Interview

One of the stranger moviegoing experiences of my life was walking out from The Last Jedi and feeling sure I’d experienced a masterpiece. I’m not the most devoted Star Wars fan, but I thought I’d seen something special. I still do. So, you can imagine my surprise when the rest of the world was, shall we say, a little divided on The Last Jedi.

I’m not here to relitigate that whole exhausting conversation now. But while watching that movie, I felt a connection to the filmmaker, Rian Johnson. Something in the way he navigated the power of belief, the handing down of received wisdom, and the challenges of carving new paths in old traditions spoke to me. I was not surprised to later learn that Johnson had been raised in the church, and I was delighted when he decided to take that as both the theme and setting of the third Knives Out film, his wildly popular murder mystery franchise starring Daniel Craig’s Foghorn Leghorn-throated detective Benoit Blanc.

The most powerful moment in Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery isn’t a murder or a big reveal. It’s a phone call.

Father Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor) is trying to help solve the murder of the controversial head priest of his small-town parish, Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin). Standing in the rectory with private detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig), Jud calls a records office to request information related to the case. The clerk, Louise (Bridget Everett), is overly chatty, much to Father Jud’s annoyance. It seems like she’ll never shut up. But it turns out she, too, has a request. After a few minutes, Louise stops talking to ask, “Father, would you pray for me?”

As the longest government shutdown in U.S. history draws to a close, much of the news cycle has centered on the struggles of 42 million Americans missing benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

While benefits remain delayed, many of those 42 million may have spent more than a week unsure of how to pay for groceries. It’s difficult to grasp such a large number. For those without direct connections to food insecurity, the issue can remain hypothetical and far off.

Terence Lester, founder and executive director of the nonprofit Love Beyond Walls, is used to serving those our political system forgets. Love Beyond Walls is a nonprofit focused on poverty and homelessness, based the Atlanta suburb of College Park, Ga. The organization has partnered with local school districts to convert unused classroom space into resource centers designed to make sure students in poverty can get their basic needs met at school. It also provides hygiene stations for people experiencing homelessness throughout the city.

The sidewalk outside of a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement processing facility in Broadview, Ill., seems like an unusual place for an altar call, but that is where Rev. David Black of The First Presbyterian Church of Chicago felt moved to pray and invite ICE agents to repentance.

Since President Donald Trump launched a campaign of mass arrests and deportations in the Chicago area in September, many clergy, faith leaders, and concerned neighbors have been showing up to sing, pray, chant, lead communion, and bear witness in solidarity with people in their community who are being separated from their families, detained, deported, traumatized and forced into hiding. On Sept. 19, Black was on the sidewalk praying for ICE agents and detainees in Broadview when he and other protestors were met with violence. A Chicago Sun Times photo by Ashlee Rezin captured the moment masked ICE agents sprayed Black in the face with chemical irritants. As the image spread on social media, many people commented that the image seemed destined for history books—while others worried about whether the future will have history books.

As I write, the federal government remains shut down, and with it, the Smithsonian and its numerous museums.

I suspect, however, that many in the executive branch aren’t losing sleep over a lack of access to publicly funded, rich, beautiful histories ranging from natural sciences to African American history. In the past year, the Trump administration has demanded those museums shape their presentation to his preferences, cut funding to these institutions, and lambasted the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in particular.

Amid these attacks on a truthful telling of history, I spoke to Harry Singleton III, the faith-based director of the International African American Museum, to understand how a liberation theologian approaches the task of museum work. Singleton is the son of a Baptist minister; a native of South Carolina, where the museum is located; and a scholar who spent most of his time in academia before transitioning to the museum in June.

For as long as Lecrae has been a public figure, he has been a lightning rod for white evangelical racism.

A spearhead for the movement that turned Christian hip-hop from a misfit genre to a powerhouse industry, Lecrae has consistently endured racism thinly veiled as theological critique. While he was earning deep respect from hip-hop luminaries—Sway In the Morning and Kendrick Lamar, for example—he was fighting a Christian industry that only begrudgingly came to accept that CHH was here to stay.

Early on, critics claimed “Christian” and “hip-hop” were contradictory terms, and Christian rappers like Lecrae were putting godly messages second to godless culture. Then, as the U.S. began another reckoning with racist police violence, Lecrae was accused of division, partisanship, and putting “political issues” like racism before “biblical issues” like abortion. When he attempted dialogue, white pastors told him to his face that chattel slavery was a “white blessing.”

This interview is part of The Reconstruct, a weekly newsletter from Sojourners. In a world where so much needs to change, Mitchell Atencio and Josiah R. Daniels interview people who have faith in a new future and are working toward repair. Subscribe here.

I’m not on TikTok, so I’d never heard of 22-year-old content creator, Taylor Cassidy. Cassidy rose to prominence after she started creating engaging and easily digestible videos about Black history. During my interview with Cassidy, she told me her goal is to make sure her audience feels uplifted and excited about learning.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has estimated that since Israel’s war with Gaza began in October 2023, Israel has killed 235 journalists and imprisoned another 86. According to CPJ, this has been the deadliest period for journalists since they first began collecting data in 1992.

When Robert Redford was 18 years old, his mother died—suddenly and young—following complications from delivering twin girls who did not live long. This harrowing loss left young Redford disillusioned with God. “I’d had religion pushed on me since I was a kid,” he would tell Michael Feeney Callan, his biographer. “But after Mom died, I felt betrayed by God.”

I've grown tired of this question: “How do we get young people to come to church?”

Yes, I know that 49% of Americans born in the 1940s or earlier attend religious services at least once a month. And yes, I know that when it comes to my ilk, people born in the 1990s or 2000s, that percentage cuts in half. Those numbers don’t scare me.

This interview is part of The Reconstruct, a weekly newsletter from Sojourners. In a world where so much needs to change, Mitchell Atencio and Josiah R. Daniels interview people who have faith in a new future and are working toward repair. Subscribe here.

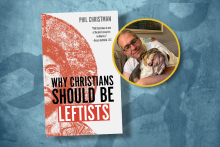

I’m going to let you in on a little secret: If you see a book about politics published in 2025, it’s very possible the world is different than what the author hoped for when they pitched it.

Aymann Ismail has a variety of identities that keep him busy. When I asked him to tell me about himself, he replied, “I’m a journalist, a parent, and a full-time Arab American.” He is also the author of the new memoir, Becoming Baba: Fatherhood, Faith, and Finding Meaning in America.

One of the things I appreciate most about Ismail, who is Muslim, is the way he subtly incorporates reflections on his faith into his writing. In Becoming Baba, Ismail relates how he sat down to read the Quran, only to vehemently disagree with what he read. This led him to explore his doubts and questions, which Becoming Baba explores in an engaging and refreshing way.

Full disclosure: It’s entirely possible you wouldn’t be reading this interview right now if not for its subject. Let me explain.

In 2013, Jemar Tisby and Phillip Holmes, co-founder of the organization then known as the Reformed African American Network, started a podcast called Pass the Mic.

As an editor and journalist, it’s my job to have words for the news of the day. But now and then, the news of the day has a way of robbing me of all my words. This is especially the case when the news of the day revolves around an injustice that is actively harming our world and humanity. What truly leaves me wordless is when we, as people, know that something catastrophic is happening, but we seek to minimize or ignore it. How do I change that? Is there a perfect combination of words and data to prevent that?

A specific example is Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza. I’m not sure what else has to be said at this point to help people realize that a genocide is happening right before our very eyes, and it is likely to expand beyond Gaza into the occupied territory of the West Bank. One of Israel’s leading human rights organizations—B’Tselem—is desperately trying to raise the alarm about this very fact.

Recently, I saw a clip that claimed to show video game players performing the “first Fortnite baptism.”

Fortnite, for those unfamiliar, is an online battle royale-style game that boasts over a million active players. At its peak, it claimed over 14 million players. In the video, two characters, standing in a virtual lake exchange the questions: “Do you confess that Jesus is your Lord and Savior?” “Will you follow him for the rest of your days?” Followed by a Trinitarian baptism, and exclamations of “Let’s goooooo!”

As I watched this theologically questionable exchange, I started thinking about Riley MacLeod. MacLeod is editor and co-owner of Aftermath, a worker-owned publication dedicated to games journalism and blogging. But I also knew MacLeod was a graduate of Harvard Divinity School and someone broadly interested in faith and social justice.

Despite what you may have heard about a “muted” response to President Donald Trump’s second term, the size and scope of protests in 2025 have far surpassed what we saw in 2017.

According to data compiled by Harvard political scientist Erica Chenoweth and researchers at the Crowd Counting Consortium, the vast majority of these protests have been nonviolent; in April and May — which included large nationwide protests like Hands Off!, No Kings, and May Day — 99.5% of the protests featured “no injuries, arrests or property damage.”

Brad Onishi is the co-host of a podcast titled Straight White American Jesus. With co-host Daniel Miller, Onishi examines and deconstructs evangelical politics, theology, and culture. Onishi, who has a doctorate in religious studies, told me that when they began the podcast in 2018, he wasn’t sure if anyone would listen. But now, almost 900 episodes later, they’ve “commented on every angle and every aspect of Christian nationalism, the Trump presidencies, the Biden presidency, and everything in between: from gender to race, sexuality, church politics, and so on.”

You can add Nathan Evans Fox to the list of artists who are in the country music scene without entirely being of it. Or maybe it’s better to say Fox is operating in a purer, livelier stratosphere of country music that neither needs nor wants the approval of the Nashville ruling class. So far, he’s doing just fine. His “Hillbilly Hymn (Okra and Cigarettes)” made a viral splash; a rich tune in the tradition of old Appalachian spirituals that envisions a cop-free Heaven where “the rich get scared” and “the guns are all for shootin’ clays.”

Some may want me to stay quiet, but I want to be loud. I want to scream. I want to cry. I want to embrace the full spectrum of my humanity, the same way that author Austin Channing Brown has learned to embrace herself. In her upcoming book, Full of Myself: Black Womanhood and the Journey to Self-Possession, she details this journey.

Most would agree with the Nigerian-British singer-songwriter Sade that we don’t need any more war, but we are in desperate need of just a little peace. So, what do we do when it becomes clear that the people advocating for that peace are being thrown in prison or portrayed as “terrorists” who are interfering with the “peace process” in the Middle East due to their advocacy for Palestinian human rights?

Mohsen Mahdawi, who is a legal permanent resident in the U.S., was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents on April 14 as he exited his citizenship interview at a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services office in Vermont. President Donald Trump’s administration accused Mahdawi of potentially undermining the peace process in the Middle East. But despite this accusation, the government has not charged Mahdawi with a crime. Mahdawi was released from detention on April 30 after U.S. District Judge Geoffrey Crawford granted him bail, commenting that Mahdawi had “made substantial claims that his detention was in retaliation for his protected speech.”