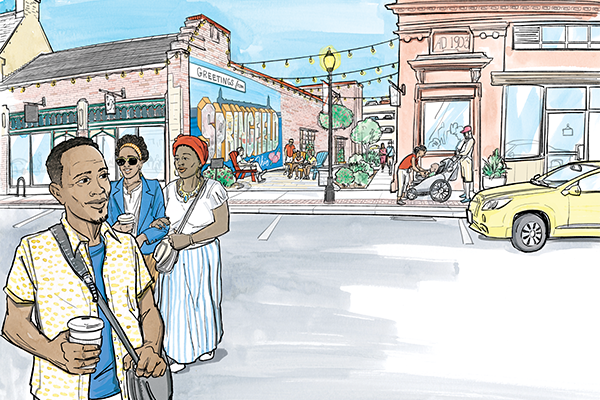

THIS TALE BEGINS with two Ohio politicians — one famous, the other relatively unknown outside Springfield.

For J.D. Vance, the city was a cudgel, useful in creating a media storm that would attract anti-immigrant supporters to his 2024 race for U.S. vice president. For religion scholar Warren Copeland, Springfield was home, a place to promote the policies that attracted immigrants to Springfield, where he served as mayor from 1990 to 1994 and from 1998 until his retirement in November 2023. Copeland was also a professor of ethics and director of the Hagen Center for Civic and Urban Engagement at Wittenberg University.

Read the Full Article