Arts & Culture

I FIRST CAME across digital media artist Madeleine Jubilee Saito’s work on social media. While scrolling through a sea of Instagram stories about environmental disasters, civil unrest, and humanitarian strife, I reached a square that made me pause: a multicolor four-panel image from a digital watercolor comic. I took in the top two panels of a gray figure staring out into the sky and then the glimmering, fruited foliage framing the bottom two panels. It felt like a vision from a better, more just future. The text on each panel, though brief, was powerful. I took in each word like a sacred telegram: THE GREAT WOUND / IS HEALED / ALL THINGS / MADE NEW.”

When I was younger, I found comfort in dynamic plotlines nestled in the predictable geometry of print and online comic series. Through Saito’s work, that comfort returned to me, in the form of four panels grappling with climate grief and environmental repair.

When I spoke with Saito about her work, she said that her affinity for comics started in high school. “As a young person, I had a very hard time accessing my own feelings or seeing that my interiority or my life were particularly valuable,” she said. “Comics were a way I could crystallize that value and the meaning of my own interiority for others — make it visible.” Now, Saito’s work conveys the value of the natural world. In her ecological storytelling, we see portraits of people amid towering trees and shimmering waterways. Her human subjects submerge themselves in the elements; her natural subjects invite readers to take a closer look at this numinous world.

Her upbringing in northern Illinois exposed Saito to the tensions between humans and earth. She grew up in a house deep in the woods — “a strip of forest in the middle of this desolate monocrop landscape,” she said, explaining how she saw beauty amid exploitation. “The animals — raccoons and possums — were pests to be managed. Every year the trees and bushes and plants from the forest would encroach further toward the house and every year they would need to be cut back.”

This awareness of the adversarial relationship with the natural world has guided her work and now culminates in her debut book, You Are a Sacred Place: Visual Poems for Living in Climate Crisis (Andrews McMeel, 2025). The first section explores the doom happening parallel to climate collapse. In one story, we see someone curled up in bed, sinking into and verbalizing their sadness post-job layoff. Wildfire smoke chokes the Seattle air around them. In this panel, I see myself, two years ago, numb from financial despair while wildfire smoke cast a noxious orange hue over Philadelphia.

Meta's new "Llama 3" AI model was trained on the stolen text of poetry, sociology, fiction, theology, and more from countless writers, including a few who have written for Sojourners. Now, those writers are speaking out.

In Nosferatu, writer-director Robert Eggers seeks to empower Ellen as a martyr: Yes, her death is a tragedy. But by giving her agency in a world that sought to deny her humanity, Ellen is a savior, one who has laid down her life for her loved ones and for the world. The Christian parallels are obvious.

In ‘Christ in the Rubble,’ Palestinian pastor Rev. Munther Isaac surveys the devastation of his homeland and finds God in the most unexpected places.

Similar to Parasite, Mickey 17 is ultimately about the ethics of revolutionary struggle. The film considers how Christian morality — especially as understood by thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche, Michel Foucault, or Karl Marx, the latter of whom famously referred to religion as the “opiate” of the masses — prevents the downtrodden from standing up for their rights. Here, Pattinson’s Mickey is a clear stand-in for Christ and the model Christian. Resurrected ad infinitum, he humbly accepts the pain, suffering, and dehumanization inflicted on him by his apathetic, at times downright demonic coworkers as punishment for his perceived sins.

FARMER AND WRITER Wendell Berry has reminded us for decades that eating is an agricultural act, a daily, sacred practice that connects us to the land and people who produce our food. But given the story Austin Frerick tells in Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry, it’s fair to say eating is now an industrial act.

Frerick, an expert on agricultural and antitrust policy, grew up helping his grandparents farm near Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He watched dramatic changes in the state’s landscape over time: Corn and soybeans replaced diverse crops. Pigs and cows disappeared. Family farms and the local businesses that supported them faded away, replaced by industrial-scale farms.

Frerick looked for answers and found a handful of tycoons driving these changes across the U.S. He profiles seven of them, showing how their corporate monopolies have transformed every aspect of our food system.

Jeff and Deb Hansen are the hog barons. The Iowa couple has built an empire of hog confinement facilities, warehouses in which thousands of hogs are packed until ready for slaughter. It’s more profitable for meatpackers to buy these hogs than those from family farms, which has put thousands of small farmers out of business. Frerick writes that since the Hansens started their company in 1992, “the state’s pig population has increased by more than 50 percent while the number of hog farms has declined by over 80 percent.”

Our Lord Jesus Christ could often be found on a mountain. He went to a mountain to pray, to seek solitude from the crowds. He fasted and prayed for 40 days and 40 nights on the mountain where the devil tempted him. He met Moses and Elijah on Mount Tabor and was transfigured before his disciples. His most famous sermon is the Sermon on the Mount.

SINCE ITS PREMIERE in late 2023, Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days — a quiet, contemplative film about a janitor who cleans Tokyo’s public toilets — has been showered with accolades, including a Cannes Film Festival Palm d’Or nomination, an Oscar nomination for Best International Feature, two Japan Academy Film awards for Best Director (Wenders) and Actor (Kōji Yakusho), and even an Ecumenical Jury Prize, an independent award created by international Christian media organizations SIGNIS and Interfilm.

All these honors more or less speak for themselves, except — perhaps — the last one. Perfect Days is, after all, neither a Christian film nor an explicitly religious one. Except for the occasional reference to concepts related to Buddhism, such as meditation, karma, and nirvana, the only time protagonist Hirayama seems to make contact with some sort of higher power is when he listens to Nina Simone’s “Feeling Good” on his way to work each morning.

Fortunately for Wenders, Ecumenical Juries — which attend film festivals across the world — don’t limit themselves to the likes of Jesus Christ Superstar or The Passion of the Christ. At least, not anymore. “Initially, the focus was on films reflecting the Christian worldview,” says S. Brent Plate, a professor of religious studies at Hamilton College in New York, longtime Ecumenical Jury member, and author of Religion and Film: Cinema and the Re-creation of the World. “Over time, we shifted toward a broader interpretation of that focus, looking for films that, even if they don’t directly address religion, promote humanistic, progressive values.”

As a result of this shift, the Ecumenical Jury’s mission has come to raise worthwhile questions for film aficionados and religious scholars alike: Can movies function as a mode of religious instruction, bringing us closer to the divine the way a sermon might? Can they teach us how to be better people, inspiring us to lead more fulfilling lives by untangling the mysteries of the human condition? And, most important perhaps, can they nourish our spirit, impart morality, and help us overcome moments of personal crises in an age where the historical provider of such services in the West — the church — is losing its longstanding influence?

At the first of what will be many funerals that appear in The Monkey, a young priest struggles to find the right words. After offering some half-hearted bromides about how everything happens for a reason, the priest can no longer pretend that there’s some divine plan behind the death that brought them together — an accident involving a hibachi chef’s knife getting too close to a diner.

“It is what it is,” the priest (Nicco Del Rio) finally declares, with the most conviction he can muster. “The words of the Lord.”

Sunday, he emerges carrying blue iris,

lilies, and maidenhair ferns,

a few cabbage palm fronds,

shears closing their silent beaks

the light just disclosed behind the river hill,

boxwood and red peeled trunks of crepe myrtles.

He picks and chooses, gathers them in his arms,

he will push the iron gate and climb the serpentine brick path.

He pitched semi-pro baseball,

golfer, lifeguard, fencing master,

a life to the body, works of reflexes,

eyes of a blue cutting-edge, deft hands, perfect ambidextrous,

slant ball, whirled ball, knee ball. He catches all.

He embraces the flowers against his chest

and deposits them by the altar,

signs himself, arranges them in a white vase.

No ball to miss.

God and prayers, fragrant Easter between his two luminous hands.

I GREW UP heavily steeped in ’90s Christian rapture culture. I’d polished off all 40 books of the Left Behind kids series before I finished 6th grade, and holes formed in the knees of my favorite butterfly jeans because I wore them as often as I could to make sure I was raptured in them.

While the rapture is no longer central to my faith, I never realized how much apocalyptic thinking is soaked into our culture — and how much of it I absorb — until I picked up Dorian Lynskey’s latest book.

In Everything Must Go, Lynskey chronicles humanity’s unending preoccupation with the end, detailing how apocalyptic thinking has pervaded the media and pop culture throughout history, “turn[ing] fear into entertainment.” His book focuses on examples of apocalyptic thinking that “reveal something important ... about the times in which they were created.” Most obviously, apocalyptic imaginings reveal what we’re afraid of. Each era has had a different disaster to fear, be it nuclear, ecological, or cosmological. For millennia, the world has been ending again and again. “There is simply no end of ends,” Lynskey writes.

And some of the most influential end-time tales come from the Bible. From Genesis to Revelation, scripture is full of disaster narratives. “It is the Bible that supplies the primordial tales that surface over and over again in the art, literature, cinema, and television of the West,” Lynskey writes. “The Christian apocalypse is still with us, then, in a range of disguises.”

Queer Healing

Nate Peters and Susie Aguirre are Christians reconciling their faith and sexualities. The I Tried to Be Straight podcasters are reconstructing their faith on a firm foundation and bringing others along, including an ex-conversion therapist and a retired NFL player. Patreon

Mary Myths

Unmaking Mary, by Chine McDonald, challenges the idealized notion of mothering projected onto the Virgin Mary. Weaving her experiences as a mother with theological insight, McDonald dismantles impossible standards to offer a liberating and profoundly human vision of motherhood. Hodder & Stoughton

Redirecting Rage

In The Tears of Things, Richard Rohr explores how Jewish prophets transformed their rage into compassion, promoting empathy in our turbulent world. “Prophets and mystics recognize what most of us do not — that all things have tears and all things deserve tears,” he writes. Convergent

I’VE BEEN THINKING about the 1993 comedy Groundhog Day a lot since the beginning of the second Trump presidency. Like Bill Murray’s disgruntled TV weatherman Phil Connors, who’s forced to relive Feb. 2 on an unending loop, many of us feel like we’re reliving a nightmare. We find ourselves taking steps backward from progress we thought was permanent. Like Phil, we’re battling the feeling that no matter what we do, nothing will change.

However, being stuck in a moment you want to leave behind is only Groundhog Day’s setup, not its message. In a world where our individual actions don’t seem to change anything, Groundhog Day reminds me why helping others still matters.

When we meet Phil, he’s whining about making the annual trip from his station in Pittsburgh to Punxsutawney, Pa., to cover the groundhog festival. The trip is beneath him, he thinks. When a snowstorm strands Phil and the news team in Punxsutawney overnight, it seems like the ultimate insult — until Phil wakes up the next day and discovers he’s reliving events all over again. And again.

As a theologian, ethicist, professor, priest, and author, Gary Dorrien has helped shape and excavate the overlap between social justice and faith for nearly 50 years. He has written definitively as a historian and prophetically as an activist, all while teaching generations as a professor of religion. Now, he explains why it was time to tell his own story.

The U.S. has always considered itself as this New Jerusalem — a land specially blessed by God — but also one that is only available to those specially chosen. And from the establishment of the United States as a nation, as Lin discusses, this drive to only welcome certain individuals has been heavily focused on questions of race and national origin. The notion that the U.S. is a nation that welcomes immigrants is a myth that contradicts historical record. Instead, our “[i]mmigration and naturalization laws serve ultimately to create the ideal population as conceived by those who set policy and legislate,” Lin writes.

As Semler, Grace Baldridge has spent the past few years proving there was a space for people like her in the Contemporary Christian Music scene, even if she had to dig that space with her bare hands. Now, with the release of her debut album, she's looking back on how she did it — and what’s next.

James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown is a striking film. Centered on a young Bob Dylan (Timothée Chalamet), the biopic chronicles the folk music community that bounced in and around 1960s New York City, offering stellar musical and acting performances in the process. But its wisest scene takes place off stage in an intimate conversation between Dylan and Pete Seeger (Edward Norton).

Fear turns me into a tree.

Every pruning healed

becomes an eye.

Sunlight plays the leaves,

each a pool of green incandescence,

a window to the heart.

Every wound a hieroglyph.

Each whisper a new chord.

Come inside my radiant dream:

a phoenix fruit ripens unseen.

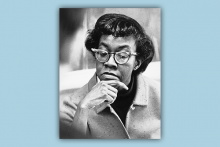

IN “KITCHENETTE BUILDING,” Gwendolyn Brooks, the first Black Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, considers the challenge of dreaming in grim places. The setting of this 1945 poem, published as part of Brooks’ first collection, A Street in Bronzeville, is the titular kitchenette building, a housing unit of many cramped, run-down apartments, often rented by Black residents in that era in cities like Chicago. Tenants are “grayed in, and gray,” worn out by systemic injustice and the demands of daily life, such as paying rent and putting food on the table. Still, the speaker — who speaks on the behalf of a collective “we” — wonders if a dream could rise “through onion fumes” and “sing an aria” in the building.

The dream in “kitchenette building” is delicate and “fluttering,” something that requires time and contemplation — luxuries that systemic oppression makes nearly impossible. Brooks’ biographer, Angela Jackson, in A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks, describes this poignantly: “Life is grim in these kitchenette buildings ... entrapment as in a prison. People here are not people; they are things, dehumanized by the nature of a system they did not volunteer for.” Later, she asserts that kitchenette residents “cannot even consider” a dream greater than a cold bath “[before] a realistic necessity comes up ... They take what they can get.”

Brooks makes it clear, though: Imagination is a vital precursor to liberation. “Kitchenette building” plants seeds in questions: What would happen if dreams of freedom and freshness had space to grow? What would liberation look like for Black communities and the U.S. as a whole?

Indie Imago Dei

In the title track of his new album, People Watching, indie rocker Sam Fender sees the face of God in the strangers he passes: “Envious of the glimmer of hope / Gives me a break from feeling alone / Gives me a moment out of the ego.” Polydor Records

Prophetic Dispatches

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This is a lament and rallying cry from Egyptian-Canadian journalist Omar El Akkad. With honest prose, he debunks American “fiction[s] of moral convenience,” including ideologies that fuel U.S. support of a genocide in Palestine. Knopf

Saints and Sinners

Characters in Jared Lemus’ debut collection, Guatemalan Rhapsody, are as broken and beautiful as their country. Among them are a band of thieving siblings, who justify their crimes by invoking Saint Dismas: “He stole because he had to ... and God forgave him.” Ecco