THIS SPRING, MY family and I were discussing what artistic representations of Jesus’ life have shaped our spiritual lives. For one son-in-law, it was Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, though he noted it is quite violent. For my husband and our adult kids, it was Jesus Christ Superstar. For me, it was seeing “Godspell” in Toronto in 1972 when I was 12. I vividly remember the wide-open energy that kept inviting new disciples into the group of Jesus’ followers, the circus-like performers bursting with enthusiasm, encouraging each other to creatively express what they were discovering together. It was physical, passionate, musical, hilarious. I looked up the musical’s history and discovered that my spirituality was shaped by legends of improv comedy, including Gilda Radner and Martin Short, who went on to be cast members of Saturday Night Live, and Eugene Levy, whose storied career continued this century in Schitt’s Creek.

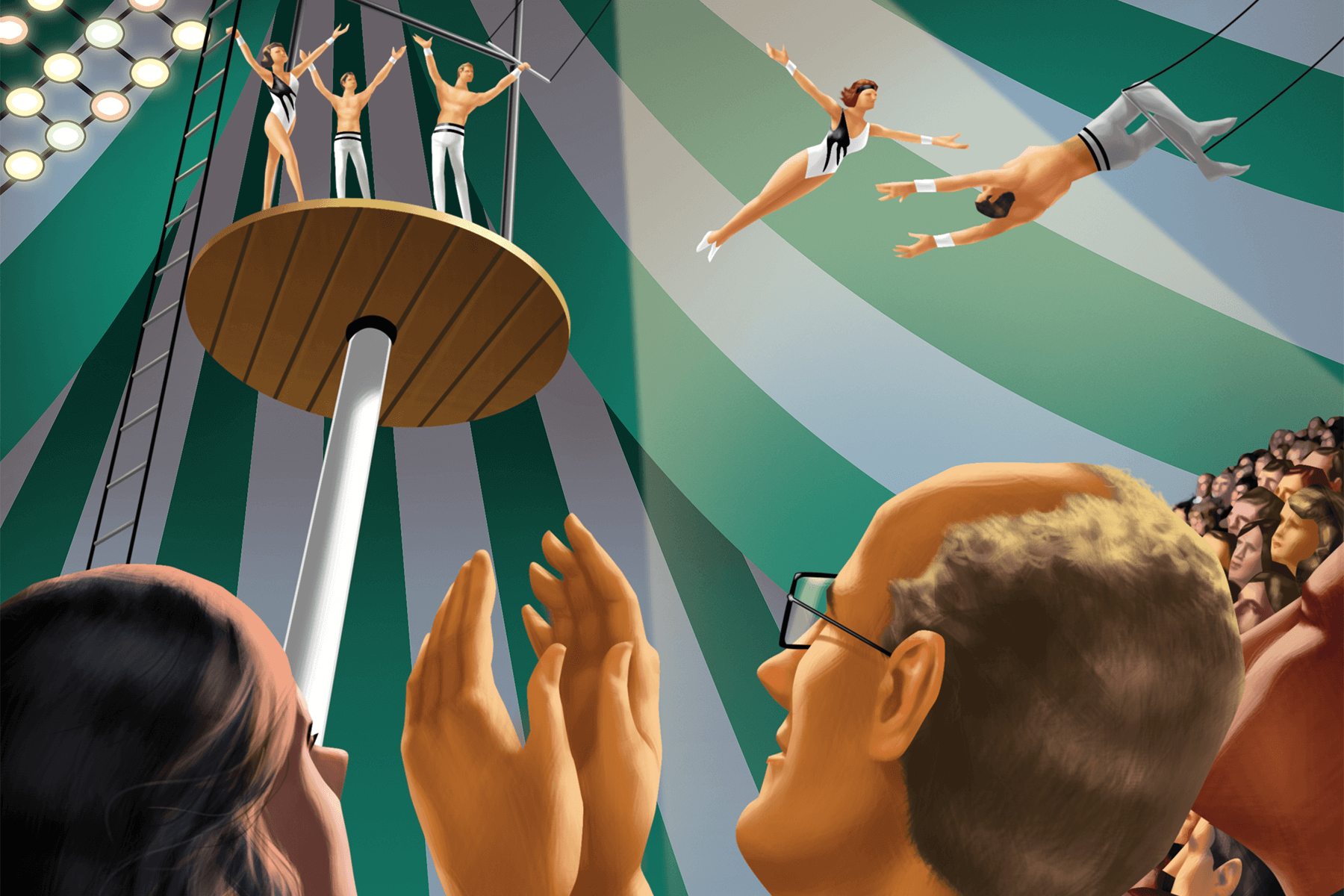

Perhaps that early spiritual orientation toward freewheeling motion, fun, community inclusion, live performance, and humor is why I appreciate theologian and author Henri Nouwen’s efforts to image our spiritual lives as daring, interdependent trapeze acts.

In 1991, Nouwen watched a trapeze artist fall, and noted that he was left in emotional turmoil. He wrote in his journal:

As Karlene flew down from the top of the tent to be caught by her catcher, I saw that something had gone wrong. My body tensed up as I saw Karlene missing the catcher’s hands and plunging down into the net. The net threw her body back up until it fell again and came to rest. The audience gasped but quickly relaxed when it saw Karlene straighten up, jump from the net, walk to the rope ladder and climb back up to continue the show.

After that I could hardly watch any more. I knew that the woman I had met for a few seconds at the concession stand was all right, but I was suddenly confronted with the other side of this air-ballet, not simply the dangers of physical harm, but the experience of failure, shame, guilt, frustration and anger.

nouwen2_1.png

An enfleshed life

NOUWEN, BORN IN 1932 in the Netherlands, was a Roman Catholic priest who taught groundbreaking courses in pastoral theology at Notre Dame, Yale, and Harvard. Then, in his mid-50s, he astonished his friends by moving to Toronto to join L’Arche Daybreak, an intentional community of people with and without intellectual disabilities. Nouwen died of a sudden heart attack in 1996.

From 1990, my husband Geoff and I and our three children lived at Daybreak with Nouwen. We were, like him, recovering academics and spiritual explorers, and thus became good friends.

In 2017, I was asked by Nouwen’s literary estate to see if I could find a book in the unfinished trapeze writings that had remained in his archives for more than 20 years. That project became Flying, Falling, Catching: An Unlikely Story of Finding Freedom, published in 2022. Like this article, the book is in two voices, Nouwen’s and mine, each with our own typeface.

Four years before he died, Nouwen wrote in his journal,

Many of my books no longer express my spiritual vision and, although I am not dismissing my earlier writing as no longer valid, I feel that something radically different is being asked of me. My many encounters with people who have no contact with any church, my contact with AIDS patients, my experience in the circus, and the many socio-political events of the past few years all ask for a new way to speak about God. This new way includes not only content but form. Not only what I say, but also how I say it should be different. What mostly comes to mind is stories. I know I have to write stories.

The first months of 1991 were discouraging for all who had spent decades working for peace. In January, Nouwen spoke to thousands in Washington, D.C., hoping to avert a Gulf war, but the next day “Operation Desert Storm” sent hopes for a more peaceful world crashing to the ground. By late spring, Nouwen’s book The Return of the Prodigal Son was completed and he was in Germany, taking a few months away from Daybreak to work on what would become Life of the Beloved. One day he went to a travelling circus with his elderly father, expecting only light entertainment. But watching the Flying Rodleighs trapeze troupe, his entire body responded.

As the three flyers swung away from the pedestal board, they somersaulted and turned freely in the air, only to be safely grasped by their two catchers. I somehow caught a glimpse of the mystery of being the Beloved: the mystery in which complete freedom and complete bonding are one and in which letting go of everything and being connected with everything no longer elude each other.

Other spiritual writers had been fascinated by the community of a travelling circus. Like Nouwen, William Stringfellow travelled with a circus and left an unfinished manuscript about it. Robert Lax became friends with circus performers and wrote a mesmerizing poem cycle about their ethereal, performative, prayer-like dedication. But Nouwen’s efforts were more personal.

Watching the Flying Rodleighs touched something deep in Nouwen’s body: joyful, wistful, excited, youthful, yearning. In his various notes, he circled around questions of how to acknowledge that initial response.

One thing I was certain of from the moment I saw the five artists entering the ring. They took me back forty-three years when, as a sixteen-year-old teenager, I first saw trapeze artists in a Dutch circus.

I do not remember much of that event, except for the trapeze. The trapeze act gave rise to a desire in me that no other art form could evoke: the desire to belong to a community of love that can break through the boundaries of ordinariness. …

I suddenly experienced feelings that were quite new for me: curiosity, admiration and an intense desire to be close, but also feelings of awe, distance and a strange sense of shyness. … now I felt that strange mixture of worship and fear that must make up the heart of an adolescent who has fallen in love with an idol on an unreachable stage.

Later, he dug into the implications of that physical experience:

The Flying Rodleighs teach me something about being in the body, being incarnate, being enfleshed. You know, the real spiritual life is an enfleshed life. So the Rodleighs are teaching me by who they are something more about what my deepest search really is all about.

‘The body tells a spiritual story’

Over the next few years, Nouwen became friends with the five trapeze artists. During another extended time away from Daybreak, he rented a mobile home and travelled with them for several weeks, witnessing their excitement over spectacular new achievements and frustrating public falls.

In an interview, he summed up where his new experiences fit into his life story:

When I met the Rodleighs and I saw their work and I got to know the trapeze world, again something really new happened. It was suddenly as if I discovered the incredible message the body can give. You know, it was like the university was the mind, L’Arche was the heart, but the trapeze was about the body. And the body tells a spiritual story.

Stop here. This should take your breath away: In 1994, at the height of the AIDS pandemic, a Roman Catholic priest who has known all his life that he is gay, that his body has desires and hungers that his church has consistently characterized as “intrinsically disordered” asserts with great enthusiasm, “The body tells a spiritual story.”

A few months earlier, Nouwen addressed the National Catholic AIDS Network’s summer conference in Chicago. By 1994, AIDS had become the leading cause of death among all people ages 25 to 44 in the United States. Looking out over the audience of caregivers who were daily facing so much death, Nouwen ached to encourage them. His audience whooped gleefully as he acted out his first encounter with the Flying Rodleighs. His favorite moment was when the flyer let go of everything to fly across the width of the circus tent, trusting both the teammate who helped launch them and the attentive catcher on the other side:

The only thing I have to do, Rodleigh said, is stretch out my hands. After I’ve done my thing — stretch out and trust, trust that he will be there, and pull me right back up. We have to love one another for that kind of trust. You and I are doing a lot of flying and I wish we do a lot more of it, and a lot of jumping and a lot of saltos and I hope we can do a few triples. It’s wonderful to see and you will get a lot of applause and it’s good. Enjoy it! But finally it’s trust — trust, when you come down from your triple, know that the catcher will be there.

The physical dynamic of flying and catching each other required close attention, Nouwen explained:

And then there was the intimacy thing. ... Rodleigh was making enormous somersaults in the air, then Jonathon catches him just at the last minute before he goes down. ... [T]hey catch each other on the wrists; they don’t catch each other on the hands — they sort of slide into each other’s arms, but there’s a kind of warmth there, a kind of safety, kind of a being held well. And, in fact, Jon and Karlene call their acts that they do right there at the top of the circus, cradling.

So that mutuality, being in touch with each other in that kind of way really speaks to me. And it’s a very profound sort of feeling.

nouwen3_1.png

Once after watching a practice, Nouwen climbed up to the high pedestal with the support of Rodleigh and his troupe, and swung from the trapeze, then dropped awkwardly into the net, beaming from ear to ear. If you are ever tempted to place Henri Nouwen on a pedestal as a “spiritual master” remember this scene: The pedestal is somewhere to launch from, not to preen, and artists are rarely alone on a pedestal.

Nouwen’s fascination with the Flying Rodleighs and their travelling circus community offers an imperfect yet joyful image of the interdependence that is essential to life together. He explained:

... I was just fascinated by their physical prowess. But I was as much fascinated by the group as a team. ... I realized from the very beginning that this group has to be really well together, and I saw that they enjoyed it, they really had fun doing it, and there was a kind of excitement in them that became very contagious for me.

The Flying Rodleighs were constantly renewing their performance and changing their act to be more challenging. They knew there would be disappointments and failures but took those in stride as essential to their creative development. Energized by the risk and excitement of the trapeze performances, Nouwen grew more courageous to consider new directions in his own life. He wrote,

... Since I am in my sixties, new thoughts, feelings, emotions and passions have arisen within me that are not all in line with my previous thoughts, feelings, emotions, and passions. ... I am more and more aware that Jesus died when he was in his early thirties. I have already lived more than thirty years longer than Jesus. How would Jesus have lived and thought when he had lived that long? I don’t know.

Letting Go

NOUWEN LET HIS physical and spiritual experiences change him. Perhaps that can speak to all of us negotiating our body’s complex desires and seeking out new ways to connect with others. If all these encounters are part of a spiritual story, we too can take courage to grow and expand. As Nouwen said to the HIV/AIDS caregivers conference, he had spent a lifetime gradually letting his judgments and boundaries fall “and suddenly you realize that your heart is expanding and there are no boundaries to that expansion.”

Just months before he died, Nouwen wrote in his journal:

I hadn’t expected that I would be so moved seeing the Rodleighs again. But I found myself crying as I saw them flying and catching under the circus cupola.

As I watched them in the air I felt some of the same profound emotions that I felt when I saw them for the first time with my father in 1991. It is the emotion hard to describe but it is the emotion coming from the experience of an enfleshed spirituality.

Nouwen found in the trapeze troupe a new image for how our enfleshed lives are always in motion. The artists figure out how to carry on together, through failures, falls, injuries, anger, and exhaustion. And that commitment creates something breathtaking and transcendently joyous, for both performers and witnesses.

Nouwen planned to write a book about the Flying Rodleighs that would capture not just ideas, but an experience. He imagined writing in a new genre — creative nonfiction or even a novel. He told friends this would be his most important book.

A year earlier, Nouwen reflected:

I have written many essays, reflections, and meditations during the last twenty-five years. But I have seldom written a good story. Why not? Maybe my moralistic nature made me focus more on the uplifting message that I felt compelled to proclaim than on the often ambiguous realities of daily life, from where any uplifting message has to emerge spontaneously. Maybe I have been afraid to touch the wet soil from which new life comes forth and anxious about the outcome of an open-ended story.

We are all in an open-ended story. In these times of fear and isolation, Nouwen’s trapeze story resonates, offering a way to reimagine our local and global interdependence and to continue the surprising spiritual story of our bodies in motion together.

When I saw the Flying Rodleighs for the very first time, it looked like everything that’s important in life … a world that had eluded me so far, a world of discipline and freedom, diversity and harmony, risk and safety, individuality and community, and most of all flying and catching.

Carolyn Whitney-Brown’s most recent book, Flying, Falling, Catching: An Unlikely Story of Finding Freedom, includes the Henri Nouwen quotes in this article, used with permission by Henri Nouwen Legacy Trust.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!