Feature

My grandparents supported Trump.

Their simple white house sits on the sprawling plateau between Joplin and Springfield, Mo., just around a bend in the country road where their church stands. It’s not more than a mile from the old farm, where my grandpa raised chickens and tilled the soil until his body would no longer allow it, as the man who owned the land had promised he could. To me, he’s always been Papa, but in that remote part of the Ozarks he’s known as the “chicken man,” a name in which he delights.

Papa has never been a very good businessperson. When at first he went to sell the fruits of his labor, he would put out a can and ask people to pay what they could. Eventually he fixed prices to things, but when the woman who was raising her grandchildren alone would show up, she knew that whatever she could spare was enough. “Don’t try to outgive the Lord, because you can’t,” Papa told me on countless occasions. In order to make ends meet, he used to work at the nearby quarry. Now he cares for the church building next door and, in exchange, the congregation lets him and grandma live in the house.

When I was in high school, I spent part of a summer on the farm, where I learned all sorts of things firsthand: that picking okra is sticky work, that spiders have an unfortunate affinity for tomato plants, and that unvarnished racism is still acceptable in certain quarters. It was the first and only time I remember meeting my great-grandma. She brought her new husband, Joe, with her, and at one point in the conversation he made clear he was not happy about the “Oreo cookie” families moving into the area. Still to this day, if you bring Joe up in the presence of my grandma, she’ll tell you she never truly accepted her mother’s last beau. He was too “mean.”

The religious ideas and practices of the Indigenous peoples of Bolivia, primarily Quechua and Aimara, flow like a subterranean stream through the country’s dominant Catholicism, particularly in La Paz, the most culturally Indigenous capital city in Latin America.

But evangelical Christianity, brought to Bolivia by European and North American missionaries more than 100 years ago, has also maintained a relationship with Bolivian culture—and that culture has shaped the church even as evangelicals have increased in numbers and influence.

Evangelical and other Protestant denominations, especially the neo-Pentecostals, have reached out to Aimara Indigenous communities, even while respecting fundamental components of Aimara ethnic identity. Thus while a chauvinism rooted in both national tradition and missionary evangelicalism dominates most male-female relationships in much of Bolivia, within Aimara neo-Pentecostal families, gender relations are more symmetrical.

Partly as a result of these cultural values, Indigenous women play important leadership roles within many neo-Pentecostal churches and organizations. They speak their own language in services and adopt symbols and rituals that come from their own Indigenous identity rather than European Protestant tradition. Whether it is recognized or not by outsiders, the Aimara identity proposes new ways of living and representing the Christian faith. Through the meeting of Aimara culture and neo-Pentecostalism, the assumption of male hierarchy is being questioned and subtly transformed.

THE WORLD INTO WHICH we preachers cast our voices is already the world claimed, sought, and being reclaimed by Christ. For a white preacher to risk talk about race is an act of faith in the transformative resourcefulness of the Trinity. When it comes to the great divine-human contest with our sin, including our sin of racism, God will have the last word: “Come to me” conjoined with “Follow me.”

While preaching can’t do everything, God has chosen preaching as weapon of choice in the divine invasion and reclamation of creation. Theologian Richard Lischer says that Martin Luther King Jr. “believed that the preached Word performs a sustaining function for all who are oppressed, and a corrective function for all who know the truth but lead disordered lives. He also believed that the Word of God possesses the power to change hearts of stone.”

Preaching is one of the means through which God defeats our natural narcissism.

Theology, not anthropology

Much of my church family wallows in the mire of moral, therapeutic deism, a “god” whom the modern world has robbed of all agency. Ta-Nehisi Coates begins his riveting Between the World and Me by announcing that he is an atheist. Between the World and Me is an honest but brutal, sorrowing, eloquent, hopeless lament for the intractability of American racism. Coates castigates those African Americans who speak of hope and forgiveness.

It must have been an odd thing, being the Holy Roman Emperor in June 1530, making the long trek to the Bavarian city of Augsburg to meet with a league of rebel states. But this is where Charles V found himself. Stranger yet, he was doing this not to convince these leaders to form a military alliance (though he was hoping to confirm their military fealty), nor to advocate for trade deals or relish the verdant Bavarian countryside.

Instead, the most powerful man in Europe had come to talk theology, with the hope that he could reunite a church fractured by the teachings of a rebel monk and a novice professor a mere 13 years earlier, in 1517. A monk who had since been condemned for heresy and treason in the 1521 Edict of Worms, but who—thanks to his ruler, Frederick III of Saxony—had nonetheless been hiding safely in plain sight ever since.

That wily monk, of course, was Martin Luther.

Thankfully, Luther and his supporters were relegated to the imperial backburner after the Diet at Worms, an imperially sanctioned assembly of the Holy Roman Empire, as global political matters and internal quibbling between testy royals kept Charles busy between 1521 and 1529. So the “Lutherans,” as they began to be called, took advantage of those years to thoroughly educate the priests and populace of Saxony about the most central of Luther’s teachings—the Doctrine of Justification: People “cannot be justified before God by their own strength, merits, or works, but are freely justified for Christ’s sake, through faith, when they believe that they are received into favor, and that their sins are forgiven for Christ’s sake, who, by His death, has made satisfaction for our sins. This faith God imputes for righteousness in His sight (Romans 3 and 4).”

LAST SUMMER, THE FUTURE of for-profit prisons seemed bleak. The U.S. Department of Justice announced it would begin phasing out its use of privately run prisons and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security quickly followed suit, declaring that it would reconsider its use of privately run detention centers. Stocks for companies that ran for-profit prisons plunged.

But then Donald Trump was elected president, and private prison stocks immediately soared. The nation’s largest prison company, CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America), reported a boost of more than 40 percent in the value of its shares. Given Trump’s promises to “create a new special deportation task force,” investors bet that privately run detention centers will play a key role.

And the investors may be right. Every year, DHS detains about 400,000 undocumented immigrants in 250 centers nationwide, and 62 percent of the beds in these centers are operated by for-profit corporations.

According to Maria-José Soerens, a licensed mental-health counselor serving undocumented immigrants in Seattle, there are two major problems with for-profit detention centers. First, for-profit centers are not held accountable to the standards that govern federally run centers. In her work in these centers, Soerens has heard complaints ranging from a lack of medical attention to inadequate opportunities for parent-child visitation; one young woman who was having suicidal thoughts was kept in solitary confinement until she told guards she was “better.”

But the deepest problem, explains Soerens, is that most detention centers only exist because corporations saw a “business opportunity.” Beginning in the early 2000s, for-profit prison companies successfully lobbied Congress to expand drastically the number of beds in the immigration detention system—a move that doubled the revenue of the two largest for-profit prison companies. In 1998, there were 14,000 beds available for immigrant detention; today, there are 34,000.

LONG BEFORE Boko Haram emerged in 2002, my home country of Nigeria was polarized along religious and ethnic lines by politicians who sought to pit one group against another. Disputes about religious freedom, resource control, and citizenship led to violent conflicts at the local and state levels. Many religious sites were desecrated.

Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa and seventh most populous worldwide, is fondly referred to as “the giant of West Africa.” It has the largest economy on the continent and is incredibly diverse in ethnicity and religion. Half of Nigeria’s population is Christian, living mostly in the southern part of the country, and the other half is Muslim, living primarily in the north.

In 2009, while I was pastor of a Catholic parish in Kano State, in northern Nigeria, a bloody confrontation broke out between the Nigeria Police Force and Boko Haram about 300 miles away in the northeast part of the country. Two years later, I was caring for eight families who had fled to the city of Kaduna, seeking safety from Boko Haram attacks. As I listened to their stories, I could not help but think of my own family’s displacement after riots in 1980 and 2002. Our congregation and my own family had been directly impacted by violent ethno-religious conflicts.

But the norm in the part of northern Nigeria where I grew up was very different from that. Christians and Muslims lived together as neighbors and friends. Young people bonded as they played sports with one another. Muslims and Christians exchanged greetings and attended one another’s naming and marriage ceremonies. We rejoiced and grieved together.

This included Nasiru, Ahmad, and Abdul, three of my Muslim neighbors who joined Boko Haram in 2009. They were attracted to Boko Haram because of their frustration with overwhelming socioeconomic inequality that had left them impoverished and unemployed. From their perspective, the ostentatious lifestyle of the political class indicated corruption, poor governance, and improperly managed resources. Boko Haram seemed to promise justice.

“We feel hopeful when the preacher reminds us that those who rob us of our livelihood will be judged and damned,” I remember Nasiru saying to me.

"REMEMBER YOU are dust, and to dust you shall return.” Each year the community of Jesus stands at the beginning of the season of Lent and recalls death, mortality, corporeality. We are dust. We are dying. And, as the pastor smears the mark of the cross on the foreheads of the faithful on Ash Wednesday, she says, “Remember you are dust.”

Such an awareness is where resurrection hope begins. It must. How can one celebrate resurrection hope without first understanding that we are dust and to dust we shall return? The act of marking ourselves with ashes is not morbid. Such rituals of death and resurrection give witness to God’s grace for both the dead and those who love them.

But what happens when there is no body over which to mourn?

In circumstances where a loved one’s body is lost, the pain and grief are magnified. A plane disappears over the depths of the waters, and bodies are never found. A person goes missing, and remains are never recovered. Whatever the circumstance, a funeral without a body is almost always a source of extra pain. Not only is a loved one dead, but the ritual act of tending to their body is taken away.

There are people in the United States, Mexico, and Central America who experience such trauma largely because of U.S. border policy. As people die migrating through the desert lands of the southern border of the United States, their bodies are literally returning to dust, and their suffering is largely invisible. Rather than receiving ritual care from family and community at the time of death, these immigrants die alone. Their remains are left in the desert, discovered only by chance.

A humanitarian crisis at the border

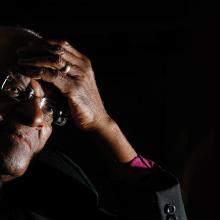

I FIRST HEARD Archbishop Desmond Tutu speak at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., sometime around 1987. It was at the height of apartheid in South Africa, and the world was just waking up to its horrors and organizing global economic sanctions.

Tutu spoke of an elderly woman he had met a few days earlier in Soweto. She told him that every night she got up at 2 a.m. for an hour in order to beg God solemnly for an end to apartheid. “I know we will win now,” Tutu told us, “because God cannot resist the prayer of that poor old woman.” With that, he burst into tears. Those tears of peace converted the thousands of us who crowded in to hear him. We had never heard such a witness for peace.

Later, I came to know him as a friend. During my 2014 pilgrimage to South Africa, I spent a morning visiting the great man at his foundation headquarters in Cape Town. First, we had Mass together with his staff; then he catered a brunch for me and my friends. He and I helped ourselves to a plate of food and coffee, then sat together by ourselves for an hour.

“We do not have the right to give up this work,” he told me. “Our sisters and brothers are suffering around the world, so we have to keep working for peace and justice till the day we die.” I was amazed to hear that he planned to leave the next day for Iran. He was in his 80s, in bad health, and relentless.

He spoke of the millions of squatters living in total poverty around Cape Town and elsewhere. “We have the ultimate First World wealth and the worst Third World poverty, the biggest gap between rich and poor in the world,” he said. “One percent of the money for war and nuclear weapons could feed and house these poor people. Sometimes I say to God, ‘What the heck is going on? Why don’t you do something?’”

FOOD DESERTS ARE low-income areas in urban or rural locations whose populations lack easy access to fresh fruit, vegetables, and other whole foods, usually because of lack of easy access to supermarkets. In 2010, the USDA reported that 18 million Americans live in food deserts, meaning more than a mile from a supermarket in urban/suburban areas and more than 10 miles in rural areas.

While suburban shoppers have more choices than ever, urban and rural Americans often lack access to quality food choices.

Karen Gonzalez, a church and community engagement specialist in Baltimore, works with immigrant populations. “For our clients, the challenge is that they work a lot, often two jobs, so getting to the grocery store and then cooking is a challenge,” says Gonzalez. “The other issue is that there are only two grocery stores in that part of town, and one of them is in the gentrified district—a Whole Foods. So clients often end up in bodegas or convenience stores, which have limited options and are more expensive.”

Food deserts in rural regions naturally raise different problems than those in urban areas. It is unsurprising that supermarkets are farther from people’s homes, but it can be overlooked that some rural low-income people do not own or have direct access to cars.

“Driving down a two-lane highway in rural Nebraska last spring, I passed a Native American man riding an old bicycle toward the nearby Omaha Indian Reservation,” wrote Steph Larsen on Grist.org. “We were at least seven miles from the nearest town, and he had four grocery bags bulging with food slung over his handlebars as he worked to climb a hill. I’ll bet a week’s worth of groceries that he wasn’t biking for the exercise.”

Sean Bear/ Shutterstock

IN A GIVEN YEAR, about one in five U.S. adults will experience mental illness of some kind. And though mental illness does not discriminate, African-American adults are more likely to experience serious mental health problems, but less likely to seek treatment, than white folks, due in part to the lasting effects of slavery, segregation, and other forms of race-based exclusion—effects that translate into socioeconomic factors such as poverty, homelessness, and substance abuse which are, in turn, risk factors for mental illness.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the factors that keep African Americans from receiving mental health services include a lack of health insurance, a distrust of the medical community, and conscious or unconscious bias among practitioners resulting in misdiagnoses. But NAMI also named another barrier to African-American mental health: the church. While one’s “spiritual leaders and faith community can provide support and reduce isolation,” explained NAMI, the church can also “be a source of distress and stigma.” The report noted that even when medical care is necessary, African Americans turn to their families, communities, and churches rather than turning to health-care professionals.

None of this comes as a surprise to Monica Coleman, a professor of constructive theology and African-American religions at Claremont School of Theology in Southern California. Throughout her new memoir, Bipolar Faith: A Black Woman’s Journey with Depression and Faith, Coleman navigates the challenges of race, gender, and the church as she heals from rape (committed by her then-boyfriend in seminary) and wrestles with a faith that ebbs and flows like the cycles of severe depression that began as she entered adulthood.

Sojourners assistant editor Betsy Shirley spoke with Coleman about mental health, social justice, and how the church might become a place that more fully fosters both.

JUST AFTER LUNCH, Eulalia Francisco shows Molly Hemstreet two pieces of white elastic bands, one of them slated for use as waistbands in a batch of woolen children’s pajamas being cut and sewed by the North Carolina-based, worker-owned cooperative Opportunity Threads.

Francisco, who had just two years of formal schooling in her native Guatemala, has noticed the elastic recommended for the sewing job is not the best choice for these pajamas. She recommends another elastic band.

Francisco is “our master sewer,” says Hemstreet, founder of Opportunity Threads, who agrees with Francisco’s suggestion and immediately orders the correct elastic.

After four years together, Francisco and Hemstreet, both worker-owners of Opportunity Threads, have a strong, trust-based working relationship. Hemstreet, an Episcopalian, earns the same wage as the other worker-owners and sees Opportunity Threads as having a spiritual component. “Before I met my husband, I thought deeply about going into cloistered work,” Hemstreet says. “I think of that whole thing of prayer and work, and that’s how I come here every day. We’re not making icons, but we’re doing work, and we do things in a joyful, prayerful way.”

The co-op grew from humble beginnings. After completing degrees in Spanish and Latin American studies at Duke University, Hemstreet moved with her husband, Francisco Risso, back to her hometown of Morganton, N.C., to open a Catholic Worker House. The local chicken plant hires many Latinos, but the work is hard and tedious, the pay not nearly a livable wage. So Hemstreet, with no formal training in business, explored the world of cooperatives, thinking it might be a good path to more meaningful and dignified employment for the Latino community.

DID MARY KNOW, on that puzzling and fateful afternoon when the angel Gabriel visited her, that she was about to join a line of mothers in Israel who would be remembered and honored within a tradition dominated by men?

Did she think of her forebear and namesake, Miriam, co-deliverer of her people from Egyptian slavery? Did Deborah, prophet and judge, come to mind—or Jael, the housewife who drove a tent peg into the brain of an enemy general? Had anyone told this nonliterate young woman about Huldah, the prophet and scholar who identified Deuteronomy as sacred scripture? Surely Queen Esther, who saved her people from a Persian pogrom, was known to Mary from the annual festival of Purim.

More likely Mary would have remembered women in Israel who gave birth to important men, such as Samson and Samuel. The late pregnancy of her cousin Elizabeth brought Isaac’s mother, Sarah, into view.

But her own premarital pregnancy may have reminded her more of Bathsheba, mother of Solomon. In this patriarchal culture, wives who could not conceive were disgraced and considered of little worth, but pregnancy before marriage could result in an honor killing. No wonder Mary fled to Elizabeth as the only person who might understand her unusual plight (Luke 1:39-45). Guided by the Holy Spirit, Elizabeth enabled Mary to turn her fear into a song of praise adapted from Hannah’s prayer after her son Samuel was born (Luke 1:46-56; 1 Samuel 2:1-10). God lifts up the lowly and brings down the proud.

If she pondered her place in Israelite history, did Mary also think of more-recent heroes? If Hanukkah was celebrated in Nazareth each year, she would have known how the second temple in Jerusalem had been rededicated to Yahweh after its desecration by the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV, 160 years earlier. Hanukkah acclaimed the successful Maccabean revolt and subsequent Judean independence; it also exalted Judith, whose name means “Jewish woman”; she saved Israel from destruction by beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes.

T photography / Shutterstock.com

FOR 18 YEARS, Ángel Pérez’s parcel sat barren. His remote village in southern Mexico offered no employment, and his only resource—his land—had been depleted by decades of overuse. When his son Manolo grew old enough, Manolo emigrated north to find work, following the footsteps of half the community and leaving his father behind. Desperation led Ángel to drink. Bottle in hand, he stared down his two options: leave his home, his community, and his land, or resign himself to a life of scarcity. (Ángel and Manolo are pseu-donyms used for privacy reasons.)

In 2014, a surge of Central American refugees streamed north through Mexico. They traveled under the stars through drug cartel territory, slipped past human traffickers, and arrived at the U.S. border pleading for sanctuary.

THE FIRST TIME I saw John Rush was during a 2015 political forum at a local high school in Columbus, Ohio. Rush was running for city council, and though all the candidates had been invited, many didn’t bother to show up. As Rush began his presentation, he brought empty chairs up on the stage and made some quip about how the chairs were waiting for the absent candidates. The joke was not cryptic or unkind; it drew gentle laughter and applause from the audience. I didn’t know what party Rush belonged to, but I was captivated.

As a longtime pastor in Columbus, I’d seen a lot of candidates for city council. All of them had the usual rash of promises: They would create jobs; they cared about “the least of these”; they listened to the hearts of the people. Voting for them would help change the world.

But Rush seemed different. Though he was a white man with a military-style buzzcut speaking to a room full of African Americans, he didn’t seem shy or uncomfortable. He didn’t make a lot of promises. He just talked about how he knew what people were going through, and his knowledge seemed genuine, like he had “been there.” He mentioned growing up really poor, in Appalachia, and how that felt. He joked about being an evangelical who cared about more than the wedge issues of abortion and same-sex marriage. He talked about knowing how to listen to and appreciate all kinds of people. Nobody, it seemed, was an outsider to him.

Rush eventually lost his bid for election, but the more I learned about him, the more fascinated I became. He spent his early years in a trailer park surrounded by racism, joined the Marines, and later returned to the Midwest to help found a nondenominational church in Chicago. He now runs a business that helps people who were incarcerated or caught in human trafficking reintegrate into society. He was an ordinary person, leading an extraordinary life.

THE COLD STUNG my skin, even though I’d rubbed a protective layer of balm on my cheeks. Our breath mingled and condensed in a cloud of vapor. Doug and I grabbed hands and ran across the parking lot. He opened the driver’s door, and I scooted across the bench seat as quickly as I could. My long wool coat did not slide well. Doug climbed in after me and cranked the ignition, which caught immediately. His mustard-colored Volare was dilapidated, but a good starter. Who cared if the passenger door no longer opened? This was January in Minnesota.

Wordlessly, we listened to the engine rumble. Time was running out, and yet another church had failed to meet our hopes. The sermon had been lackluster. There’d been zero women in leadership. Nothing had clicked. We wanted more than a wedding venue; we wanted a church home.

My son Samson stood in front of our pew. One of the men in the congregation knelt and fixed his bow tie. The Sunday morning sunlight was streaming through the stained glass and the skylight. I hugged friends.This is going to be good, right? I prayed . Please, Lord, I hope we’re doing the right thing.

On Aug. 13 we renamed and blessed my son, Samson Red Gabriel. Samson is transgender. That week we had gone to court to legally change his name and gender, and that week he turned 10. That Sunday held the joy of five baptisms, all the hilarity and devotion that goes along with that, and this incredible rite that had never been done before in the Episcopal Church. As far as we know, nothing like it had been done for a child in a mainline church before, period.

“AMERICA FIRST” is not a new mantra. While Donald Trump used the phrase during his campaign and in his inaugural address, some of its most telling roots are in the America First Committee of the 1940s, which advocated staunch isolationism (and less explicitly, anti-Semitism) and sought to prevent the U.S. from entering the second World War.

For Trump, the phrase is connected to economic wealth. “I’m ‘America First,’” Trump told The New York Times in a pre-election interview. “But you can’t make America great again unless you make it rich again.”

When Trump declares he will make “America” first and rich, he’s clearly not referring to everyone in the U.S. “America first” is a battle cry for the privileged, those who already reap tremendous benefits off the backs of the marginalized. When Trump wants America to be first by being rich, he means white Americans at the helm of corporations and lobbies, whose success comes at the expense of others.

‘Prosperity breeds amnesia’

Christianity is rooted in a gospel narrative that urges its adherents to strip ourselves of attachment to worldly treasure and the egoism of being first (see Matthew 20:16). Despite that, Trump’s most supportive base is among white evangelicals. As Frederick Douglass put it, “Between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference.”

Why has so much of modern (white) U.S. Christianity—with its scriptures of the “first shall be last” and in light of hard-earned historical lessons of slavery, the Civil War, and the civil rights movement—aligned itself with values so antithetical to Jesus’ message? Perhaps some of the answer can be found in an insight from Walter Brueggemann’s Sabbath as Resistance: “Prosperity breeds amnesia.”

EARLY LAST YEAR a Hyattsville, Md. man arrived home to find police cars and crime scene tape on his walkway. He learned that his younger sister had accidentally overdosed, and the coroner had been summoned to rule out foul play. The man wanted to enter the house, view his sister’s body, and perhaps say his goodbyes. But the police wouldn’t allow him inside.

“I could see when he started walking up the walk that he was unhappy,” said Rev. Stephen Price, who police called to the scene. “He and the officer were having a very tense conversation,” said Price, pastor of First Baptist Church of Hyattsville.

So Price intervened. “He’s mad and the officer is feeling strained,” Price later explained. “I said, ‘Walk with me a minute.’” The man vented his frustration, but eventually calmed. Price explained what the police needed to do and persuaded the man to stand with his family while police finished their work in the home. In the interim, Price promised to be a go-between for the man and the officers until the body was released. Shortly after, the family was allowed inside. They invited Price to join them, and he led them in prayer.

For the family, it was a day of tragedy and grief. For police, it was a daily reality of their job: dealing with death and navigating mistrust from the community they serve. Yet, for a nation where interactions with law enforcement all too often end with violence, it was a small step in the right direction: The police responded to a call, tensions were diffused, and no one got hurt.

“I DIDN'T KNOW YOU WERE MEXICAN?” “Oh, your dad is from Puerto Rico?”

These are probably the most common replies I received throughout my childhood, when someone found out my last name. At one point, exhausted of explanations, I started to reply in the affirmative to whatever Latin American country was chosen.

However, the response to my name has changed in the last 10 years or so. Now when I tell someone my father is from Costa Rica, the most common reply is about a vacation they took with their family, or that they know someone who plans to retire there. Pura vida.

However, this small Central American country did not represent a paradise for my father as a child. His childhood was rough. When my father was around 8 years old, one year shy of my oldest son’s age, he was dropped off at a stranger’s home. He worked for this family for almost a decade, a few of his relatives visiting on rare occasions. There is no nostalgia in the messy details of his recollection.

By his own estimate, God has since blessed him: He is now father, foreman, pastor, and, recently, grandfather. The U.S. was a refuge, a place of opportunity, for the man with a fifth-grade education who grew to read St. Augustine for pleasure and instruction after dinner. I grew up in that man’s shadow.

The hardships he experienced as a child were denied his two sons: We had a happy childhood. I learned to accept my mundane, middle-class biography, realizing my script would not contain the dramatic details of my father’s life. My Christian conversion story produces a yawn in even the most-sympathetic listener. My “rebellious” teen years—a manufactured mistreatment molded by myself—paled in comparison to the real struggles that my father went through.

One of my favorite pictures of my father when he was younger is a photo of him with his abuela (grandmother). I never met her. Out of the few black-and-white photos of my dad that we have, this is the only one I can recall that he is smiling. He decided to take the Jimenez name because of his abuela. He eventually left Costa Rica in the late 1960s; after his abuela died, nothing tied him to the country.

In the U.S., he heard the command to “take up and read” to discover that the New Testament was like no other book. After the New Testament, he returned to St. Augustine, but read him with different eyes. He discarded numerous religious and philosophy books that left his soul empty. But not St. Augustine.

THE PARABLE OF the mustard seed is beloved, but also dangerous. Like most beloved scripture passages, its revolutionary impact on its original hearers has been weakened over time, replaced by sentimental fondness.

Originally, the parable would have promised restorative justice to the economically afflicted, an undermining of borders and boundaries to the religious purists, and a warning against exulting oneself. Part of the genius of Jesus’ parables was to speak on multiple levels to multiple groups with the same words.

Noticing Jesus’ audiences for this teaching is profoundly important. Jesus was teaching in a gathering that included at least some religious leaders (Pharisees and scribes; see Matthew 12:38).

Leaving the house in which he was speaking, Jesus went down to the water to address an even larger crowd (Matthew 13:1-2). In his audience for the parable, there were a mix of religious leaders and ordinary people, including farmers of the fertile Galilean hills. Jesus used their respective expertise to provoke the different groups.

Tenant farmers

Jesus said the reign of God is like a mustard seed that a farmer took and sowed in the field. The agricultural workers who heard Jesus would have scoffed at this.

No one would ever sow mustard seed into any ground one owned. First-century farmers in Galilee with any agricultural acumen knew that mustard is a weed that reproduces rapidly and spreads indiscriminately. It chokes out other more-valuable crops and ruins the land for other uses. No farmer who loved the land would have planted a single seed of mustard in the field.

First-century farmers knew from Jesus’ story that the planter must not be a farmer who cared about the land, but someone who didn’t know anything about stewarding the land.