Arts & Culture

“FENGBE, KEH KAMBA BEH. Fengbe, kemu beh. We have nothing but we have God. We have nothing but we have each other.”

Like the voice of the wind, this song pervades the vivid landscape of Wayétu Moore’s debut novel, in which the Liberian-born writer explores the early days of Liberia, in the 1840s, through three characters: Gbessa, June Dey, and Norman Aragon.

In She Would Be King, these three impossible lives (and a country) emerge out of slavery, violence, and exile. Death eludes and “mocks” Gbessa, of the Vai people, who constantly suffers the pain of dying without its relief. Born on a cursed day, Gbessa grows up under house arrest until she is exiled. Alone in the forest, torn from her family and people, she sings, “Fengbe keh kamba beh. Femgbe, kemu beh.” The “we” of this song haunts the reality of Gbessa’s situation, and to offer a glimpse of the big picture, Moore writes: “The words ascended, joining the traveling wind, and sometimes it was as though someone were singing with her.”

And someone was. Across time, language, and distance. Ol’ Ma Famatta sits in the moon, and the slave once known as Charlotte whispers comfort in the wind as if to say loneliness is not forever, as if to promise Gbessa that she is not alone.

IN ITS THIRD chapter, Hermanas asks: “What is your beautifully empowering narrative that may influence your hermanas [sisters] around you and those that are to come after you?” In the most wonderful way, the book’s three authors—Natalia Kohn, Noemi Vega Quiñones, and Kristy Garza Robinson—share their own stories to answer this essential question. Through the writing, they become the Latina mentors and role models many Latinas want and need, as many of us have no such examples in our communities.

What comes through these pages is how much these writers embrace their identities as Latinas, how much they love their communities, and how deeply they’ve experienced God through their identities.

They rightfully make no apology for writing this book for the many Latinas that may have had similar experiences with dominant white Christian culture. They read, interpret, and apply the Bible from the perspective of not just Latinx culture, but the specific experiences of Latinas who often find themselves doubly marginalized by racism and sexism and, thus, unheard. The authors provide examples of biblical women such as Esther, Deborah, and Hannah who embrace their ethnicity and challenges to become leaders and teachers in their spheres of influence, whether directly or indirectly.

WILLEM DAFOE is my favorite onscreen Jesus, and since The Last Temptation of Christ’s release three decades ago, he’s been indelibly associated with that role. His Jesus was a corrective to the over-mysticized versions in epics such as Ben-Hur and The Greatest Story Ever Told, which portray Jesus as a kind of magician instead of a person.

Dafoe’s Jesus (which is also the Jesus of novelist Nikos Kazantzakis and Paul Schrader, who adapted Kazantzakis’ work for the screen) is a serious attempt at grappling with the human questions his story demands. This Jesus is a breathing, sweating, sleeping, dancing, agonizing, raging Jesus: a political Jesus who prefers a donkey to a revolution; a compassionate Jesus who struggles to figure out his own needs amid the burdens of the world; a thinking Jesus who doesn’t emerge from the womb with a fully formed philosophy but learns by experience, scripture, and prayer.

Fictionalized Jesuses are, of course, like any other Jesus: We see all the Jesuses we’ve ever met through the lens of our own experience. The light of Willem Dafoe’s Jesus (not to mention his astonishing portrayal of Vincent van Gogh in the recent masterpiece At Eternity’s Gate) is more useful to me than the “magician” versions because I’m not sure I can learn much from superheroes.

Let the Beat Drop

Hamildrops, a series of 12 singles inspired by Hamilton, includes a range of artists (Black Thought, The Regrettes, Sara Bareilles) singing or rapping on topics such as racism, domestic abuse, and recovery efforts in Puerto Rico. The last released song features gospel legend BeBe Winans and Barack Obama. Hamildrops.com

Tackling Health Disparities

How Neighborhoods Make Us Sick: Restoring Health and Wellness to Our Communities offers an innovative, Christ-centered vision for approaching health disparities in inner cities. Drawing on professional experience in community development and public health, Veronica Squires and Breanna Lathrop outline achievable goals for promoting health equity. InterVarsity Press

IN ITS MOST BASIC FORM, theater is about transformation: altering voices, mannerisms, appearances, and scenery until what was becomes unrecognizable. Theater is also about resurrection: an empty stage brought to life, an untold story come alive. And no theater better embodies resurrection than Mosaic Theater.

In fall 2014, the Edlavitch Jewish Community Center (JCC) of Washington, D.C., forced its theater company, Theater J, to cancel the critically acclaimed Voices of the Changing Middle East Festival due to pressure from JCC donors upset with the festival’s controversial nature. Ari Roth, Theater J’s artistic director, protested the end of the festival’s groundbreaking interfaith dialogue and was subsequently fired. Afterward, he established Mosaic Theater, of which he is the founding artistic director.

“In a way, it was a very dramatic, abrupt, and even violent birth,” Roth told Sojourners. “It involved collateral damage, harsh words, a firing, accusations of censorship, a divorce. There was a rupture.”

Mosaic Theater was born from broken relationship—yet today it stands as a testament to inclusion, reconciliation, and renewal. Located on H Street in D.C.’s Northeast quadrant, Mosaic is a thriving fusion community committed to producing high-quality, socially relevant art in an uncensored environment. It is now in the middle of its fourth season, titled “How Hope Happens.”

“Moving to Mosaic meant we would lose Judaism but keep the prophetic piece. It would be multifaith, a mosaic of faiths united by common values. And the top value was a belief in the power of art to transform and transport people and communities to new places,” said Roth.

I know you believe you are doing God’s work when you ask me

“Are you a Christian?” and instantly retort to my “No” with “Why not?”

I know you do not know how the hairs stand up on the back of my neck

when first you question my failure to embrace Jesus as my Lord and Savior

and then interrupt with that world-weary “Ahhh ...” as I say,

“Well, my mother’s family was Jewish— ”

If it needs doing, will it

if it needs dying, kill it

Don’t spend more time disclaiming than proclaiming

Do the work and let the work speak for itself.

If you can, say yes. If you can’t, say no, and make sure your WHY can stand before God

Myth-making is something the creative forces at Cave Pictures Publishing, a new comics publisher, are fascinated by. The publisher aims to use the medium’s possibilities in ways that bring together faith-oriented audiences who may be new to comics, and long-time fans of the medium looking for thematic depth. Wylde, a western-themed horror comic, is currently available on ComiXology. The Light Princess, an adaptation of the George MacDonald fairy tale, arrives in February.

While accepting a Golden Globe last night, actress Regina King made “a vow” to hire “50 percent women” on every project she produces in the next two years.

SYRIAN. AMERICAN. Muslim. Woman. These distinctions of religion, geography, and gender are sometimes considered worlds of their own, but rapper Mona Haydar is used to navigating between them as a daughter of Syrian immigrants to the U.S. who grew up in Flint, Mich. Her experiences of embodying a multicultural identity in a country teeming with bigotry are the basis of her new EP, Barbarican, a collection of powerful songs that challenge rigid notions about who gets to consider themselves American and who gets left out and called a barbarian.

Haydar emerged onto the music scene in March 2017 when she released a colorful music video for her song “Hijabi (Wrap My Hijab).” The video featured her, eight months pregnant, surrounded by hijab-clad women as she rapped about diversity and the freedom to practice hijab, an often-criticized tradition in the West. Billboard named “Hijabi (Wrap My Hijab)” one of the best protest songs of 2017, creating anticipation for more music from Haydar. With Barbarican, Haydar has delivered a searing follow-up.

Opening with the line, “If they’re civilized, I’d rather stay savage,” Barbarican celebrates the colonized, specifically those who have suffered from the racist equating of “brown” and “black” to “backward” and “barbarian,” and “modern” to “white.”

In the song “Barbarian,” Haydar examines the ways in which colonialism seeps into the minds of people of color, teaching them to hate aspects of themselves. With dynamic beats and catchy refrains, she creatively subverts colonialism by using its own words against it. Haydar even fights stigma surrounding mental health, by wrestling with both her experience of postpartum depression in her song “Lifted” and her reaction to the suicide of a friend in “Suicide Doors,” which features singer-songwriter Drea d’Nur.

SEXUAL ABUSE is not about sex: It’s about power.

At least that’s what Ona, the female protagonist of Miriam Toews’ novel Women Talking, insists in the aftermath of one of the most horrifying incidents of sexual abuse in recent history. Toews’ book is based on true events: Between 2005 and 2009, more than 100 Mennonite women and girls in a remote community in Bolivia were raped at night by what they believed were demons punishing them for their sins. These attacks were perpetrated by men in the community who used modified animal anesthetics to drug and rape the women in their own homes. The victims’ ages ranged from 3 to 65.

Toews’ novel is a fictional account of a conversation between eight of these women. As Toews’ story develops, the rapists are imprisoned, other men of the community have gone to bail them out, and the women—illiterate and unaware of what lies beyond the boundaries of their community—gather to decide between three courses of action: do nothing, stay and fight, or leave. As they debate, their dialogue is infused with theological discussions and surprisingly dark humor. These conversations give insight into the community’s culture, religiosity, and the ways that each woman copes with her personal grief.

Oddly, the voice of August Epp, the meeting’s minutes taker and the only man present, dominates Toews’ narrative. This story about women resisting a patriarchy gives an unexpected amount of attention to a man.

BEFORE WE GET to the best movies of 2018, let’s talk about the most memorable moments of this year in cinema. Neil Armstrong casting his daughter’s bracelet into a canyon on the moon in First Man, a story as much about one person’s grief and desire to connect with another as about our species’ ambition and desire to conquer the final frontier.

The dawning realization, in What They Had, of why Robert Forster steps out of the bedroom he has shared with Blythe Danner for 60 years, sparing her more suffering and loving her until the end.

A deceptively simple scene—a conversation in a car going from one neighborhood to another—that’s a revelation of social inequality and how near yet far we live from each other. In minutes, Widows covers centuries of relationships of power.

An unexpected funeral in The Gospel of Eureka that breaks the audience’s heart and calls forth our loves.

And the titular character Christopher Robin, who holds Pooh Bear’s hand as they walk through a field, as though Terrence Malick is directing the film.

TWENTY YEARS AGO, when we talked about the “digital divide” we meant things like low-income people’s access to computers and the internet. But according to a recent study from Common Sense Media, that turn-of-the-century gap has largely closed. Seventy percent of families with an annual household income below $30,000 now have a computer at home, and 75 percent have high-speed internet access. In addition, low-income families are near the national average for access to mobile devices such as smart phones and tablets.

But another digital divide is emerging that could have more dangerous long-term consequences.

Researchers have discovered a lot about how brain development and personality formation happen, and their lessons keep coming back to the importance of real-world experiences and face-to-face human interactions, especially in the childhood years. To avoid passivity and mental laziness in their children, many high-income parents are starting to limit their children’s time on digital devices. Common Sense Media found that the children of upper-income families spent half as much time in front of screens as did children of low-income families.

Several private schools are even dialing back their reliance on digital technology. Meanwhile, in many public schools, students are being issued Chromebooks or iPads and shunted into online learning programs. According to Education Week, American schools spend $3 billion per year on digital content, as well as $8 billion-plus yearly on hardware and software, with little to show for it so far in the way of improved learning.

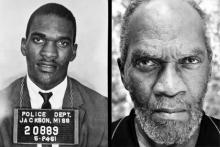

Freedom Ride

The expanded edition of Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders revisits a pivotal civil rights campaign. Filled with mugshots and recent interviews of several riders who were arrested in Jackson, Miss., Breach of Peace honors a historic act of protest. Vanderbilt University Press

One Body, Many Parts

Together at the Table: Diversity Without Division in the United Methodist Church, by Bishop Karen P. Oliveto, the UMC’s first openly LGBTQ bishop, is timely as the denomination nears a potential split over sexuality. Oliveto outlines how her denomination can remain whole. Westminster John Knox Press

IN THE SPAN OF OUR HOUR-LONG conversation, Mimi Mutesa, an emerging Ugandan-American photographer-videographer and an undergraduate student at Calvin College, a Christian Reformed school in Michigan, easily gives her thoughts on everything from the complexities of blackness to the policing of women’s bodies. However, when I ask her how her faith influences her work, there is a brief pause on the other end of the line.

“I don’t think it’s ever crossed my mind until this moment,” she says. When pressed, she explains that she’s “trying to tackle enough issues” in her art as it is, and evangelical culture has “far too many other problems” for her to address. Mutesa assures me that she still identifies as a person of faith but maintains that her relationship with God is “separate” from her relationship to art and social justice.

Perhaps this separation is a necessary one. It’s hard to imagine the average evangelical church embracing Mutesa’s colorful portraits of nude black joy. Her sentiments echo an unspoken opinion held by many young Christians, that if you want to be radical like Jesus was, you must do so on the margins of Christianity. More traditional folks may see this rush to the margins as a slick avoidance of the Christian call to profess one’s faith, or a symptom of postmodern discomfort with absolute truth. But what is more likely is that millennials of faith, especially millennials of color, want to engage with values traditionally cherished by the church but see modern-day Christianity as a direct hindrance to that sort of exploration, since significant portions of the church have been antagonists in struggles for social equality.

Reticence to conflate personal faith with artistic vision is deeply connected to a complex historical dialectic between the arts and the church: Mutesa’s midconversational pause is supported by precedent.

EVERY WEDNESDAY night, Sam’s youth group met in a darkened gymnasium dressed up as a rock concert: decorative fabrics, professional sound equipment, and a light show. A thin, attractive youth pastor with a soul patch and skinny jeans would deliver a message about the evils of sex, drugs, and alcohol.

In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus says, “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery.’ But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” This was a favorite verse of Sam’s youth pastors, who wielded it to warn kids against even thinking about sex. If lusting after a woman was just as bad as committing adultery, their logic held, then even thinking about sex is a sin.

“The weird thing,” Sam told me, “was that it wasn’t date rape or sexual harassment or even treating people disrespectfully that they were worried about. It was ‘impure thoughts’ and lust.”

There are two problems that I see here: One, these were teenagers, whose bodies are designed by God to become sexual, and two, the Greek word for lust, epithymia, is about general desire, not thinking sexual thoughts. If epithymia was a term for sexual desire, it would make some other things Jesus said super weird. (For example, Luke 22:15: “And he said to them, I have had sexual thoughts about eating this Passover with you before I suffer.”)

“Justice” was on people’s hearts, minds, and search histories this year. The word was named Merriam-Webster’s "Word of the Year" for 2018 after being consulted by users 74 percent more than in 2017.

WHEN I WAS a high school soccer and basketball player, locker rooms were a sanctuary for me. I remember elaborate pregame handshakes and earnest debates over whether it was okay to pray for a win. I chatted with teammates about defensive strategy, physics homework, and crushes. But I do not remember anyone ever bragging about sexual assault.

Donald Trump excused as “locker room talk” his vulgar boasting about kissing, groping, and trying to have sex with women during the infamous 2005 conversation caught live by Access Hollywood and released during the 2016 campaign. Trump’s lewd remarks still loom large for me, because I refuse to normalize having an admitted sexual assaulter in the Oval Office and also because UltraViolet, a creative women’s advocacy organization, periodically plays that videotape on a continuous loop in front of the U.S. Capitol. Tourists, members of Congress, and everyone else get a regular reminder of who is in the White House.

However, as UltraViolet’s action and the flood of #MeToo testimonials demonstrate, it is not enough to shine a light on the prevalence of sexual violence. Revelation alone does not beget liberation. We can’t simply hold up a mirror to our cultural misogyny and expect the image to change. For real transformation, we must project a true image—an imago dei —rather than our current distortion.

1. VIDEO: The Church That Meets in a Parking Lot

Every year thousands of churches shutter their doors and die. But here's one congregation that found that shutting their doors — and destroying their building — gave them a new way to survive. Watch and learn more about Los Angeles First United Methodist Church.

2. He Built an Empire, With Detained Migrant Children as the Bricks

The New York Times does a deep dive on the founder of Southwest Key Programs, which has collected $1.7 billion in government contracts and houses more children who have crossed the border than any other detention group in the nation.

Last week, the world was introduced to John Allen Chau, the U.S. American “adventurer” and missionary who was killed by an indigenous group on North Sentinel Island. According to a statement from missionary organization All Nations, Chau was a “seasoned traveler who was well-versed in cross-cultural issues” and had “previously taken part in missions projects in Iraq, Kurdistan and South Africa.” Now, Indian police have begun the dangerous mission of trying to recover the body even though a tribal rights group has urged officials to call off the search, claiming it puts them and the indigenous group in danger.