Arts & Culture

In his seminal work Mythologies, French philosopher and critical theorist Roland Barthes announces that “Myth is a type of speech.” And not simply any type of speech, but a dangerous kind. Myth is problematic, he says, because it allows a fictional brand of naturalism to subsume history. It creates a false narrative that the way things are is the way things are meant to be, leaving ample room for injustice to flourish.

Recently, the playwright Jeremy O. Harris tackled one particular section of American mythos: education. And, in typical Jeremy O. Harris fashion, his exploration is complicated.

I went to see Harris’ fantastical play “Yell: A ‘Documentary’ of My Time Here” in a state of fear and excitement, wondering what dirty laundry he would air about my then-future intellectual home.

“AFTER THE END came the Beginning.” This is how we enter the world of Ling Ma’s debut novel Severance: in the liminal space between end and possibility. In a narrative that alternates between aftermath and memory, we find a stark reflection of our present.

Protaganist Candace Chen works for a book production company, and her specialty is the acquisition of Bibles. Tedious office work. She has lost her parents, recently left a relationship, and lives alone in Manhattan when news of a spreading illness—Shen Fever—erupts. The fever begins in China, in a region that produces the Gemstone Bible, one of Candace’s specialty Bibles. Before and during this outbreak, work, for Candace, is at once sustenance and distraction.

Who can live outside capitalism? Jonathan, Candace’s ex, certainly tries. But that is not the life Candace wants—or, rather, that is not the life her immigrant parents raised her to want.

WHEN YOU WALK into the theater, you feel you’re at an American Legion community center, with hundreds of framed male portraits lining the walls. It’s a little daunting. And then Heidi Schreck as a young woman arrives to give her speech, “What the Constitution Means to Me.”

She explains that this is how she raised her state college tuition: winning speech and debate competitions about the Constitution, taking on the male power structures that surrounded her. Our 230-year-old Constitution is a wordy and tricky document, to say the least, and Schreck steps up to it with delightful rhetoric, full presence, and comic genius. She shows us why we should be in love with it and why we should uphold it.

But then things shift, and she comes to us, blazer tossed aside, as a now-40-something woman with wisdom and deep questions. The second half of the play takes us on a whirlwind history of the document with all of its problems, especially how this male-conceived, male-written constitution suppressed and continues to suppress women. Sitting quietly at the side, and sometimes explaining the rules of the speech debate competition, is an American Legion representative, played on Broadway by Mike Iveson.

I am Peter at Gethsemane

where I wake to oak

branches suspended,

spinning like hair in water.

Flora’s night

blanched, a prophet’s

chanting, every caesura’s

quiet steeping, transfiguring

grief to alms.

The film challenges Western beliefs about familial and individual responsibility, as well as the often-unrecognized personal sacrifices we make for the ones we love.

This film tells the story of Bryon Widner's exit from white supremacy and how love redeemed his life.

A few days ago, I gathered with my two Potawatomi sons on our couch to watch Molly of Denali, a cartoon that recently premiered on PBS starring a young girl named Molly who is an Alaska Native (specifically, Gwich’in/Koyukon/Dena’ina Athabascan). This show is the first of its kind in the history of the United States.

Just under a hundred days before their first World Cup match (in which they would score a record-breaking 13 goals), every member of the team filed a class action, gender discrimination lawsuit against the U.S. Soccer Federation. The timing of the announcement conveyed that the 23 other teams in the tournament would not be the only opponents of the USWNT this World Cup.

Why wouldn’t they drop by, stare up

approvingly at the point of the minaret?

Perpetual connoisseurs of the loving work

of centuries, the stacked stones, nails pounded

until synagogues, temples, shrines

little houses of worship rise from the land.

THE U.S. HAS BEEN on a war footing since at least 1939. Undergraduate students today have never known a world before 9/11, and even their instructors (I was born in 1983) have never known a peaceful America. The Cold War era that preceded our own was enormously bloody in places such as Lebanon, Vietnam, and Afghanistan—and in all these countries, American intervention played a role.

During the Cold War, permanent war footing seemed like more of a threatening novelty than a grinding inevitability. The time played host, therefore, to a global and surprisingly influential peace movement. The Politics of Peace tells the movement’s dramatic story of both ideals co-opted and maybe even betrayed and ideals that shaped our world and might be worth recovering.

WHITE EURO-AMERICAN Christianity is dying, according to Miguel A. De La Torre, and from his point of view, its death is necessary. It has distorted the gospel with Euro-American nationalist ideals that benefit white communities at the expense of communities of color—heretical beliefs grounded in fear and exclusion, rather than love. In Burying White Privilege: Resurrecting a Badass Christianity, De La Torre deconstructs Donald Trump’s abundant evangelical support. In doing so, he offers guidance on how Christians can move forward.

Whiteness lies, he explains. It lies about the superiority of particular beliefs and nations. And this superiority complex has led to a lot of violence being done under the name of Christianity, including displacement, slavery, and genocide.

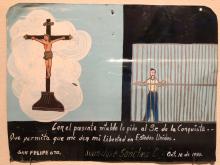

These retablos reflect on the faith that people had to begin the journey of migration, entering a foreign land. Often leaving family and home into the unknown, on a journey that is fraught with peril but also promise. Young fathers and mothers, children of families who will pray for them daily as they go. As the exhibit description mentioned, these retablos "depict a side of migration usually not told in statistical reports or even in detailed interviews of migrants."

YET ANOTHER BOOK about climate change. What could it possibly say that we haven’t already heard?

Plenty, it turns out.

David Wallace-Wells’ extraordinary and chilling book The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming gives an overview of the overwhelming scientific consensus that the planet is warming and changing at rates never seen before. But the real value for its readers are the 100 brutal pages of excruciating details about what life will be like if they do not quickly make extraordinary changes to their energy consumption. Wallace-Wells’ central message is that we are living in a time hotter than any other time humans have ever lived in, and we cannot go back in our lifetimes. And looking forward is nothing short of terrifying.

APPROPRIATELY ENOUGH, The Saint of Lost Causes —the new Justin Townes Earle album—has an Orthodox icon of St. Jude on the cover. In Catholic lore, St. Jude is the patron saint of lost causes and desperate cases. But if a person can still turn to a saint for intercession, the cause isn’t entirely lost. The desperate act of prayer implies at least a sliver of hope for grace and mercy, and that’s mostly where the people in Earle’s new batch of songs are: down to their last desperate prayer but still hoping.

At the beginning of the album, in the title track, Earle lays it out, singing: “Now it’s a cruel world / But it ain’t hard to understand / You got your sheep, got your shepherds / Got your wolves amongst men.” Over the course of the next 11 songs, we see the world mostly from the point of view of the sheep. We hear from some fracked-out citizens in “Don’t Drink the Water” who are growing increasingly restless as some oil company hack keeps claiming that their poisoned land and water, and the occasional earthquake, are all an “act of God.” Later, in “Flint City Shake It,” a streetwise Michigander fills us in on how General Motors assassinated his still-resilient hometown. Then there’s the junkie desperado of “Appalachian Nightmare” who hopes God can forgive him at the moment of his death.

Shelter and Storm

Seeking Shelter: A Story of Place, Faith, and Resistance is a 30-minute documentary on the personal history of the late Christian activists Daniel Berrigan, William Stringfellow, and Anthony Towne. Using firsthand accounts, the film follows their work for civil rights, social justice, nuclear disarmament, and environmental action. Seekingshelterblockisland.org

WHEN I TRAVEL to a city, I find art museums and their masterpieces: “Sunflowers” in Amsterdam, the “Prodigal Son” in St. Petersburg, “David” in Florence. Van Gogh, Rembrandt, Michelangelo. These are masters, according to some cultural imagination.

But it wasn’t until this past April that I encountered an Asian master and masterpiece: Katsushika Hokusai’s “Under the Wave Off Kanagawa.” The print is better known as “The Great Wave”—you know, the Apple wave emoji. Why is this the first Asian masterpiece that I’ve seen?

BEFORE THEY ARE hip-hop performers, educators, and poets, the Peace Poets are a family. “It’s been a development of a brotherhood,” Frank Antonio López (aka Frankie 4) says of the group’s formation. López and Abraham Velazquez Jr. (aka A-B-E) met when they were 3 years old. Enmanuel Candelario (aka The Last Emcee) was introduced to the pair in grade school and introduced to Frantz Jerome (aka Ram 3) in high school. Candelario would go on to meet Luke Nephew (aka Lu Aya) at Fordham University in New York.

Much of the Peace Poets’ foundational development occurred in Harlem at Brotherhood/Sister Sol, a leadership and educational organization for black and Latinx youth. It was there, López says, that the Peace Poets were “politicized through art.”

"The reactions are full spectrum from shock to upset to being angry, but not angry at what I'm doing, angry at the stark fact that this could be a reality," the artist, who does not reveal his real name, said in an interview on Monday.

Do you remember where you were four years ago when you heard the news?

Good theater contains a strain of that gospel antidote, that powerful tradition of trying to name and recognize our demons and human propensities. The earnestness in story that pairs what we believe with what we do, can serve as a way to handle truths about ourselves and our dealings that make us uncomfortable. Often written off as fluffy and as a less effective means of activism, the tradition of plays and musicals has the power to stage an inner confrontation in real time, asking the audience to contend with a hard truth or recasting a social norm we seldom question.