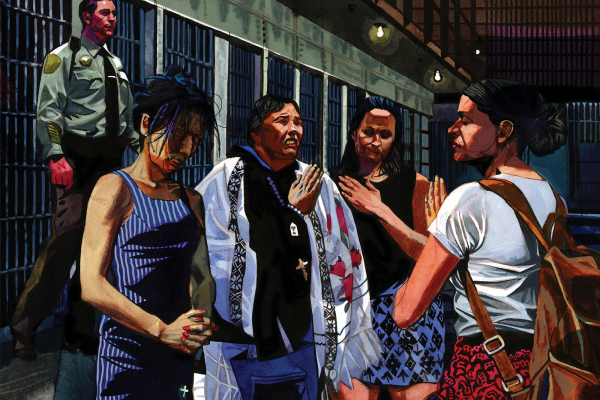

AFTER CARMEN AND her son, William, were set on fire by gang members and then rescued by a passerby, they fled El Salvador to seek refuge in the United States. In a caravan headed north through Mexico, by chance they met five family members: Carmen’s sister, Cecilia; Cecilia’s husband, Oscar; and the couple’s three teenage children—twin daughters and a son.

When they reached the end of their 2,800-mile trek to the U.S. border outside Tijuana, Mexico, the entire family surrendered to U.S. immigration officials.

That’s where, in November 2018, they met Monica Curca, founder and director of Activate Labs, a nonprofit organization focused on peacebuilding and human-centered “peace design.” The family members (surnames withheld for their safety) were among 30 immigrants for whom Curca’s organization provided advocacy and accompaniment and arranged financial sponsorship upon their entry into the U.S.

Once in the immigration system, the men and women were separated and sent to federal detention centers in Arizona and California; the men were detained for eight months and the women for five. William was separated from the family entirely, Curca explained. He ended up detained in Ferriday, La., in the former River Correctional Facility, a prison converted into an immigration detention center. Having been left for dead in El Salvador, he could have qualified for asylum—a form of legal protection for refugees who fear persecution in their native countries. But the activists working with him could not procure a lawyer, said Curca, and he was so miserable he chose deportation rather than prolong the suffering.

Read the Full Article