Julie has been a member of the Sojourners magazine editorial staff since 1990. For the last several years she has edited the award-winning Culture Watch section of the magazine. In her time at Sojourners she has written about a wide variety of political and cultural topics, from the abortion debate to the working class blues. She has coordinated in-depth coverage of Flannery O’Connor, campaign finance reform, Howard Thurman, the labor movement, and much more.

She studied English literature at Ohio State University and has an M.T.S. (focused on language and narrative theology) from Boston University and an M.F.A. in creative nonfiction from George Mason University.

Julie grew up on a farm in the northwest corner of Ohio. She has been fascinated by the power of religious expression in and through culture since she can remember. Obsessively listening to her older sister’s copy of the Jesus Christ Superstar cast recording when she was 10 was an especially crystallizing experience. In addition, Julie’s mother often argued about doctrine and the Bible and took her at least weekly to the public library, both of which were useful background for Julie’s current work.

She lives in the Columbia Heights neighborhood of Washington, D.C. and is a member of St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church (where she had an unlikely four-year reign as rummage sale czarina). Her personal interests overlap nicely with her professional ones: Music, books, reading entertainment, culture, and religion writing, art, architecture, TV, films, and knowing more celebrity gossip than is probably wise or healthy. To make up for all that screen time, she tries to grow things, hike occasionally, and wonder often at the night sky.

Some Sojourners articles by Julie Polter:

Replacing Songs with Silence

Censorship, banning, blacklists: What’s lost when governments stifle musical expression?

Extreme Community

A glimpse of grace and abundance from - of all things - reality TV.

The Cold Reaches of Heaven

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Bill Phillips talks about his faith.

Just Stop It

Daring to believe in a life without logos. An interview with journalist Naomi Klein.

Women and Children First

Developing a common agenda to make abortion rare.

Obliged to See God (on Flannery O’Connor)

Posts By This Author

Beholding God’s Glory During Inglorious Times

Human concepts of grandeur and power can’t compare.

IN A 2024 interview, priest, preacher, and author Fleming Rutledge noted that “Epiphany directs us to behold—that’s a revelatory biblical word, behold—the glory of God in Christ as he moves through his time on earth with us through his death into his ultimate victory.”

I think of myself as a fairly orthodox Christian, embracing Jesus as fully God and fully human; I am a believer in angels and miracles and the resurrection. But I don’t know that I grasp all aspects of beholding the glory of God. Don’t get me wrong—an infinite deity is a wonder to me, and I believe in God still and always, despite all that can feel God-forsaken in this life, from massacres to preening, vengeful leaders.

Billionaires Are a National Disaster

Chuck Collins on how income inequality undermines everyone’s quality of life—even the most wealthy.

CHUCK COLLINS WAS “born on third base.” As a scion of the Oscar Mayer meat processor fortune, Collins was firmly in America’s top 1%. However, at age 16, he began reading The Catholic Worker newspaper, co-founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin. Within two years he was living with the Mustard Seed Catholic Worker community in Worcester, Mass., serving soup to homeless men. Day’s philosophy of “nonviolent economics” exposed Collins to the violence caused by economic systems. Day believed that there is a “social mortgage on capital” and that society has a claim on private wealth, since it comes from the commons. At age 26, Collins made what he called “the first real adult decision of my life.” He gave away the half-a-million-dollar trust fund his parents had set up for him to local and national groups working for social change.

For 40 years, Collins has organized for a more moral economy. “The prophets, then and now,” he’s written, “call us to a discipleship of equality, working for a society that leaves no one behind, and where all can thrive.” Author of a dozen books, Collins’ newest is Burned by Billionaires: How Concentrated Wealth and Power Are Ruining Our Lives and Planet. He is a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies where he directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good and co-edits inequality.org. He lives in Vermont. Sojourners editor Julie Polter interviewed Collins in September via Zoom. —The Editors

He Sent Troops, but We Were Ready

In Washington, D.C., solidarity, go-go concerts, defiant joy, and pointed humor offer a path for all cities facing federal occupation.

Those of us who live in the District of Columbia grow accustomed to watching major events unfold in our city. But the hyped-up “crime emergency” President Trump declared in Washington, D.C. in August was different.

An alphabet soup of federal law enforcement officers—DEA, FBI, Park Police, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, ICE—joined National Guard troops and our police force to set up checkpoints, patrol neighborhoods, and arrest people for some felonies, yes, but according to an NPR report, mainly misdemeanors, traffic offenses, or charges that were later dropped. Friends and neighbors shared chilling footage of aggressive immigration enforcement; one friend described the helpless feeling after watching ICE surround a car, break a window, and snatch a neighbor.

We are not the first U.S. city this year to face armed soldiers (we see you, L.A.) or the last. But D.C. has fewer official means to push back: The District only gained “home rule” in 1973 and Congress can—and does—override laws approved by our council or voters. The president can also intercede in our affairs.

Walter Brueggemann Was No Dour Prophet

WALTER BRUEGGEMANN, THE much-beloved biblical scholar and author, died at the age of 92 on June 5. As one speaker at his July 19 memorial service noted, since his death there have been thousands of words written in tribute to Brueggeman in publications (including by Sojourners president Adam Russell Taylor on sojo.net) and on social media. We are add-ing to that word count because of how important Brueggemann has been to us at Sojourners — he has been one of our guiding lights and became a contributing editor in 1989. He was one of several people who helped Sojourners sustain and refine our founding belief that to follow Jesus and live lives shaped by scripture and prayer was intertwined with a commitment to social justice and concrete works of mercy. He indirectly mentored many of us in how to keep the Bible as a living, provocative force shaping our personal integrity, our spiritual growth, and our public witness.

Why Does Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Love the Phrase “Common Sense”?

The adage “follow the money” may apply.

HEALTH AND HUMAN Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. seems fond of the phrase “common sense.” In April, he insisted that autism is now an “epidemic” (a view not shared by most scientists who study autism), asserting that “it just takes a little common sense” to agree with him. At a White House event in May for a new report on children’s health — one subsequently criticized for multiple significant errors, including misrepresentation of study results — Kennedy said, “We’ve relied too much on conflicted research, ignored common sense, or what some would call ‘mother’s intuition.’” In June, he fired the 17 members of the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices, replacing them with eight allies he described as “committed to evidence-based medicine, gold-standard science, and common sense.”

Common sense is defined by Merriam-Webster as “sound and prudent judgment based on a simple perception of the situation or facts.” Often what in good faith seems to be “common sense” isn’t the right solution. Experience or new information can overturn accepted wisdom. Careful policymakers might advocate a solution to a societal problem that in practice has unintended negative outcomes. But Kennedy, a former environmental lawyer, is also a conspiracy theorist and anti-vaccine activist who picks and chooses among studies, scientists, and influencers. Perhaps he is a true believer in his social engineering schemes, but his consistent undermining and avoidance of rigorous expert review feels too convenient.

Grandpappy Was on the Wrong Side of History

What does that require of me today?

I GREW UP in Northwest Ohio, in the house where my dad was born. My mother was from Eastern North Carolina. My dad’s paternal great-grandparents immigrated to Ohio from Germany in the 1870s. My mom didn’t know much about her people, except that they’d always been rural and not well off.

A relative once sardonically expressed thanks that our paternal ancestors left Germany long before they could become Nazis and that our Southern relatives were all probably too poor to have enslaved people. The implication was that the only surefire ways to avoid complicity in great evil are chance and circumstance. History has heroes, resisters, and those who spur and lead wickedness; but many people just get caught up in sheer survival or go along to get along. Sometimes moral choices are made in imperceptible increments, and personal agency can feel elusive.

I’ve been thinking about this because of the push by the Trump administration, Heritage Foundation, and others to rewrite, rearrange, and obscure history in the name of countering the “evil” of diversity, equity, and inclusion. They are trying to scrub the record to make straight white males the heroes of an imaginary world where even their most brutal, depraved actions were justifiable means to “greatness.”

Research Doesn’t Matter ... Until Someone You Love Gets Cancer

Keep paying attention to the downstream effects of the Trump administration’s deadly budget cuts.

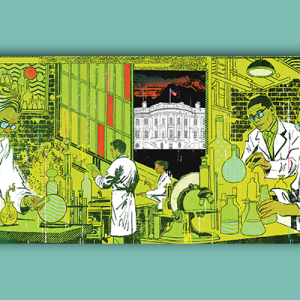

When I was just shy of 18, I watched my mother die of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. CLL killed her less than two years after diagnosis. She was 51. Fast forward a few decades: Over the past 30 years, researchers have discovered biomarkers for a variety of cancers, including CLL, which can aid in diagnosis, assessing prognosis, and developing new, more targeted treatments. We know all this because of uncountable experiments over many years in hundreds of labs, any one of which might be studying some single molecular-level phenomenon that to a lay person would seem insignificant. But through expertise, collaboration, and time, the work of a given group of researchers joins with that of others to, for example, connect the dots between this gene mutation and that protein and this prognosis and that new treatment. The microscopic swells to become a few more years with someone you love.

In the U.S., these advancements have been fueled in large part by the National Institutes of Health, through grants that annually support more than 300,000 biomedical researchers at more than 2,500 different institutions. Through the NIH, the National Science Foundation, and other government entities, the U.S. has funded more scientific research through our tax dollars than any other country. NIH funding supports research on a range of illnesses, substance abuse, health disparities, and drug development. It also contributes to local economies. In 2023, every dollar given in grants generated more than $2 of economic activity. It has been a powerful model of building good things through investing in individuals, institutions, collaboration, and a shared future.

Massive budget cuts, firings, and grant freezes threaten the NIH and future scientific progress. It’s just one piece of the chaotic rush by President Donald Trump and billionaire sidekick Elon Musk to dismantle and discredit government agencies and institutions under the guise of cutting costs and uprooting fraud, all while stoking unfettered bigotry.

Love Is Still a Viable Choice

Being brave has never really been my thing. But I’m trying to practice, one day at a time.

WHEN RAGE OR disappointment, petty or vast, grips me, I sometimes lower my blood pressure with Lyle Lovett’s song “God Will,” in which the narrator asks his unfaithful partner who will trust, love, and forgive them for a litany of sins. The narrator answers his own questions in the chorus:

God does, but I don’t

God will, but I won’t

I use these words in the moments when I’m unable to release anger or to feel love toward those who have caused harm — I may be steaming, but I’ll accept for now that God loves and will forgive the people who I won’t (for now). There, in that space between who I am and who I believe God to be, my fury and pain can bide their time.

I have muttered “God will, but I won’t” a lot since Election Day, about political leaders and operatives who infuriate me and those who voted them into power.

We Elected an Authoritarian. What Role Did Religion Play?

Decades of investment in a larger anti-democratic movement would not have dissolved even if they had been defeated at the ballot box in this election cycle, says journalist Katherine Stewart.

IN NOVEMBER, THE United States joined Argentina (Javier Milei), India (Narendra Modi), and Hungary (Viktor Orbán), among other countries, when it elected an authoritarian as its chief executive. In the case of Donald J. Trump, examples of these far-right tendencies include plans for mass deportations, promises to replace nonpartisan government employees with loyalists, and threats to put political critics on trial.

How did we get here? And what do we need to know to mitigate harm, save what and who we can, and work toward a more free and equitable future? Some of us may feel weary and defeated, but journalist Katherine Stewart, who has investigated the authoritarian movement for more than 15 years, encourages curiosity: “We can’t address our problems unless we know what they are.” Those problems include “decades of investment in a larger anti-democratic movement that would not have dissolved even if they had been defeated at the ballot box in this election cycle.”

In her forthcoming book, Money, Lies, and God: Inside the Movement to Destroy American Democracy, Stewart explores a network of strange bedfellows who drive a broad authoritarian movement both in the United States and abroad. The players in this network have different motivations: Ultra-rich funders aim to destroy the regulatory state to gain even more wealth, funneling resources to groups that further their aims. “New Right” academics and proto-academics pursue the ascendance of their pet ideologies. Veteran political operatives find new partners in the hunt for power.

Though many of the funders and power players within this movement are not Christian or even religious, Christian symbols, pastors, and churches have played a key role. Christian leaders — white evangelicals, but also conservative Catholics, Pentecostals, and others — and the warped theologies they peddle have helped convince voters that we are in a state of emergency. As evidence, these Christians baptize anxieties about sexuality and gender, the economy, and shifting demographics as evidence that America has lost its way and needs to be saved by a strongman.

Stewart’s other books include The Good News Club: The Christian Right’s Stealth Assault on America’s Children (2012) and The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism (2020), which was the basis for the 2024 documentary God & Country. Stewart spoke with Sojourners editor Julie Polter before and after the November 2024 U.S. election. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What This Election Season Has Obscured About the Toll of War

I’ve been in grim awe of the many ways military service is used and twisted in political campaigns.

ON NOV. 11, the world observes Armistice Day, Remembrance Day, or what we in the U.S. call Veterans Day. In the U.S. it is meant to honor anyone who served in the armed forces.

If you know Sojourners — which has a long history of anti-war activism, sharing the gospel call to nonviolence, and naming and critiquing the destruction wrought by the U.S. military-industrial complex — you may wonder where I’m going with this.

This election year I’ve been in grim awe of the many ways military service is used and twisted in political campaigns. Historically, a candidate’s military service is treated as a badge of strength and patriotism. It’s why real and false accusations of “stolen valor” (mispresenting one’s service record) are a common tactic in political campaigns, as opponents try to defuse a veteran’s “advantage.”

The Calculus of Responsibility and Complicity

How can I marvel at the miracle of humanity while watching children die?

One week this spring, my Instagram feed served up: A detail from a ground-breaking cellular-level map of a cubic millimeter of the human brain, showing a single neuron connected with more than 5,600 nerve fibers. The ebullient smile of a 9-month-old relative. And the lifeless, emaciated body of a child in Gaza. Awe. Joy. Horror. I keep thinking of them all.

We hold babies we love, stare into sparkling eyes, and can almost see the wonder of their becoming, the miracle of a brain building myriad connections in a split second. We study soft faces that carry the genetic whispers of ancestors known and unknown. We become acquainted with tiny beings who are also full, unique people, revealing themselves more every day. Christians believe humans are made in the image of God. But how often do we meditate on that radical miracle? Recall holding someone in your arms who is unable to care for themselves and is utterly vulnerable, and yet blooming with infinite potential. Imagine God holding us and seeing the same thing.

In our brief moments of connecting with God, are we able to glimpse what it’s like to live as if imago dei were true? To understand for even a fleeting moment that “in the image of” is, in divine grammar, a verb, not just a noun, the signal flow between created and Creator? We are not just autonomous identities to God, who invites us to hold all human beings in that nexus of tenderness, love, and mystery that a beloved child engenders in us.

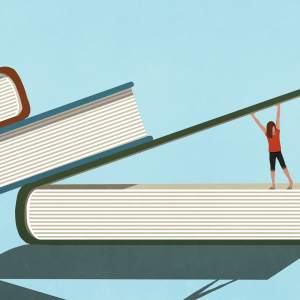

Book Bans Are Almost Never Just About Books

From 2022 to 2023, there was a 92% increase in books targeted for censorship at public libraries.

I WAS WHAT library advocate Mychal Threets calls a “library kid.” My mother, a high-school dropout who loved to read, took me almost every Saturday. One of my earliest memories is playing in the stacks while she picked out romance novels and murder mysteries. This 1903 Carnegie library, one of almost 1,700 U.S. libraries funded by industrialist Andrew Carnegie between 1886 and 1919, seemed elegant and grand to a Midwestern country kid. When I was a little older, the children’s annex became my spot — modern and sunlit, with kid-sized bookshelves and chairs.

I could check out as many books as I wanted, on any topic, with my very own library card. It was like a candy store without threat of cavities.

Public school and the library were my first experience with the commons — cultural or civic resources accessible to all. Libraries offer books, but also other media and things like board games for borrowing; meeting space; and access to computers, quiet, and air conditioning. They often house local history collections.

What’s not to love about spaces and books open to all? But attempts to ban books have also been part of the fabric of library life. A parent or a local group might challenge a book they deem risqué, biased, or ideologically dangerous. Historically these book challenges have come from both the Left and the Right.

Why Christians Should Care About Press Freedom

The first month of the Israel-Hamas war was the deadliest for journalists in at least 30 years.

Editor's note: As of Jan. 10, 2024, the Committee to Protect Journalists has documented at least 79 journalists and media workers killed in Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank since Oct. 7. This article will appear in the forthcoming February/March issue of Sojourners.

IN OCTOBER, NEARLY a week after the brutal Oct. 7 attack by Hamas militants on Israeli citizens, an Israeli military tank crew at the Israel-Lebanon border fired at a group clearly identified as press. Reuters’ journalist Issam Abdallah was killed, and six others were injured. Israel denied targeting the journalists.

While the Israeli government continues to say that the incident is under review, in December, human rights groups Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, along with wire services Reuters and Agence France-Presse, released the results of their own investigations into the Oct. 13 missile strike.

The journalists were reporting on skirmishes between Israeli forces and Hezbollah militants. They were wearing blue helmets and flak jackets, most marked “Press.” One of their vehicles had “TV” on the hood. They had been on a hilltop on the Lebanon side of the border for around an hour before the attack. An Israeli helicopter hovered above them for 40 minutes of that time. Their identity as members of the press — civilian journalists — should have been clear.

The Cutest of the Four Rodents of the Apocalypse Invaded My Attic

What happened next was nuts.

I RECENTLY SUFFERED a home invasion by one of the Four Rodents of the Apocalypse, which are mice, rats, squirrels, and something called “roof rats” (rats tired of the climate-change-induced uptick in flooding of sewer-front properties). I was blessed with the deceptively cutest of these four: Squirrels. In. My. Ceiling.

(Reader, I want to be clear that “squirrels in my ceiling” is not a reference to my scattered thoughts but to literal bushy-tailed rodents doing tumbling runs in the crawl space above a bedroom.)

Squirrels strike a rare balance: They are both adorable and terrifying (like some toddlers I know). One day they’re hanging upside down outside the window to say hello or sitting and nibbling on a nut held just so in their wittle paws, so winsome! The next, a squirrel appears out of nowhere as I enjoy a sunny day on my front stoop, its eyes locked on mine. It skitters forward, then freezes. Forward and freeze, forward and freeze, like a glitchy squirrel robot. It is undeterred by “Shoo!” or “What do you want from meeeee?” Staring blankly, it just keeps coming — for the peanuts it imagines are in my pockets? For my soul? Or are there now flesh-eating squirrels? I run inside and lock the door.

What Song Should We Sing for the Dead?

We are a country where slaughtered kids are sent to their graves in candy-colored caskets while politicians and weapons manufacturers rake in power and profit.

NUMBNESS IS GOOD for dental work and as a temporary coping skill in surviving direct traumas. But most of us are not survivors of tornados or wildfires, haven’t lost our loved one to a young man with an assault rifle, nor worked triple ICU shifts at the peak of the pandemic. Yet many of us, myself included, hunker down deeper into whatever task is at hand when another breaking news bulletin about a mass shooting pops up on our phone. We barely glance at the latest tally of U.S. COVID-19 deaths or reports on war and natural disaster.

A few things recently have cracked open my numbness and made me wonder if we owe it to the dead and the grieving to let our hearts break.

I first saw the photo of a child-sized casket decorated with princess pink and a TikTok logo in a story shared on Instagram. Trey Ganem, a man who has a business creating custom caskets, had donated his work to the grieving families in Uvalde, Texas, where 19 children and two teachers were killed in their school by an 18-year-old with an assault rifle. Ganem sat with parents and asked about their children. Then he and his team made designs reflecting the delights and obsessions of typical childhoods: TikTok. Spider-Man. Softball. Whales for the girl who dreamed of becoming a marine biologist. The colors were bright and glossy; the caskets’ handles and trims were lovingly painted to match.

In the past I might have pondered the prevalence of commercialism in both American childhood and the funeral industry, or the cultural history of how we grieve. But this was only days after the Uvalde shooting, and the juxtaposition of cheerful designs on obscenely small caskets brought a rush of feeling: I wept at a stranger’s heartfelt attempt to bring solace to the inconsolable. I was deeply agitated that we are a country where slaughtered kids are sent to their graves in candy-colored caskets while politicians and weapons manufacturers rake in power and profit.

‘If We Don't Change, the World Will Soon Be Over'

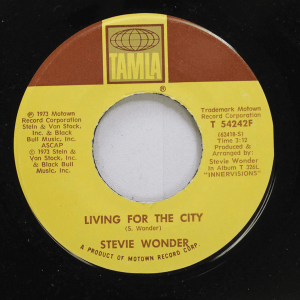

Stevie Wonder's "Living for the City" is a masterpiece of moral formation, motivating us "to make a better tomorrow."

THE OPENING IS spare, just electric piano over a gently throbbing synth bass line, and then the vocal: “A boy is born in hard time Mississippi / surrounded by four walls that ain’t so pretty.” The radio cut of Stevie Wonder’s 1973 hit song “Living for the City” is a four-verse sketch of a loving Black family who work hard, live right, and yet can’t get ahead under the racist economic and social strictures of their Southern town. The instrumentation builds quickly—drums, synthesizer, hand claps, backup vocals—all performed by Wonder. It fades out on a choir of Wonders, singing variations of the chorus: “Living just enough, just enough for the city.”

The album version, more than 7 minutes long, segues from that repeated chorus into a spoken interlude. The boy of the first verse is now a young man arriving in New York City. He is quickly arrested for unwittingly taking a handoff of something illegal and incarcerated for 10 years. The melody and vocals return, heavier, rougher, with Wonder singing from “inside my voice of sorrow” to describe a now broken man who wanders the city, homeless.

“Living for the City” is from the album Innervisions, the third of an astonishing run of five albums Wonder released between 1972 and 1976. During this period, Wonder, a self-taught multi-instrumentalist who made his recording debut in 1962 as a 12-year-old, was stretching lyrically, innovating musically, and embracing a deeper social consciousness.

Two Devotionals That Inspire Us to Connect to Creator and Creation

'Time to Grow' by Kara Eidson and 'Becoming Rooted' by Randy Woodley remind us that our bodies and souls are intertwined.

DEVOTIONALS AND OTHER daily readings can set and solidify intentions in a new year, enrich liturgical seasons, or serve as a spiritual touchpoint during hectic days. Two new books set out to root such soul work in a deepened relationship with creation. Christian theologian and scholar Randy Woodley is a Cherokee descendant recognized by the Keetoowah Band. He and his wife, Edith, an Eastern Shoshone tribal member, develop and teach sustainable Earth care based on traditional Indigenous practices in North America. Along with skill-sharing, they “hope to help others love the land on which they live.” In Becoming Rooted: One Hundred Days of Reconnecting with Sacred Earth, Woodley notes that even those of us who are not Indigenous have ancestors who likely lived somewhere for generations in community with the soil, water, plants, and animals around them.

Woodley has written 100 short daily meditations, each with a suggestion for reflection or action, to encourage all of us to “recover or discover” these values of living in harmony and balance with creation. He draws on Indigenous thought and practice, past pastoral experience, lessons from the natural world, and insightful critiques of the so-called American Dream. Through beautiful descriptions, such as how American violet seeds are dispersed by slugs and ants—“Then in the spring, another field adorns itself with food, medicine, and beauty”—and more somber reflections on the physical and spiritual toll of destructive systems, Woodley models a humble, prophetic invitation: “To accept our place as simple human beings—beings who share a world with every seen and unseen creature in this vast community of creation—is to embrace our deepest spirituality.”

Confronting the Privatized Blessing of Domestic Life

Sexism undervalues work performed by women and shapes policy and economic forces.

I WAS A weird kid who faithfully read the syndicated “Hints from Heloise” newspaper column and the household tips in my mom’s many women’s magazines. I loved how a mundane problem in everyday life could be cheerfully solved with vinegar and “elbow grease” or the strategic deployment of a couple of rubber bands.

This was before Martha Stewart famously built an empire providing perfection-oriented household advice, such as mopping tips that note “sparkling floors begin with the correct tools.” In contrast, the advice in my childhood was humbler, with a how-to/can-do spirit that acknowledged that making a home clean and safe, and keeping a family fed, clothed, and nurtured on a budget is difficult and time-consuming.

When I was young, this was still sometimes called “women’s work.” Religious conservatives and organizations such as Focus on the Family added a faith twist—a woman’s role in the home was sacred duty (based on Jesus’ lost parable of the submissive helpmate?). The term “women’s work” is less common now, but studies show that in households where both a male and female partner are employed outside the home full time, the woman is still more likely to do more of the domestic work.

The Art of Redeeming Our Battered Era

Artist Makoto Fujimura on loving what is broken and the holy work of repair.

Artist Makoto Fujimura uses materials and techniques from nihonga, a Japanese style of painting. The pigments are pulverized minerals and precious metals applied in multiple layers, in what he describes as “a slow process that fights against efficiency.” Prayer and contemplation are woven into the work. The tiny mineral particles refract light, often creating subtle prismatic effects. It is a style of art made for the type of long, unforced gaze that slowly reveals evermore depth. Deceptively simple and quietly extravagant.

Fujimura’s thoughts on art, theology, and culture are, like his paintings, many-layered and refractive, celebrating God as love, beauty, and mercy while also contending with pain and desolation. He is a mystic as well as a painter, and in his latest book, Art and Faith: A Theology of Making, he speaks out of his spiritual and his artistic practice.

But Fujimura also builds on three decades of reaching far outside his studio to evangelize on the necessity of art for human thriving and the call to shift from fighting over culture to caring for and nurturing it. He founded the International Arts Movement in 1992, which facilitates connections and communication between groups seeking to creatively and positively impact the culture, whether they are from the arts, music, business, education, or social change organizations.

Reviving Our Common Life in a World Struggling to Breathe

How to rebuke death and love your neighbors, in a pandemic and beyond.

WE KNOW WE intertwine with one another and the rest of creation in ways both material and symbolic: through blood and law, employment and play, through the full range of physical contact and social niceties, as well as loan papers, traffic tickets, and contracts. We sing a hymn in church, and the song swells into harmony, a gift of complexity and cooperation.

Through it all we breathe: Breathe in. Breathe out. My breath out mingles with your breath in. A communion of droplets. And so clusters of COVID-19 come not just in places of forced confinement—prisons, nursing homes, meatpacking plants—but after birthday dinners and choral practice, weddings and retirement parties.

“We’re all in this together” you might have heard as stay-at-home orders spread across the country; “the virus is the great equalizer.” After all, what could be more universal than breath? A pauper or a prime minister might breathe in a sufficient viral load to become critically ill.

Labored breathing

BUT THE CONDITIONS in which we breathe, the condition of our breathing bodies, and the conditions of the facilities that treat our bodies when breathing becomes difficult are rarely equal. Some people of great wealth have died from COVID-19, but many, many more of modest or little means have perished from it.

Societal inequalities of income and race incarnate as preexisting medical conditions, including diabetes, asthma, high blood pressure, and kidney and pulmonary disease, that increase the risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19. For example, in Washington, D.C., the bottom 10 percent of income earners have a rate of diabetes nearly 74 percent greater than the median. The wealthy can pay for better food and housing; they have less stress and exposure to industrial pollutants and more access to recreation spaces and health care. The lowest-paying jobs, many of which force people into overexposure to the virus, are disproportionately filled by those with options limited by racial bias and legal status. As Adam Serwer wrote in The Atlantic, “Black and Latino workers are overrepresented among the essential, the unemployed, and the dead.”

And the pandemic did not stop the other ways we deprive people of the breath of life: A neighborhood lynch mob stalks, films, and kills jogger Ahmaud Arbery but is not charged for months; police officers shoot Breonna Taylor in her own home during a botched raid; a white cop kneels on George Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds.

I breathe out. You breathe in. Before coronavirus, some people did that without a second thought. Yet every day others were struggling to breathe at all.