Feature

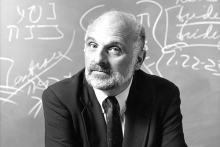

FOUR DAYS AFTER the 2020 presidential election, Sojourners’ then-editor Jim Rice called biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann for his insights on that deeply polarized time, insights that are perhaps more relevant than ever. Their 15-minute phone call on Nov. 7 yielded more of the deep wisdom that Walter had shared with Sojourners since he published his first article with us in 1983. — The Editors

Jim Rice: Where do you think we are and what are we doing as a culture, as a people, and as people of faith?

WALTER BRUEGGEMANN, THE much-beloved biblical scholar and author, died at the age of 92 on June 5. As one speaker at his July 19 memorial service noted, since his death there have been thousands of words written in tribute to Brueggeman in publications (including by Sojourners president Adam Russell Taylor on sojo.net) and on social media. We are add-ing to that word count because of how important Brueggemann has been to us at Sojourners — he has been one of our guiding lights and became a contributing editor in 1989. He was one of several people who helped Sojourners sustain and refine our founding belief that to follow Jesus and live lives shaped by scripture and prayer was intertwined with a commitment to social justice and concrete works of mercy. He indirectly mentored many of us in how to keep the Bible as a living, provocative force shaping our personal integrity, our spiritual growth, and our public witness.

CALLIE WALKER GREW up in central Virginia, where her father farmed cattle on land he’d purchased in the 1960s. Walker, 56, with bright blue eyes and a shock of salt-and-pepper hair, doesn’t know how much land her father originally owned. “It was certainly hundreds of acres,” she said, “and it may have been thousands.”

He spent 30 years paying it off, Walker told me, and succeeded, largely, by selling off a parcel of land here or there to pay the bills. When Walker’s father died in 2014, at 91, he left his three children portions of the remaining acreage; Walker’s inheritance — green, rolling farmland unfurling on either side of a small country road — totaled 134 acres.

Walker attended Princeton Theological Seminary and spent years living communally and working for racial justice. She had known since the 1990s that she wanted to use the property she would one day inherit for some kind of intentional community.

By January 2020, Walker’s intentions for the land clarified: She wanted to give it away.

THIS TALE BEGINS with two Ohio politicians — one famous, the other relatively unknown outside Springfield.

For J.D. Vance, the city was a cudgel, useful in creating a media storm that would attract anti-immigrant supporters to his 2024 race for U.S. vice president. For religion scholar Warren Copeland, Springfield was home, a place to promote the policies that attracted immigrants to Springfield, where he served as mayor from 1990 to 1994 and from 1998 until his retirement in November 2023. Copeland was also a professor of ethics and director of the Hagen Center for Civic and Urban Engagement at Wittenberg University.

JESSICA MOERMAN SPENT years in Malaysian caves and Kenyan lake beds unearthing clues about ancient climate. But when she speaks about the climate change we’re experiencing today she takes a different approach: She begins with scripture.

Moerman, 38, is both a trained climate scientist and an evangelical Christian who espouses a faith of action, not just talk. “I am a climate scientist because of my faith,” she told me.

THIS SPRING, MY family and I were discussing what artistic representations of Jesus’ life have shaped our spiritual lives. For one son-in-law, it was Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, though he noted it is quite violent. For my husband and our adult kids, it was Jesus Christ Superstar. For me, it was seeing “Godspell” in Toronto in 1972 when I was 12. I vividly remember the wide-open energy that kept inviting new disciples into the group of Jesus’ followers, the circus-like performers bursting with enthusiasm, encouraging each other to creatively express what they were discovering together. It was physical, passionate, musical, hilarious. I looked up the musical’s history and discovered that my spirituality was shaped by legends of improv comedy, including Gilda Radner and Martin Short, who went on to be cast members of Saturday Night Live, and Eugene Levy, whose storied career continued this century in Schitt’s Creek.

Perhaps that early spiritual orientation toward freewheeling motion, fun, community inclusion, live performance, and humor is why I appreciate theologian and author Henri Nouwen’s efforts to image our spiritual lives as daring, interdependent trapeze acts.

MY ANCESTORS ARE the Indigenous people of the Samoan Islands in the Pacific Ocean. The island chain is now separated by its colonial legacies: At one point, Germany and New Zealand controlled what is now the Independent State of Samoa, and the United States remains in territorial control of American Samoa.

The consequences of that history forced me to turn inward and clearly hear the lamentations of my ancestors. I think many Indigenous people with similar colonial wounds would agree we just want to heal from our pain. And the only appropriate remedy is justice.

IN 2017, on a year-end retreat, the leader asked what descriptive name we might like to claim for the coming year. I thought a bit and said “elder.” When asked why, I smiled: “Because I could share wisdom without taking responsibility.” It was humorous, but serious too.

In my life I’ve had my share of taking responsibility for organizations and movements in ways that have been rare privileges. I was the legislative director for a U.S. senator working against the Vietnam War. I started an institute committed to strengthening churches’ care for the earth. At the World Council of Churches, I directed its work on church and society, including beginning its focus on climate change. Then the Reformed Church in America selected me to be its general secretary. I played a significant role in beginning and directing Christian Churches Together and served as chair of the board of Sojourners and as president of the Global Christian Forum Foundation. All these efforts involved grace and pain. And, at this point in my journey, all have ended.

Now, I wonder where you are in your long journey of soulwork and justice. Maybe you’re in early days, with new roads and big challenges that are so daunting. I want to share that with you because it is your inward journey with God that will sustain you in your outward journey, joining in what God is doing in the world.

The witness of Christian faith in the public square, if done authentically, has always required spiritual alertness. New crises erupt almost daily, tempting us to endless reactivity. You will need inward spiritual grounding that can make a practical difference in political engagement, social action, and outward witness. Your vision, starting point, and disposition will bear the distinctive features of the Christian witness that scripture and prophetic voices have and continue to note. I invite you to tend, sit, read, pray, and act. Let God ground your life. Over many years and many times of chaos, I’ve identified eight elements that contribute to a spiritually alert, faithfully rooted witness.

SAM’S PARTNER HIT them. Sam knows the partner is at fault, but can’t shake the feeling that getting a “no-fault” divorce would be a lie. “I really don’t know what to say,” admitted a colleague and friend. My friend was a new pastor with a church member in an abusive marriage; we’ll call that church member Sam. My friend walked with Sam as they made the decision to get a lawyer, but they were both overwhelmed with the specifics of the divorce proceedings. “I had no idea there were this many layers to the process,” my friend said. “And frankly, I’m still reeling at the fact that my work as a pastor would include helping someone see the importance of pursuing a divorce, but I just don’t think Sam will survive in this marriage.”

Christian tradition holds marriage to be a public, sacred covenant made by two people before God, intended to be a lifelong commitment. Yet as Christians know as well as anyone — divorce rates among Christians are comparable to the general population — marriages end in divorce for a variety of reasons ranging from poor communication to domestic violence or abuse. Some Christians are against divorce in nearly any circumstance; other Christians are more open to divorce as an acceptable choice, but do not know the different legal options, what these options afford the individuals seeking a divorce, and how those options may or may not align with their faith. And regardless of a church’s views on divorce, I’ve observed that few churches talk openly or well about it.

My journey with this topic began in 2015 with my own divorce. Unlike Sam, I was not a victim of domestic violence. But like Sam, I didn’t want a divorce — and I really didn’t want a no-fault divorce. In the U.S., couples typically choose between an often-lengthy fault-based divorce, where blame is assigned (e.g., abuse, adultery), and no-fault divorce based on irreconcilable differences, which keeps a couple’s opinions about where fault lies separate from the legal process — and is usually quicker. Choosing “no-fault” felt dishonest to what I’d experienced. I couldn’t square it with my faith; it felt too quick, too easy. I wanted to feel the vindication that I thought assigning fault might bring. These feelings were fueled by a lingering sense of self-righteousness rooted in my religious convictions.

The ivory-billed woodpecker has been called “Lord God Bird,” for its massive size; “Grail Bird,” for the fervor with which people seek it; and “Ghost Bird,” for the way it hovers on the murky edge between existence and extinction. But Cornell ornithologist Tim Gallagher, author of The Grail Bird, calls it “Lazarus Bird,” after the story of Jesus resurrecting his friend Lazarus four days after he died.

Growing up in the church, I was never sure what to do with resurrection. My father’s faith didn’t emphasize the idea that Christ died for my salvation, or that Christ’s believers would be raised from the dead, but these beliefs were everywhere—in the hymns we sang in the various United Methodist churches where he served as pastor, in the creed we recited every Sunday: I believe in ... the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting.

From my seat in the pews, the promise of everlasting life rang hollow. I did not expect decomposed bodies of believers would one day be reconstituted, nor did I see this as desirable for myself or the people I loved. But metaphorical interpretations of resurrection also fell short: A body raised symbolically from the dead is still very much dead. In graduate school, I read about Thomas Jefferson’s excision of miracles, including the resurrection, from his Bible with a sense of relief. The stories I couldn’t believe literally or understand figuratively, could be simply cut away. But as I’ve grown older, these stories resist neat excision. To dismiss resurrection entirely feels increasingly fraught: Why did faith matter if it did not transform real bodies, real lives, here on earth?

If you drove down Filbert Street in Center City Philadelphia in February 2025, you might notice a few things. The street is not very wide. There’s a train station. And a large, boarded-up building, surrounded by fencing—it used to be a Greyhound Bus terminal. A sign on a pedestrian walkway says “Fashion District.”

Soon, you’d see an “All Traffic Must Turn Left” sign. And since you are traffic, you turn left — and quickly realize you’re in Chinatown. Make another left to Arch Street, and you’ll find Chinese characters on almost every storefront, even on “The Bank of Princeton.” On nearby Race Street, there’s a historical marker that reads:

Philadelphia Chinatown

Founded in the 1870s by Chinese immigrants, it is the only “Chinatown” in Pennsylvania. This unique neighborhood includes businesses and residences owned by, and serving, Chinese Americans. Here, Asian cultural traditions are preserved and ethnic identity perpetuated.

But remember Filbert Street and that boarded-up bus terminal? In summer 2022, the National Basketball Association’s Philadelphia 76ers announced that they wanted to build an 18,500-seat new arena right there, taking up a third of the Fashion District (a shopping mall formerly known as The Gallery), sitting directly above the train station, connecting to the old Greyhound terminal, and removing Filbert Street from the city grid. At the time, the bus terminal was in use, not fenced off — isn’t it funny how things can sometimes work out just how billionaires want them to?

Residents, especially those from nearby Chinatown, almost immediately raised concerns. Two Pennsylvania-based organizations — the Asian Pacific Islander Political Alliance and Asian Americans United — formed a coalition to oppose the building of the arena; about 50 other organizations soon joined. A 2023 survey by the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation found that 93% of business owners and 94% of residents opposed the arena, citing concerns about gentrification, parking, traffic congestion, the deterioration of Chinatown’s culture, and increasing rent and displacement.

Some faith leaders, eager for the jobs new construction might provide their congregants, supported the arena. Many others, including clergy from Black, mainline, and Catholic churches, joined the coalition to protect Chinatown — even though most of their congregations weren’t located there. They were allies. But they weren’t motivated by immediate existential threats to their community.

And then, there was Rev. Wayne Lee.

A CENTURY AGO, the baseball-player-turned-evangelical-revivalist Billy Sunday preached a gospel supercharged by conspiracy theory and nationalism. He spoke against the backdrop of World War I to masses seized by national security anxiety directed at immigrant communities. Deploying a message made urgent and relevant by its conspiratorial frame, Sunday preached, “They call us the ‘melting pot.’ Then it’s up to us to skim off the slag that won’t melt into Americanism and throw it into hell or somewhere else.”

Hellish rhetoric has a long history in the United States for animating theological paranoia in service of supremacist political power. It’s also been part and parcel of American evangelicalism.

Like many kids growing up in evangelical culture in the 1990s, I was extremely familiar with hell. Popular preaching led with hell before it ever spoke of heaven. It described a place of terror reserved for the unbelieving, who always happened to be from the wrong political party or country. In those days, evangelical churches hosted so-called hell houses to “scare straight” teenagers who strayed from a very narrow moral code. My own church did annual dramas depicting people in hell. I prayed the “Sinner’s Prayer” more times than I could count, hoping I really meant it enough to save me for good. If you were to ask me then: “Do you believe in hell?” I would have said “Of course! I’m a Christian!” Belief in hell went hand in hand with belief in Jesus.

My faith today requires me to dismantle the understanding of hell I received as a child and the cultural use of hell popular today in the rise of Christian nationalism. Hell, in the Trump era, is a rogue theological element, unmoored from the Christian story. When Donald Trump says, “I want to make the country great again. This country is a hellhole,” he casts himself, theologically, in the role of Christ, dispensing judgment on who is good and who is bad.

Trump wields diabolical power to throw people to political hells — and that’s what he’s doing. This isn’t new. Poet Langston Hughes wrote prophetically in 1936, “Fascism is a new name for that kind of terror the Negro has always faced in America.”

In this stream of prophetic thought, we are roused to consider our own responsibility today. We cannot look away from the political hells rising up around us, including indiscriminate ICE raids at churches; repurposing the Guantanamo Bay detention camp to hold migrants; freezing funding for critical family services and health programs in the U.S. and around the world; dispossessing hundreds of thousands of civil servants from their livelihood; and blocking asylum access for those in fear for their lives — all creating indescribable suffering for those who don’t fit a very narrow white supremacist or libertarian agenda.

SINCE ITS PREMIERE in late 2023, Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days — a quiet, contemplative film about a janitor who cleans Tokyo’s public toilets — has been showered with accolades, including a Cannes Film Festival Palm d’Or nomination, an Oscar nomination for Best International Feature, two Japan Academy Film awards for Best Director (Wenders) and Actor (Kōji Yakusho), and even an Ecumenical Jury Prize, an independent award created by international Christian media organizations SIGNIS and Interfilm.

All these honors more or less speak for themselves, except — perhaps — the last one. Perfect Days is, after all, neither a Christian film nor an explicitly religious one. Except for the occasional reference to concepts related to Buddhism, such as meditation, karma, and nirvana, the only time protagonist Hirayama seems to make contact with some sort of higher power is when he listens to Nina Simone’s “Feeling Good” on his way to work each morning.

Fortunately for Wenders, Ecumenical Juries — which attend film festivals across the world — don’t limit themselves to the likes of Jesus Christ Superstar or The Passion of the Christ. At least, not anymore. “Initially, the focus was on films reflecting the Christian worldview,” says S. Brent Plate, a professor of religious studies at Hamilton College in New York, longtime Ecumenical Jury member, and author of Religion and Film: Cinema and the Re-creation of the World. “Over time, we shifted toward a broader interpretation of that focus, looking for films that, even if they don’t directly address religion, promote humanistic, progressive values.”

As a result of this shift, the Ecumenical Jury’s mission has come to raise worthwhile questions for film aficionados and religious scholars alike: Can movies function as a mode of religious instruction, bringing us closer to the divine the way a sermon might? Can they teach us how to be better people, inspiring us to lead more fulfilling lives by untangling the mysteries of the human condition? And, most important perhaps, can they nourish our spirit, impart morality, and help us overcome moments of personal crises in an age where the historical provider of such services in the West — the church — is losing its longstanding influence?

I HAD A friend. He died last summer. Actually, to say “He died,” is too passive. He was killed. He was killed as I held him, as those who loved him and those he had hurt watched. On June 26, 2024, the state of Texas executed Ramiro Gonzales for the rape and murder of Bridget Townsend. In 2001, Ramiro was 18 years old, suicidal, violent, and struggling against the chains of addiction; but 23 years later the state took the life of a 41-year-old man who was sober, faithful, and deeply considerate of everybody who surrounded him. He was loved. I miss him terribly.

Ramiro and I first connected in 2014 as pen pals. What started as an exchange of letters blossomed into a friendship spanning more than a decade. There are some who only knew Ramiro for the vicious violence he perpetrated. I’m sympathetic to their anger, but this is not the Ramiro I came to know. As our friendship deepened, Ramiro cherished my children, sending them birthday cards and artwork. We shared in both the sacred and mundane of our daily lives. We also discussed his crimes, his grief, and his profound shame.

After entering the order of ministry in the United Church of Canada, I became Ramiro’s spiritual adviser. This designation allowed me to be with him in the execution chamber, my hand on his chest, singing and praying over him as Texas used a lethal injection of pentobarbital to kill him. It was one of the most haunting and devastating experiences of my life. Not a day goes by when I don’t think about Ramiro, about Townsend, or about everything that went wrong that brought us to that deadly day.

Just a few years ago, the thought of me — a Toronto pastor — sitting inside a Texas death chamber would have seemed unimaginable. Yet, there I was, due to a significant shift in Texas’ execution protocol. The state had moved from allowing only its own appointed chaplains to accompany the condemned in the moment of their execution to granting inmates the right to the spiritual adviser of their choice, a result of years of legal battles over questions related to religious freedom and equity. My journey to that chamber was also defined by the moral dilemma of opposing capital punishment, while simultaneously taking on a vital role within the execution process of someone I cared for deeply.

“WE ARE FULL of fear, but we are not helpless,” said Giselle, a 40-year-old living in a mixed-status immigrant family in Chicago. “We have the power of God, the power of the church, and the power of the Holy Spirit on our side,” she said. (Sojourners is withholding Giselle’s last name due to her sensitive immigration status.)

Giselle is the mother of two children who are U.S. citizens. She is long settled in Chicago, having arrived two decades ago from Michoacán, Mexico. She lives in a three-bedroom apartment in Chicago’s Little Village — known as the “Mexico of the Midwest” or “La Villita” by locals — and works as a bookkeeper and worships at a local Pentecostal church where, she told Sojourners, there are other immigrants without permanent legal status singing next to her on Sundays. She volunteers and donates to local charities and generally tries to be a good neighbor — offering her time, talent, and treasure to others in her little corner of Chicago. Giselle said she has built her life in the U.S. and that her adolescent children know nothing else. “We are proud to be Mexican American, to live life here and be part of this community,” she said.

Like thousands of others across the U.S., Giselle and her family do not know how the Trump administration’s stated mass deportation policies will play out. But as policies are put in place and enforcement efforts ramp up, questions keep running through Giselle’s mind: How will I protect my family? What will happen to my immigration status? How will I be able to seek safety in the U.S.? “These are just some of the questions that handicap my ability to live,” she said.

As the Trump administration continues to implement its mass deportation plans, a swirling vortex of pain, fear, and uncertainty dominates the conversation among immigrants and faith communities across the nation. People of faith are responding with hope, resilience, and a steady resolve to be the best neighbors they can be to immigrants in need.

SEEING THE RISE of right-wing populism globally, several months ago I began to lead scenario-planning and writing about what might happen if Donald Trump won. I played out strategies for how folks might meaningfully respond. Yet when he won, I still found myself deep in shock and sadness. In the days after, I reached out to my community to try to assess and get my feet back underneath me.

Being grounded is difficult when the future is unknown and filled with anxiety. Trump has signaled the kind of president he will be: vengeful, uncontrolled, and unburdened by past norms and current laws. If you’re like me, you’re already tired. The prospect of more drama is daunting.

As a nonviolence trainer working with social movements across the globe, I am blessed to have worked with colleagues living under autocratic regimes to develop resilient activist groups.

My colleagues keep reminding me that good psychology is good social change. For us to be of any use in a Trump world, we must pay attention to our inner states, so we don’t perpetuate the autocrat’s goals of fear, isolation, exhaustion, and constant disorientation. As someone raised by a liberation theologian, I’m reminded of how we lean hard on community and faith in tough times.

In that spirit, I offer some ways to ground ourselves for the times ahead.

AT A KEY JUNCTURE in Luke’s narrative of Jesus’ public ministry, the Nazarene spins the short, foreboding cautionary tale of Lazarus and the rich man (16:19-31). It is set in the afterlife, where a rich man who is a model of entitlement and denial encounters Abraham, the primal progenitor of his people. They have a tense and terse exchange, albeit at a distance.

Abraham tries to explain to him two truths about the economic life and world the rich man has just left. First, his wealth was predicated upon a fatal sociological, moral, and theological condition the patriarch calls a chasma mega (“huge gulf”). It separated and insulated him from people who were impoverished and dehumanized by the system that created and sustained his privilege, people whose pain can only be grasped from their side of that social chasm. Second, to find the will and way to eradicate this cruel gulf, the rich man must reread his sacred scriptures.

This tale lies at the center of a series of seven decidedly unflattering portraits of rich men in Luke’s gospel. This series forms the backbone of the middle section of the longest gospel. It is framed before and after by two indictments: of a rich farmer’s selfishness (12:16-21) and of wealthy lawyers’ exploitation of poor widows (20:45-47; 21:1-4). This middle parable functions as Luke’s “narrative fulcrum” and articulates his keystone theme.

It also speaks plainly to our historical moment. We live in an era in which persistent economic disparity threatens social coherence, democratic prospects, and ecological viability. But Luke also assures us that the biblical vision of Sabbath economics represents ancient medicine that can animate the political imagination necessary to heal this otherwise terminal disease.

Jesus’ earlier beatitudes (6:20-26) and disciples’ prayer (11:1-4) proclaim good news to the poor. His realistic parable of the “Defecting Manager” (16:1-12), on the other hand, addresses those caught between the conflicting demands of Sabbath economics and plutocracy or rule by the wealthy (this includes most of us in North America). The “Defecting Manager” parable concludes with an ultimatum: “You cannot serve God and mammon” (16:13). Sabbath economics is rooted in God’s instructions to dismantle, on a regular basis, the fundamental patterns and structures of stratified wealth and power, so that there is enough for everyone.

It is then, to show us the consequences of failing to deconstruct systems of violent social and economic inequality, that Jesus offers the parable of Lazarus and the rich man, a surreal image of a dark mirror. Here, the brutality of disparity is purgatory: for the poor in their daily life; for the souls of the rich here and hereafter; and for all our prospects of peaceable equilibrium in society. Here too, the flames of Hades become a contemporary allegory for our warming planet under climate crisis.

Since mammon ultimately ravages both haves and have-nots (if in different ways), our parable challenges all of us infected with affluenza to view the world upside down — because the truth of social divides can only be seen from their other side.

A LITTLE OVER a year ago, members of Ann Arbor’s Zion Lutheran Church in Michigan stood on an L-shaped plot bordering their church garden. Those 800 square feet of ordinary lawn were on the cusp of transformation, about to become the source of Zion’s own Communion bread.

While Christians traditionally think of Communion as transforming partakers during the church service, project leader Betsy King-McDonald wanted to explore the life-giving properties of the Eucharist at an earlier stage — starting in the soil.

“How can we foster life in all the choices we make to the table?” she asked. This question led King-McDonald, a doctoral student at Western Theological Seminary, to partner with Zion Lutheran in growing heirloom wheat for their Communion bread.

In the slanting October light, members rototilled the church lawn. Youth lugged wheelbarrows of wood chips from the parking lot. Then Joet Reoma, a local master gardener and board member of Project Grow, a local nonprofit that facilitates community gardens, directed participants in a complex ritual that resembled making a dirt lasagna. The “lasagna” was not for humans, but for the microbial life in the recently turned soil.

In a trademark black cap with tag still attached, his name scrawled on the tag in bold black marker, Reoma called out basic permaculture steps: First, spread fresh wood chips, high in nitrogen but slow to decompose. Next, add a layer of vermicompost — worms with their eggs and castings, ready to break down the organic matter. Sprinkle cornmeal on top, energizing the worms and kick-starting mycelial growth in the wood chips. Finally, two more layers; one of decomposed wood chips and one of compost. Now, the soil community was ready to receive the wheat seeds.

This elaborate process of feeding the soil that would nurture the church’s Communion wheat expressed a deep eucharistic truth — the process and the produce hold the power of life.

Rarely do churches interrogate how liturgical elements support life all along the way — from soil to markets to table. As King-McDonald found, tending to the process clears a path for deeper place-based Christian discipleship.

After poking neat rows of holes in the living soil, Zion Lutheran’s team dropped wheat kernels into the darkness, covered them, and spread a layer of straw over it all.

JERUSALEM'S OLD CITY has often been a focal point of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but within its walls lies a lesser-known story of occupation and resilience. The Armenian Quarter, a Christian enclave that has endured for centuries, now finds itself under threat.

In the context of occupied East Jerusalem, where Palestinians continually face displacement and erasure of their cultural and physical presence, the Armenian community’s struggle reflects a larger pattern. Though they make up a small portion of the city’s population, Armenians have called Jerusalem home for more than 1,700 years, surviving waves of conflict and colonial powers.

As a critical component of a shared Jerusalem between Jews, Christians, and Muslims, the Armenian Quarter has been a haven for this Christian community since a group of Armenian monks and priests established St. James monastery there in 420 C.E.

The enclave is now fighting to preserve its heritage amid mounting pressures. In April 2023, the community was shaken by plans from an Israeli-Australian developer, Xana Capital, to construct a luxury hotel on land purportedly owned by the Armenian Patriarchate. This development mirrors the land confiscation and settlement expansion that Palestinians know all too well.

Like the rest of the Christian population in the Old City, including the Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Ethiopian Orthodox, the Armenian community is navigating increased challenges, from economic strain to political pressures and demands to shift the historic status quo. These communities, increasingly pressured by Israeli authorities and settlers, face a myriad of problems, including property disputes, confiscation of church lands, new and prejudicial tax demands, and occasional acts of vandalism against religious sites. All Christian groups are grappling to maintain their historical presence in the face of growing threats in this contested city.

I WAS VISITING my sister and niece in Maine with my middle daughter when we learned that Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon died. Our aunt in Oakland sent the obituary to our mom in Ohio, then Mom texted us: “Thought immediately of you both and all that she and her music meant to us. Long, lovely memories.”

Even in the news of her passing, Reagon, the founder of the celebrated music ensemble Sweet Honey in the Rock, was connecting women across generations, geography, religious, and racial categories. The music of Sweet Honey helped my mom, a white Quaker woman and Methodist pastor from rural Ohio, find her voice. It also shaped my sister and me as biracial Black women growing up in Washington, D.C. in the ’80s and ’90s. I took a course from Dr. Reagon during my senior year in high school. I never saw her again. Waves of grief and gratitude washed over me.

The day we got the news, we woke in a tent after camping near where the sun rises first over North America. As we drove past towering pine trees, taking in the news of one more passing — each death stirs up the sadness of all the other losses and more to come — my sister and I played our favorite Sweet Honey songs. We sang along to Reagon’s “I Remember, I Believe” from the 1995 Sacred Ground album: “My God calls to me in the morning dew / The power of the universe knows my name / Gave me a song to sing and sent me on my way / I raise my voice for justice, I believe.”