Arts & Culture

There’s no such thing as an objective critic, or objective criteria by which any of us could judge a movie. The question is whether the critic, or the audience, is able to be honest about the criteria they are using. So I’ll say something I’ve said before: By my sights, the purpose of art is to help us live better, and the best cinema occurs when technical and aesthetic craftsmanship operating at their highest frequencies, and a humane concern for the common good, kiss each other.

All of them returned to the South’s frontline struggle for racial justice.

Today, the United States and Iran are two countries on the precipice of war with ruling elites who quote Rumi.

The film humanizes the two popes, while exploring their different ecclesial emphases: church as an inward-facing haven from the world or church as an outward-facing sojourner.

IN THE EARLY days of Hollywood, Japanese-born actor Sessue Hayakawa (1886-1973) was an icon. In the context of racist U.S. policy and increasing nativism in Hollywood, he was arguably the first non-Caucasian actor to gain international fame and the first person of Asian descent to become a leading man in the movie industry.

His overall career, however, is a story of race’s shadowy relationship with success. Orientalism, Yellow Peril, and America’s fear of Japan both helped and hurt his career. The Catholic Church’s eventual oversight of Hollywood also played a part in his troubles. The only way Hayakawa thrived in the industry was by playing into the structures of racism that set up his stardom.

“Such roles are not true ...”

IN 1915, WITH actress Fannie Ward, Hayakawa had the first on-screen interracial kiss.

Well before the Motion Picture Production Code outlawed interracial romance in 1930, the silent film The Cheat (1915) shows Edith Hardy (Ward) as a wife who takes money from the Red Cross, loses the $10,000, and then struggles to repay her debt. As she reels from the news of her loss in a semiconscious state, an acquaintance, Hishuru Tori (Hayakawa), assaults her and steals a kiss before she comes to her senses.

The silent film continues as Hardy describes her debt to Tori. Tori writes a check from his exorbitant wealth—he is described by title cards as a Japanese ivory trader—but not for free. He expects something from Ward.

When Hardy goes to repay Tori after her husband makes a hefty return on an investment, Tori locks the door and assaults her a second time. He brands Hardy with a circular seal; after she falls to the ground, the camera focuses on the stark black mark on her white shoulder.

The branding scene caused uproar in the Japanese American community. A Japanese newspaper in Los Angeles denounced Hayakawa, his sinister character, and the character’s appearance as a harmful stereotype. (Hayakawa reportedly had asked Cecil B. DeMille, the director of The Cheat, to change the clothing and mannerisms of his character, but DeMille disregarded him.) The backlash was enough for the film to be re-released in 1918 with Hayakawa’s character changed to a “Burmese king,” presumably because the studio believed Burmese people would have less volume to their voices of dissent.

“Such roles are not true to our Japanese nature ... They are false and give people a wrong idea of us,” said Hayakawa in 1916. “I wish to make a characterization which shall reveal us as we really are.”

RIAN JOHNSON'S FILM Knives Out wastes no time setting up the murder mystery that powers its plot. In the very first scene, famed mystery writer Harlan Thrombey (Christopher Plummer) is found in the library of his mansion, his throat cut. Harlan’s family is shocked. His Latina caretaker, Marta (Ana de Armas), Harlan’s closest confidant, is devastated. The police think it’s a suicide. Private detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) thinks otherwise.

The mystery of Harlan’s death may be the plot of Knives Out, but as the story progresses, it’s clear that the film is actually about something else.

Bootstrapping—the idea that one can achieve success purely through hard work and determination—is touted in most areas of public life, from business to education to politics. White Americans particularly love to claim that we’ve risen from tough circumstances while making it harder for less-advantaged populations to do just that.

In Knives Out, the bootstrapping myth is everywhere. Harlan’s children are proud that their dad built a publishing empire. Harlan’s daughter Linda (Jamie Lee Curtis) tells Blanc that she, too, created her own business from the ground up. But, of course, those stories aren’t the whole truth. Linda would be nowhere without the hefty loan she got from her father. Harlan himself may have worked hard for his success, but as a white man, there’s no doubt his path was easier than it would have been for others.

Let My People Go

Mary Lambert, the Christian, queer, Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter featured in Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’ “Same Love,” sings of trauma and triumph in her latest album, Grief Creature. Abuse, rape, shame, depression: Lambert faces them all. “Sometimes I call it drowning,” she says. “Sometimes I call it Moses.” Tender Heart Records.

That damage of war has been put on full display in films before, leaving many audiences wondering about the purpose of war films. Many films often placed strictly into the categories of being anti-war or glorifying war but 1917 evades easily falling into either category. When addressing this categorization, screenwriter Krysty Wilson-Caines made sure to note that she had no desire to glorify war.

IN HER LATEST novel, Petina Gappah reimagines the death of Scottish missionary and doctor David Livingstone, focusing on his African servants, the names history forgot. They are Christians, Muslims, healers, porters, women, and children: a family of strangers who band together to carry Livingstone’s body, marching more than 1,500 miles in 285 days, so his remains may be claimed in Bagamoyo, Tanzania, and returned to England.

Every name on this trip holds stories that could occupy a novel of their own. To encompass them, Gappah employs two distinct narrators: Halima and Jacob Wainwright.

Halima, the doctor’s cook, is known for her sharp tongue, which ridicules the caprice of men and repeatedly tells of her youth as a sultan’s slave. In the early days of the journey with Livingstone’s body, Halima mourns the doctor, whom she calls “Bwana (Master) Daudi,” like a paternal figure. Though the men on the journey take credit, she is the one who proposes a way to preserve the doctor’s corpse for the long road ahead.

But Halima’s love for the bwana does not prevent her from noting his contradictions. She wonders why he would leave his family to search for the source of the Nile, argues with his colonial perception of a children’s game, and questions how a man who condemns the slave trade would have one of their company whipped.

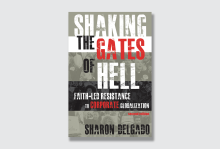

JESUS HAS THE first word in Shaking the Gates of Hell: his warning against serving Mammon as master. We are on notice that this book on analyzing and resisting the assaults of global economy will do so by way of biblical spirituality. To put it more precisely, Sharon Delgado’s critique will rest on a foundational theology of the principalities and powers.

The book begins in a jail cell, where she was in lock-up following arrest in 1999 as part of the massive demonstrations known as the Battle in Seattle, which effectively shut down meetings of the World Trade Organization. Shake those gates. Rooted in action, prayers in such places can seed entire volumes. Also to say: This book is punctuated with personal stories, pastoral and political.

That Fortress Press has seen fit to publish this updated edition is testimony to its staying power as a substantive primer. There are new sections on “algobot” market investing, racial profiling, mass incarceration, and the path to permanent war. Climate predictions that seemed dire in the first edition already need to be updated, as timelines shorten and catastrophic realities set in.

Structurally, the first third of the book focuses on “the undoing of creation” (a phrase of William Stringfellow’s defining “the fall”). Much of that is devoted to the wounds of Earth, and then to human wounds by toxification, technology, impoverishment, and violence.

Sojourners: Why write a book on sex and faith and shame?

Matthias Roberts: Many of us who grew up within purity culture have rejected the strict, moralistic guidelines around sex and sexuality we were raised with, but aren’t sure what beliefs we do still hold. As a counselor, I noticed coping mechanisms that aren’t necessarily the mosthealthy ways to work with our sexuality. I hope to name what those unhealthy coping mechanisms are and chart a way forward.

What is sexual shame? Shame is a core response that we have that makes us turn away. When things within our sexuality make us want to turn away from either ourselves or other people, we get sexual shame. Sexual shame affects us relationally—and not just within our sexual relationships. It can look like secrecy and avoidance: We’ve been taught we can’t express sexuality outside of particular contexts and yet most people are, so we hide that away, lie about it, or pretend it’s not there.

1. I knew, but didn’t know—extent, sprawl,

continent-wide bird with great shadow-wings

hovering over a whole nation’s knife-opened birth—

talons and curved-hook raptor’s beak coming

for my heart, which is history,

which shields itself and hungers

as though truth were a flock of season-following geese

from whom I choose how many to bag,

how many a season requires. So many

moments sound like gun-shot—

sound cracking the ear with its own hammer,

pummeling some dark priest-hole in every mind,

fists on doors, slammed hatches on ships,

iron coming down so hard on a deck it loses its clang,

a skull punched against echoing wood, snapped branches,

snap of a jaw-trap around leg bone.

An eagle cannot feed its young its young.

Compassion. Curiosity. Courage. To author Talia Carner, a writer needs these three qualities to tell a good story — and they are on full display in Carner’s latest historical novel, The Third Daughter. Based on “The Man from Argentina,” and the tales of Tevye the Dairyman and his daughters by Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem, the book tells the story of the hundreds of Jewish girls from Eastern Europe who were trafficked by the Jewish pimps union, Zwi Migdal, and brought to Argentina and Brazil in the late 19th and early 20th century.

A door closing tight, shutting out an image of a man sitting on an elegant chair, taking the hand of a subordinate: a firm instruction to keep out. Another door half-open, behind which another man in physical decline sits, alone and afraid of the dark. Two cinematic perspectives on two doors. The first forms the conclusion of Francis Coppola's The Godfather, as Michael Corleone is effectively enthroned as a demonic king. The other may become comparably iconic, as Martin Scorsese's The Irishman’s Philadelphia mobster Frank Sheeran does the most he can to feel regret, to feel anything, after a life of theft, killing, and nihilism masquerading as protecting the ones he loves.

Though the inaugural Madeline L’Engle conference felt like a safe haven as we gathered in the cozy glow of art, and fellowship, we were all still very aware of a similar sense of imminent evil in our country and the world at large. We are no longer in the Cold War, but the uncertainty of the impeachment hearings, of uncontrollable wildfires at home and abroad, of the refugee crisis and the hardening of hearts at the borders hang over us daily. Just as is often asked these days about Fred Rogers, we at the conference found ourselves murmuring, “What would Madeleine L’Engle think? What would she do?”

Bong-Joon-ho’s film is about what happens to those living below sea level when the rain comes.

“WHY AM I here?” The question echoed in my head as it had on countless prior occasions. It seems that I cannot participate in a meeting or conference about Christian community development, social justice, or racial reconciliation without the question emerging at least once. As an African American woman, I am frequently reminded that these spaces are not my home. I am an outlier: I am neither White nor male, and I don’t fit neatly into any of the typical Protestant boxes. I am too evangelical to be mainline, too mainline to be fully historical Black church, and too historical Black church to be evangelical. Sometimes I even feel too interfaith to be Christian. I am often alone in a room full of people—the only woman of color and even the only African American woman. The conversations in these spaces are often overtly patriarchal, dismissing women’s experiences and expertise. These groups think diversity is achieved if they include men of color and White women, both of whom make pronouncements about race and gender that are assumed to capture everyone’s experiences but that exclude those of women of color. I am often forced into the position of being the “Yes, but” voice. It is soul-wearying. And yet I—we—stay.

IF ALL THE hungry people in the U.S. were gathered into one state, its population would roughly match that of California. According to the USDA, 40 million Americans are food insecure. This means 1 in 8 Americans lack sufficient food to live a healthy life.

Our children fare even worse. In the richest nation the world has ever known, 1 in 6 children will at some point this year be left with a growling belly, wondering where their next meal is coming from, and when. In South Texas, where Jeremy Everett works to end hunger, 1 in 2 children face such dire straits.

According to Everett, to tackle a problem as large and complex as hunger, individual trust, commitment, and community buy-in are crucial. They are not enough, though: Widespread collaboration is also required. Communities must join forces with other communities, nongovernmental organizations, businesses, and government at all levels. They must pool their resources and knowledge and coordinate their efforts.

ROSE MARIE BERGER doesn’t know it yet, but through her tour-de-force poems in Bending the Arch, she has become a holy woman of many nations. Among my own people, she would be called one of the alikchi, a sacred healer, a doctor of the people, a woman who can restore balance to lives that have been shattered. She does this through the strong medicine of words.

Berger, poetry editor and a columnist for Sojourners, describes Bending the Arch as “ethnopoetic documentary poetry.” “Ethno” because it speaks with the accents of a dozen different cultures: European settlers, Chinese miners, Native American leaders. “Poetic” because it uses a cat’s cradle of language from different moments, people, and realities. “Documentary” because it covers a vast scope of America’s manifest destiny history, symbolized by the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, which is depicted on its cover. All these are contained in layers of history, one on top of another, until the spiritual sediment of Berger’s meaning begins to become clear.