Jul 3, 2019

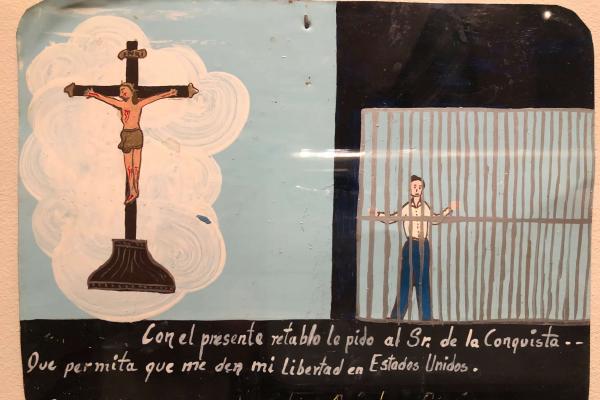

These retablos reflect on the faith that people had to begin the journey of migration, entering a foreign land. Often leaving family and home into the unknown, on a journey that is fraught with peril but also promise. Young fathers and mothers, children of families who will pray for them daily as they go. As the exhibit description mentioned, these retablos "depict a side of migration usually not told in statistical reports or even in detailed interviews of migrants."

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login