Abby Olcese (@abbyolcese) has been many things — a campus ministry leader at the University of Kansas, an English teacher in Prague, and an advertising assistant at Sojourners. These days, she’s a freelance writer based in Kansas.

Raised on a diet of Narnia, Bob Dylan records and Terry Gilliam movies, Abby is drawn to the weird, the nerdy, and the profoundly artsy corners of popular culture. She loves sharing this knowledge with others by writing about interesting new releases as well as lesser-known gems.

Abby is also passionate about the intersection of faith, social responsibility, and culture. She believes in the power of art to spark important conversations, inspire social change, and help people to better understand life in the kingdom of God.

When she’s not watching movies or writing things down, you can usually find Abby reading comic books or perusing the selection at her local record store.

Posts By This Author

‘Pluribus’ Turns Happiness Into a Virus, and Peace Into a Problem

If you ask TV writer and producer Vince Gilligan what his latest show, Pluribus, is about, he’ll turn the question right back around on you.

“I really like the idea of making a show and letting viewers tell us what it’s about,” Gilligan told Sojourners. “I don’t know that there’s any one answer to that question other than what the individual thinks.”

Watch This 1987 Film During Epiphany

Babette’s Feast shows how to seek the living God in unexpected forms.

EARLY JANUARY MARKS the start of the season of Epiphany, during which Christians recognize the beginning of Jesus’ ministry. Scriptures point to the disruptive nature of Christ’s messiahship: Jesus asks John to baptize him (Matthew 3:13-17), an act that surprises John, who believes he’s unfit to baptize the son of God. Then Jesus delivers his first miracle when he turns water not just into wine, but the best wine, upsetting the tradition of serving good wine first, and cheap wine later (John 2:1-12).

Both acts signal that Jesus’ ministry won’t be what people expect. Rules will be challenged. Abundance, not scarcity, will reign. These stories remind us to seek the living God in unexpected forms.

Sojourners’ Top Movies of 2025

For five years now, Sojourners has created a list of our favorite films of the year. And because we’re Sojourners and not Vulture or IndieWire, our list follows a different set of priorities. We only focus on films that are concerned with spirituality or justice (or when we’re really lucky, both).

This year, more than any of the other four years we’ve done this round-up, I was struck by the sheer number of films grappling with faith and justice.

‘Wake Up, Dead Man’ Takes Benoit Blanc to Church

The most powerful moment in Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery isn’t a murder or a big reveal. It’s a phone call.

Father Jud Duplenticy (Josh O’Connor) is trying to help solve the murder of the controversial head priest of his small-town parish, Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin). Standing in the rectory with private detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig), Jud calls a records office to request information related to the case. The clerk, Louise (Bridget Everett), is overly chatty, much to Father Jud’s annoyance. It seems like she’ll never shut up. But it turns out she, too, has a request. After a few minutes, Louise stops talking to ask, “Father, would you pray for me?”

What’s the Right Way to Tell the Story of a Killed Missionary?

Although Justin Lin is best known now for his work on the Fast & Furious (he’s directed five of the franchise’s 10 entries), he got his breakthrough in independent filmmaking with his 2002 crime drama Better Luck Tomorrow, about Asian-American teenagers in Orange County, Calif. Outside of the Fast franchise, the films Lin has directed and produced often focus on Asian and Asian American identity, exploring topics including generational divides and the pressure to achieve.

Those themes are also present in Lin’s latest film, Last Days, which marks his return to independent filmmaking. Last Days, in theaters now, is a drama about the life of John Allen Chau, the young missionary who was determined to make contact with the Sentinelese, an indigenous tribe living on a government-protected island off the coast of India, and one of the last uncontacted indigenous communities. Chau was killed by the Sentinelese shortly after his first encounter with them, leaving behind a story that generated ongoing conversations and debates about the ethics of international missions work. Chau’s story was also the subject of the 2023 documentary The Mission.

‘To Suffer Through Trauma Alone Is Unbearable’

The film ‘Sorry, Baby’ is the most accurate depiction I’ve seen of how trauma stays with you and what it takes to reach a place of stability.

IN A PERENNIALLY timely 2014 article about the lessons she learned from her experience with trauma, Catherine Woodiwiss wrote, “Trauma is a disfiguring, lonely time even when surrounded in love; to suffer through trauma alone is unbearable.” We need people around us when we’re suffering, if only to know that they’re there to call on when we need something.

When my trauma and anxiety journey started in 2016, I quickly learned that putting up a front of “Everything’s fine!” only made things worse. It was humbling to admit I needed support. It was empowering to realize people wanted to help. I knew that someday, when I felt better (and I would feel better), I would return the favor.

The film Sorry, Baby, from writer-director Eva Victor, is the most accurate depiction I’ve seen of how trauma stays in your mind and body and what it takes to reach a place of stability. After Victor’s character, Agnes, experiences sexual assault, she relies on the help of close friends and a neighbor, and a stranger’s kindness, to help her through the three-year period that follows.

Can TV Make You a Better Person?

‘Murderbot’: An unlikely example of how good storytelling helps us walk through the world.

I’VE SPENT MOST of my life explaining to people why movies and TV shows are more than just a way to pass time. My favorite screen stories — serial or cinematic — help me connect with their creators or the depicted characters. Narratives help us make sense of our experiences and recognize ways we can help others consider their own. Jesus knew this when he told parables, using stories to communicate some of his most important teachings on how we should live generously and faithfully.

A sci-fi series about a robot who struggles to relate to human beings may seem an unlikely example of how good storytelling helps us walk through the world. But that’s what the Apple TV+ show Murderbot offers.

‘The Life of Chuck’ Is Fearfully and Wonderfully Made

“Inside the soul of this accountant who loves his job and loves his wife and loves his son, is this dancer,” Hiddleston said during a press conference. “And that might be true of anyone you know or anyone you see on the street … Inside that human being is greater breadth and depth and range than we could possibly imagine.”

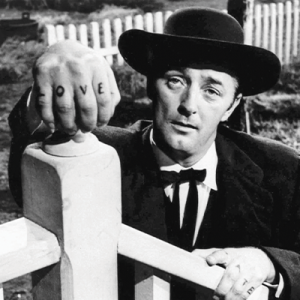

There Are No New Bullies Under the Sun

Why the 1955 film ‘The Night of the Hunter’ has only grown in influence during the last 70 years.

ECCLESIASTES 1:9 TELLS us “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done; there is nothing new under the sun.” I used to read that verse with a sense of existential fatigue, but as I’ve grown older, it reminds me that the struggles we face now are different forms of struggles as old as time itself. As hard as things might get, we’re never without hope that good will come back around, because it has before.

Examples of this exist in art as well as scripture. Take, for example, the 1955 film The Night of the Hunter, which addresses religious extremism, hypocrisy, and spiritual abuse. Director Charles Laughton’s dark and impressively modern approach to those ideas didn’t sit well with audiences at the time, but 70 years later, the film has only grown in influence.

Laughton’s film follows Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), a Depression-era preacher who funds his “ministry” by marrying widows and killing them for their money. We watch Powell court, manipulate, and murder a guilt-stricken woman, Willa (Shelley Winters). Willa’s children, John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) escape Harry’s clutches and find refuge with Rachel (Lillian Gish), a kind woman who helps them recover from their trauma.

Why I’ve Been Thinking a Lot About ‘Groundhog Day’ Recently

Phil Connors was forced to relive Feb. 2 on an endless loop. But the movie’s message is more hopeful than a recurring nightmare.

I’VE BEEN THINKING about the 1993 comedy Groundhog Day a lot since the beginning of the second Trump presidency. Like Bill Murray’s disgruntled TV weatherman Phil Connors, who’s forced to relive Feb. 2 on an unending loop, many of us feel like we’re reliving a nightmare. We find ourselves taking steps backward from progress we thought was permanent. Like Phil, we’re battling the feeling that no matter what we do, nothing will change.

However, being stuck in a moment you want to leave behind is only Groundhog Day’s setup, not its message. In a world where our individual actions don’t seem to change anything, Groundhog Day reminds me why helping others still matters.

When we meet Phil, he’s whining about making the annual trip from his station in Pittsburgh to Punxsutawney, Pa., to cover the groundhog festival. The trip is beneath him, he thinks. When a snowstorm strands Phil and the news team in Punxsutawney overnight, it seems like the ultimate insult — until Phil wakes up the next day and discovers he’s reliving events all over again. And again.

Director David Lynch’s Fascination with Sin and Redemption

Lynch, who died this month days before his 79th birthday, was fascinated by the coexistence of light and dark in the world, the effects of our sinful impulses on others, and what can happen when we pursue what’s right.

Refusing to Be Lost in Trauma

In ‘Nickel Boys,’ filmmaker RaMell Ross acknowledges injustice, abuse, and repeated heartbreak, but never dwells on it.

Trauma changes your memories. When I think of traumatic experiences in my life — what happened, how I felt before that moment, how I felt afterward, the changes I’ve noticed in myself since — they often play in short bursts. Those bursts are rarely sequential, and the length of time they last depends on how long I allow myself to linger on a memory.

Filmmaker RaMell Ross’ Nickel Boys, an adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s 2019 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, is a record of trauma. It tells the story of two Black boys’ experience at an abusive reform academy in Jim Crow-era Florida. The fictional Nickel Academy is inspired by an actual place, Florida’s Dozier School for Boys, where students received brutal treatment at the hands of staff. A 2012 investigation by the University of South Florida uncovered dozens of human burial sites on the property.

Ross does something unique with this story about trauma, memory, and how they relate to each other: He makes it feel authentic.

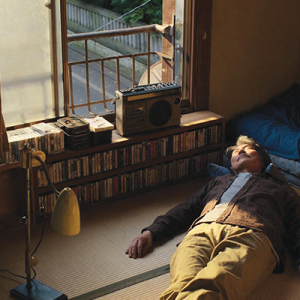

A Recent Trend: Movies About Presence

In a climate of overstimulation, these movies invite viewers to be still.

ONE WAY TO take a culture’s temperature at a given moment is to look at the art it produces. This is particularly true in film — a visual medium and a business largely driven by audiences’ perceived interests. Movies reflect their times, not just visually, but thematically.

Films made during the Great Depression, for example, included social realist dramas like Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow, about an elderly couple who lose their home to foreclosure, and works of optimistic patriotism like Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, where Jimmy Stewart brings his determined charm to Capitol Hill. Others, like Capra’s romantic comedy It Happened One Night, offered troubled moviegoers good-natured escapism.

So, what’s on our minds recently, cinematically speaking? Among other things, a pandemic, corrupt institutions, international tragedies, and (another) contentious election year. There are many reasons viewers might want to escape into simpler or more fantastical worlds.

One recent trend, however, has surprised me: movies about presence.

‘The Rings of Power’ Asks If You Can Save Middle-Earth Without Losing Your Soul

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power returned for its second season, bringing viewers back to a sprawling story inspired by the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Guardians of the Galaxy, 10 Years Later

The Marvel superhero movie’s true enduring appeal comes from its message about humility, selflessness, and community.

IN THE CLOSING scenes of Marvel’s original Guardians of the Galaxy, we find our heroes in a tight spot. The group — escaped science experiment Rocket Racoon, giant sentient tree Groot, assassin Gamora, ex-convict Drax, and mercenary Peter Quill — have been grudgingly working together to protect a powerful artifact from falling into the wrong hands. Because they’ve each been pursuing their own agendas instead of working together, they are close to failure. It’s up to Quill (Chris Pratt), to convince them to start working as a team.

“I look around at us, and you know what I see?” he asks them. “Losers.” Noting their incredulous faces, Quill qualifies, “I mean, like, folks who have lost stuff.” He’s right; each of these tentative allies have experienced loss, trauma, and unresolved grief that taught them not to trust others.

‘One Life’ Shows How Small Acts Can Make a Life-Saving Difference

What is any ocean but a multitude of drops?

ONE OF MY favorite literary quotes comes from David Mitchell’s novel Cloud Atlas. When Adam Ewing, a 19th-century notary from California, decides to become an abolitionist and protest the transatlantic slave trade, he imagines his father-in-law declaring that Ewing is condemning himself to a meaningless life that will amount to nothing more than a drop in the ocean. Ewing responds, “Yet what is any ocean but a multitude of drops?”

I thought about that quote while watching One Life, a 2023 film based on the real life o fNicholas Winton, a British stockbroker who, in the year before World War II, rescuedmore than 600 Jewish refugee children in Prague by relocating them to England in what came to be called the Czech Kindertransport. Winton’s determination was indeed amazing, but as the drama shows, his efforts depended on many people who did what they could to help — many drops in an ocean of good.

‘God & Country’ Documents the Christian Nationalist Takeover of Evangelicalism

The new documentary God & Country, inspired by Katherine Stewart’s book The Power Worshippers, fortunately escapes most of the major pitfalls of political documentaries as it addresses the rise of Christian nationalism.

How to Ignore the Screams of Your Neighbors

In ‘The Zone of Interest,’ a Nazi commandant and his family live a seemingly normal life — next door to Auschwitz.

JONATHAN GLAZER’S FILMS aren’t really stories; they’re experiences. His work is moody and image-driven. Plot matters less than concept, which often makes his work feel like it should be viewed in an art museum rather than in a theater. This is certainly true of his latest, The Zone of Interest, a loose adaptation of a novel by Martin Amis.

Glazer’s film follows a Nazi commandant and his family who live next door to Auschwitz. Theirs is a disturbingly wholesome life — a study in what philosopher Hannah Arendt called the “banality of evil,” the bureaucratic just-following-orders mentality that allows evil to proliferate. As such, it’s also a timely film to consider in the context of rising authoritarianism around the world.

Martyrdom or Foolish Fantasy?

John Allen Chau wanted to bring the gospel to North Sentinel Island. The documentary “The Mission” tells the story of his death and raises questions about cross-cultural evangelism.

IN 2018, 26-year-old American missionary John Allen Chau journeyed to the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean. He wanted to minister to the Sentinelese, the Indigenous residents of North Sentinel Island and one of the last population groups on the planet to have avoided modernization by the outside world. Chau, an Oral Roberts University graduate who grew up steeped in conservative evangelical culture, felt called to bring the gospel to unreached people.

The mission did not go as planned. Chau was quickly killed by the Sentinelese, who saw him as a threat. Chau’s death caused a public reevaluation of cross-cultural missions, one explored in the documentary The Mission. The film tells Chau’s story through his diary excerpts, his father Patrick’s account of Chau’s life, and expert interviews.

Directors Amanda McBaine and Jesse Moss don’t cast judgment; instead, they add context and ask questions. Was Chau’s death martyrdom, or the result of a foolish fantasy? Does teaching God’s word to isolated peoples help them, or open them to exploitation, colonization, and eradication?

The Cautionary Tale of the Father of the Atomic Bomb

‘Oppenheimer' confronts us with moral questions about irreversible consequences.

IN CHRISTOPHER NOLAN'S film Oppenheimer, J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) gives a speech to his assembled Manhattan Project team in Los Alamos, N.M., shortly after the U.S. drops an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, in early August of 1945. In a small auditorium in this town built for the sole purpose of developing the bomb, Oppenheimer looks over a crowd of ecstatic scientists and their families, who greet him with cheers. Some of them are waving American flags.

As Oppenheimer starts praising the team and what their great achievement means for the U.S., we’re given a window into his internal torment: The background starts to blur and vibrate. We hear a child’s scream. Oppenheimer sees a woman’s face start to flake away. Looking down, a charred human body clings to his leg. Oppenheimer sweats. He swallows. He continues speaking, but it’s clear he’s dissociated from the speech he’s written.