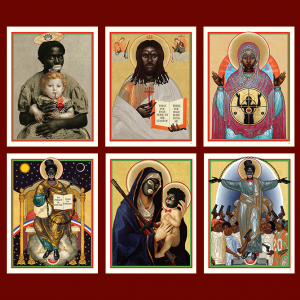

‘The N-Word of God’ Subverts Racist Iconography

As racist ideas continue to plague U.S. politics, Mark Doox’s Afro-surrealist and satirical graphic novel, The N-Word of God, couldn’t have arrived at a better time.

The book is a visual novel told through depictions of anti-Black images — Black people eating watermelons, Jim Crow caricatures, mammies, and blackface — all stylized in the form of Eastern Christian iconography. This is a style that Doox has termed “Byzantine Dadaism.” Doox’s novel deconstructively takes these caricatures that have historically harmed Black people and reimagines them as symbols of Black resilience and healing, restoring the inherent dignity that belongs to every human being, especially those who have been racialized and subjugated by U.S. anti-Blackness.

Black Religion Thrives on Difference

J. Kameron Carter explores the disruptive, poetic practice of Black religion.

ON APRIL 13, 2023, Ralph Yarl, a Black 16-year-old in Kansas City, Mo., went to pick up his younger siblings from a friend’s house. Mixing up the address, Yarl accidentally knocked on the door of an 84-year-old white man, Andrew D. Lester, who reacted by shooting Yarl in the head and then in the arm. Police took Lester into custody, only to release him without charges in less than two hours. As a result, protesters marched in Lester’s neighborhood, calling for his arrest. After days of protest, Lester was apprehended. In court, he pleaded not guilty, saying that he shot Yarl twice because he was “scared to death.” Yarl was in the hospital for three days before returning home to recover. In response to the shooting, Kansas City Mayor Quinton Lucas, who is Black, lamented, “You’ve heard about driving while Black ... Can you not knock on the door while Black? It’s almost like you can’t exist.”

In The Anarchy of Black Religion: A Mystic Song, J. Kameron Carter, a scholar of religion, English, gender, and African American studies, frames the current reality of modern Black suffering as “antiblackness,” or in his own words, “the settler colonial antiblackness of the religion of whiteness.” For Carter, antiblackness is the performance of a racial liturgy. This may sound strange to some readers — how can racism be religious, or liturgical? But what Carter is getting at is that there is a pattern — a ritual — to white violence against Black people. Lester’s shooting of Yarl was just one incident of this racial liturgy playing out. The murder of Jordan Neely by Daniel Penny in a New York subway car is another. They are all sacrifices on the altar of whiteness.

The Gospel Belongs to the ‘Heathen,’ Not White Saviors

In current times, the idea of the heathen underpins “a White American Christian superiority complex.” Lum explores this through the white savior trope, pointing to the historical example of how many white Americans positioned themselves “in opposition to the heathen world… [in order] to give themselves a venue for the evangelizing work that marked them as the givers [rather] than recipients of aid.” Within the context of the United States, “heathen” has become a racial and classist designation meant to distinguish between the so-called “first world” and the “third world.”

Four Things to Know About Going to Seminary

We are students of theology. One of us (Amar) has just recently graduated from Princeton Theological Seminary. The other one of us (Yanan) is currently in his first year at Princeton Theological Seminary. Bringing our perspectives together, we hope to offer advice for seminarians from two sides — beginning and end — of the degree program.

Nine Bible Verses About Indigenous People and Land Rights

If God tends to the lilies of the field, how much more will God protect the poor and oppressed (Matthew 6:25-34)? This is the correct definition of divine providence: God cares for, loves, and empathizes with the meek who will one day inherit the earth. This is the providence that theologian James H. Cone imagined in his seminal work God of the Oppressed: “God has not ever, no not ever, left the oppressed alone in struggle. He was with them in Pharaoh’s Egypt, is with them in America, Africa, and Latin America, and will come in the end of time to consummate fully their human freedom.”

My Country Is Ravaged By Typhoons; the U.S. Military Is Responsible

Due to climate change, people — entire tribes and cultures — are losing their homes and are being displaced from their lands. Indeed, the United States military needs to be held accountable for polluting the planet. For example, if preventive measures and legislation like the Green New Deal are not enacted to curb U.S. imperialism, more Indigenous peoples will perish due to climate disasters.

My Lola Is Decolonizing the Garden of Eden

Even in the midst of our lands groaning for their future restoration (Romans 8:22), the body of Christ dismantles the colonial systems that have privatized God’s creation. For in Christ, land and resources are not meant to be segregated but rather shared through hospitality for the flourishing of local communities, especially for the vulnerable and oppressed among us (1 John 3:17-18). In this way, Christ’s body is a new ecology between all lands, nations, and peoples through a common love for each other.