Kate Ott (kateott.org) is an assistant professor of Christian Social Ethics at Drew Theological School in Madison, N.J., and the author of Christian Ethics for a Digital Society.

Posts By This Author

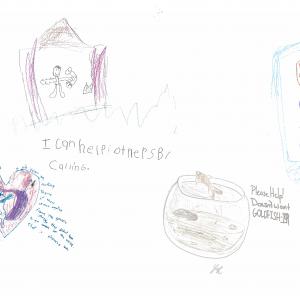

Loving Your Neighbor During a Pandemic, According to Kids

Editor's Note: As part of her piece "Using the Love Commandment to Talk COVID-19 With Your Kids," Christian ethicist Kate Ott collected drawings and quotes from children engaging in the topic of loving your neighbor during this health crisis. Here's what they had to say.

Using the Love Commandment to Talk COVID-19 With Kids

As adults are forced into major social and work-related changes, we can quickly lose patience with our children, forget their perspective matters, and resort to “just do it”-type responses. I want to encourage parents to take a deep breath and invite children into a new way of being in the world shaped by COVID-19. Children are morally resilient and creative when we give them the chance. So, how can we talk with our children about this pandemic? Let’s use the love commandment as our guide.

Shouldn't We Just Trust Christian Leaders?

Power is dynamic, so accountability should be too.

INCIDENTS OF SEXUAL misconduct in faith communities shine a spotlight on issues of power in congregations.

As important as recognition, prevention, and intervention are for ending sexual violence, faith communities have significant work to do on routine, everyday abuses of power.

The way faith communities distribute labor and educational responsibilities, as well as committee assignments and financial obligations, often fall along stereotypical gender, class, and age lines. These mundane misuses of power in church settings desensitize us to recognizing serious boundary violations when they occur.

Faith communities assess power differentials and concurrent risks to determine policies that provide checks and balances on power imbalances. For example, individuals who are ordained have more power because of their level of education, professional status, and theological notions of representing God or a tradition. Adults have more power than youth because of social experience, economic means, or physical ability. In these dyads, power accrues to the individual with more resources. This is generally a solid starting point when assessing power differentials and then minimizing risk by creating practices of accountability. However, we rarely occupy one identity or one role when participating in congregations.

The Internet Endureth Forever

...and what that means for Christian forgiveness.

FRANTICALLY GRABBING last-minute items, I rush out the door to get my middle-school son to his pregame warm-up. “Oh, don’t rush; it will only take us 25 minutes to get there,” says my son. Surprised, I question where he got that information. Looking up from his phone, he replies, “Google sent a notification on my phone since my calendar has the game with location.” With some marvel in his tone, he remarks, “Every morning Google Assistant tells me how long it will take the bus to get to school.”

Humans have always shared information with each other, but the advance of digital media altered the time and geographic constraints that once shaped our historical patterns of communication. This transition ended the “Gutenberg era,” a period of human communication marked by a dependency on print, authorship, and fixity, and launched us into an era of communication marked by openness, collaboration, and easy access to information.

Despite the rapid pace at which we churn through this information, our new communication styles are also shaped, paradoxically, by permanence. Every share, post, or comment is archived, creating an online trove of information that identifies every person and their connections: where we get our news, what we look like, what sports team or social causes we support, who “likes” our church on Facebook, and, in my son’s case, our current whereabouts, our travel route, and destination points.

The internet is forever

In the world of digital ethics, the “endless memory of the internet” has recently attracted a lot of attention. How do we live in a world that increasingly does not forget?

5 Ways to Teach Kids About Justice

How do we help the youngest members of the church understand the gospel's call to love God and to love our neighbors as ourselves?

CristinaMuraca / Shutterstock

READERS OFTEN ASK US: How can I incorporate a hunger for justice into my child’s spiritual formation? How do we help the youngest members of the church understand the gospel’s call to love God and to love our neighbors as ourselves? Sojourners asked five Christian parents engaged in various forms of justice work to share their best tips for helping children put their faith into action. Here’s what they said. - The Editors

1. Look for Teachable Moments

by Kate Ott

MANY PARENTS FEEL unprepared to talk about sex or faith with their children. I was one of those parents until I realized age-appropriate sexuality information could empower my children and keep them safe. I also realized that teaching my kids about sexuality meant more than talking about “sex.” After all, if I didn’t talk to my kids about how Christian values of love, justice, and mutuality guide the care of our bodies and our relationship choices, who would?

So rather than planning for a single “big talk” or waiting until I know all the answers, I practice parenting through teachable moments. For example, in our house we talk about how clothing choices and hygiene reflect our thankfulness for our bodies as part of God’s good creation (including remembering to brush teeth!). As a parent, when I take a picture of my kids, I ask them for permission before posting it on social media; this encourages thinking-before-posting and consent as an active yes. And when we’re watching TV or listening to a song in the car about attraction or a relationship, I ask questions like: How would you feel in that situation? Do you think that person values their body? Does that seem like a mutual decision/relationship? Is that kind of love balancing God, neighbor, and self? In the short conversation, I always say something like, “Being in a relationship takes a lot of work and requires communication, honesty, commitment, and mutuality.” This models how to use one’s values to assess relationship choices.