Arts & Culture

IT WAS APRIL 2017, just a couple of months into the Trump era, and our family was at our parish’s Easter vigil—a three-hour-plus Saturday night service that begins with a bonfire and includes the baptism and confirmation of those who’ve spent the last year preparing to enter the church. Our parish has one of the largest Hispanic communities in the area, so our Easter vigils are always bilingual.

By the time we distributed communion, it was around 11 p.m., and as I watched the procession of my Catholic neighbors go by, I was struck by the sight of the brown-skinned men, husbands and fathers in their 20s and 30s, coming down the aisle with sleeping babies cradled tenderly in their arms. They were contradictions to the president’s words: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best.”

The recent Netflix documentary series Living Undocumented follows eight families through all nine circles of U.S. immigration hell. The immigrants in the series are from Honduras, Mexico, Colombia, Laos, Mauritania, and Israel. But all of them, even the Laotian guy who picked up a drug felony in his troubled youth, are people any sane country would welcome. And our government is doing everything it can to send them away.

Ordinary Heroes

The 10-part podcast City of Refuge tells the little-known story of a French village that resisted the Nazis during World War II and saved 5,000 refugees. A model for collective strength, City of Refuge shows what happens when ordinary people act in extraordinary ways. Waging Nonviolence.

Black Brits

Girl, Woman, Other , the Booker Prize winner by Bernardine Evaristo, explores the U.K.’s deep roots of racism and how 12 black people in Britain—11 women and a gender nonbinary person—navigate their multifaceted identities. Black Cat.

You may know 別告訴她 by its English title: The Farewell.

The second feature film from director Lulu Wang stirred audiences with a story from Wang’s family. In the film, the main character, Billi, joins her family in China as they convene a wedding as an excuse to say goodbye to her grandmother, who has a terminal illness but does not know it.

At the wedding, the grief of imminent loss peeks through the haphazard nuptials. In some of the film’s most memorable moments, toasts take heartrending turns into breakdown, and a drinking game provides space to drown sorrows with alcohol and laughter.

In the game, Billi’s family is seated at a round table. Chanting in Chinese, one person repeats a phrase while flapping their arms like wings, then looks to another person, who takes over the chant. Whoever makes a mistake takes a shot. The general mechanics of the scene are clear, but unlike most of the film, there are no English subtitles.

ANNE LISTER WAS a woman, but she was certainly no lady. That’s clear from Gentleman Jack, the HBO television series based on Lister’s life, which spanned 1791 to 1840. Gentleman Jack covers her daring ascent of the Pyrenees, macabre interest in human dissection, penchant for risky business dealings, and delight in women—both high-born and low—all while she gads across Europe in a man’s greatcoat, cravat, and waistcoat. We know of Lister’s exploits because she wrote them down, in a secret code of her devising. In between her romps, she recorded everything from the weather and her breakfast to her deepest thoughts and cares. All told, she wrote some 5 million words over 26 volumes. Lister’s diary is so important to the understanding of the private lives of British women in the 19th century that it has been called the “lesbian Dead Sea Scrolls.” “I love and only love the fairer sex,” Lister proclaims in its pages, “and thus, beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any other love than theirs.” But while Lister may have been largely unconventional for her time, she was a rather traditional 19th-century Anglican. Gentleman Jack’s focus in its first season (which concluded in June 2019) is Lister’s desire to find a wife and marry her in the eyes of God—something she accomplished by force of will and a prescient faith that, to quote Lin-Manuel Miranda, “love is love is love.”

I am the border agent who looks

the other way. I am the one

who leaves bottled water in caches

in the harsh borderlands I patrol.

I am the one who doesn’t shoot.

I let the people assemble,

with their flickering candles a shimmering

river in the dark. “Let them pray,”

I tell my comrades. “What harm

can come of that?” We holster

our guns and open a bottle to share.

In his Neighborhood of Make-Believe, with simple hand puppets with complex internal lives such as Daniel Striped Tiger, Prince Tuesday, and Ana Platypus, he did something profound. Rogers and his collaborators on the show listened intently to children, created routine and a safe, sometimes magical place where they might be understood, affirmed, and cherished.

For those of us who perhaps didn’t always get the emotional support we needed at home, it was a gift that helped shape who we are as adults, parents, and grandparents.

The film also gets right Rogers’ deep belief in God and Junod’s persistent doubt. Junod was raised a Catholic but fell away from the church. For a while he attended a Presbyterian church, but now does not. He is still interested in the spiritual, he says, and a lot of that stems from his relationship with Rogers. This summer, as publicity for the movie was heating up, Junod recovered 70 emails he exchanged with Rogers from an old laptop, many of them about theology.

Motherless Brooklyn, writer-director-star Edward Norton’s adaptation of Jonathan Lethem’s 1999 novel, is confident enough in its own scope to begin with Shakespeare, and it certainly backs up this confidence with an argument. A quotation from Measure for Measure invites us to reflect on the nature of power: “O! It is excellent to have a giant’s strength, but it is tyrannous to use it like a giant.”

Every moment feels true to life, and the literal waves — the peaks of emotion and the sinking tragedies — carry viewers up and down, a rhythm as unpredictable as it as captivating. WAVES is a film for 2019, that does not shy away from the music and actions of teenagers living in 2019.

Jesus is King is the most pointed and concise album of Kanye West’s catalogue. He had a clear goal in mind — to praise Jesus for all that he has done for Kanye. Kanye approaches that goal and this album with blinders on, trampling over his hypocrisies of his own life and the way he views the word of God.

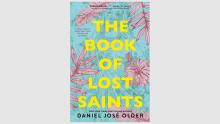

Daniel José Older’s novel is a powerful meditation on love and betrayal in times of revolution.

Kanye West draws upon the storied history of black communal worship and gospel music.

HANNAH ARENDT SAID we can ask of life, even in the darkest of times, a “redemptive element,” and art can be that—an affirmation of right, light, truth, some beleaguered beauty. But note well: Art is no escape from the problems of the world but, rather, a repurposing, a resistance. And, of course, this phenomenon of violence into art can go both ways. Michelangelo’s bronzes, including his colossal papal statue of Pope Julius II, were melted down into cannons and other weapons during the French Revolution. It’s our choice.

Here are four artists who chose to turn trauma—civil war, natural disasters, apartheid, and female genital mutilation—into sights to behold.

Ralph Ziman, South Africa

Designed and put into service in apartheid South Africa in the 1980s, the so-called Casspir, a mine-resistant and ambush-protected vehicle, has been subverted. Says South African artist Ralph Ziman: “The Africanization of the Casspir seemed to take away the terror it once evoked ... people felt comfortable to approach it, touch it, and share their stories and memories.” He elaborates on his intention: “To make this weapon of war, this ultimate symbol of oppressing ... to reclaim it, to own it, make it African, make it beautiful, make it shine.”

Born in South Africa in 1963, Ziman grew up in a strict system of institutionalized racial segregation and political and economic discrimination—“apartheid,” which translates in Afrikaans to “apartness.”

“I have vivid memories,” he says of his first sighting of a Casspir. It was April 1993. Charismatic leader Chris Hani had been gunned down outside his house in a Johannesburg suburb by a white nationalist. The artist drove to the funeral and saw columns of Casspirs descending the dusty streets; heavily armed police fired tear gas, shotguns, and automatic weapons. More of the same occurred the next day in Soweto, where police and army units parked their Casspirs along the highway and exchanged gunfire with members of the African National Congress. “Tear gas and smoke burned our eyes and into our memories, along with the sight of armed men on the Casspirs ... for me, covering this beast with beads is catharsis,” says Ziman.

Blessed Are the Merciful

In Clemency, Emmy winner and Oscar nominee Alfre Woodard plays Bernadine Williams, a prison warden preparing to oversee her 12th execution. Viewers enter Williams’ mind as she grapples with executing another prisoner. A film with emotional weight and pertinent themes, Clemency raises important questions.

Neon

Save for the sun, the nearest star

is more than twenty-five million

million miles away.

What has a single star

shining in Bethlehem

to do with us?

IT HAPPENS TO just about all of us who, in our early adulthood, commit ourselves to a life of globally conscious idealism. We run off to join a cause, maybe commit to a volunteer project for a year or two, come home, and find ourselves overwhelmed by how to create lasting change in a broken world.

Christian writers Jim and Linda Hunt struggled with this question in 1998, not so much as young people but as middle-age adults, after their daughter Krista perished in an accident in Bolivia. Krista and her husband Aaron were three years into their marriage and six months into a three-year service project teaching literacy and microenterprise with the Mennonite Central Committee, when the bus they were in plunged off a ravine.

IN THE ADJUNCT UNDERCLASS, Herb Childress addresses a pressing issue of justice in higher education: the mistreatment of more than half the nation’s college instructors. Childress explores the making of adjuncts—contract workers (like rideshare drivers) who teach on a class-by-class basis, earning a fixed rate that is less than half what a “full-time” professor would make for the same work. Most receive no benefits and no assurance of future classes.

After a boom in college attendance 20 years ago and the foolish assumption that population growth and a robust economy were constants, the higher education system is scrambling to make up for greedy mistakes. The price for those mistakes is being paid by teachers, who should be concerned about educating students, not struggling for survival on subsistence wages. And so the real cost is to education itself.

The Adjunct Underclass is masterfully written and thorough, covering budgets, expansion, accreditation, hiring, and the ambivalence of tenured faculty. Adjuncts offer horror stories of scraping by while waiting on empty promises of an established position. These stories demand moral outrage.

A YOUNG WOMAN armored in her blazer, caffeinated and tethered to the phone line of a Manhattan hedge fund, hardly seems the optimal audience for an artist whose work hinges on stillness and contemplation. And yet—if you saw an enormous book of James Turrell’s installations perched on your desk, how could you not open it?

That was my reasoning as I re-encountered Turrell’s oeuvre, third cappuccino in hand. I didn’t know it then, but Turrell’s artistic framework would provide a new way to think about New York City. More specifically, his clarity of vision vis-à-vis light and space stands in contrast to a city replete with people the critic John Berger describes as “resigned to being betrayed daily by their own hopes.”

The city that allegedly never sleeps is wonderful in many ways, but by the end of my tenure there I was increasingly overwhelmed by the hustle, noise, and collective anxiety around, well, everything. Temping at a capital investment firm, while a welcome paycheck, was not my idea of meaningful work, and sitting like a bird in a glass tower, detached from the people below, even less so. Reaching for Turrell’s book, which was likely deemed politically neutral enough for an office setting, was an act of desperation and belief that I could still be surprised, awed even. And I was.

TERRENCE MALICK HAS long been associated with spirituality. The director’s philosophy background, poetic style, and love of nature results in art that urges viewers to engage deeply with the world: Ask difficult questions, doubt, and believe.

But A Hidden Life, Malick’s latest, may be the most faith-oriented film yet from the director of The Tree of Life and The Thin Red Line. Through the story of World War II-era martyr Franz Jägerstätter, Malick explores what it means to wrestle with Christian conscience during rising xenophobia and violence. Jägerstätter (played by August Diehl) was an Austrian farmer executed for refusing to swear loyalty to Hitler. For Malick’s purposes, he becomes an audience surrogate as he encounters his community’s reactions to the Third Reich, and later a Christ figure.

Malick spends significant time establishing the beauty of Jägerstätter’s life before the war. We’re given glimpses of his village and farm, witness romantic moments with his wife, Franziska (Valerie Pachner), and fall in love with them and their home.

IN 1948, A HERMIT was made known to the world by another hermit. Like many Christian holy men, the Jewish-born Catholic contemplative and poet Robert Lax had his early spirituality enshrined in a book: The Seven Storey Mountain, the bestselling autobiography authored by his friend, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton.

“He had a mind naturally disposed from the very cradle to a kind of affinity for Job and St. John of the Cross,” Merton wrote about Lax. “And I now know that he was born so much of a contemplative that he will probably never be able to find out how much.”

Better known to many for what was written about him than for what he wrote (and he wrote a lot), Lax, who died in 2000 at age 84, wanted, according to his archivist Paul Spaeth, “to put himself in a place where grace can flow.” For Lax in the 1940s, New York City was not such a place. Though he worked with the poor at Baroness Catherine de Hueck’s Friendship House in Harlem, and had enjoyed jazz with Merton, he balked at the gaspingly fast pace and materialism of the city. He was also unhappily employed at The New Yorker.