STORIES ARE more than mere entertainment: They rest at the heart of who we are. They shape our understanding of the world and how we choose to live in it, both individually and collectively. They can sever us from one another or call us into deeper communion. This is the message at the center of two new books by Gareth Higgins (a Sojourners columnist) and Brian D. McLaren (a Sojourners contributing editor).

In The Seventh Story: Us, Them, and the End of Violence, Higgins and McLaren suggest that the violence and division that is part of our past and present are neither inevitable nor coincidental. They’re part and parcel of the stories we live by. The authors highlight six story types that are particularly pernicious and all too common: stories of domination, revenge, escapist isolationism, scapegoating, acquisition, and victimization.

Drawing on what theologian Walter Wink calls “the myth of redemptive violence,” Higgins looks at the role these story types play in justifying and perpetuating violence. He reminds us that, as was the case in his native Ireland, it is the work of peace and reconciliation—not more violence—that is truly redemptive.

For his part, McLaren explores French anthropologist René Girard’s theories of violence. His discussion of Girard’s idea that desire and rivalry culminate in sacrifice and scapegoating provides an interesting lens through which to consider humanity’s tendency toward violence, as well as our current president’s willingness to demonize marginalized groups for political gain.

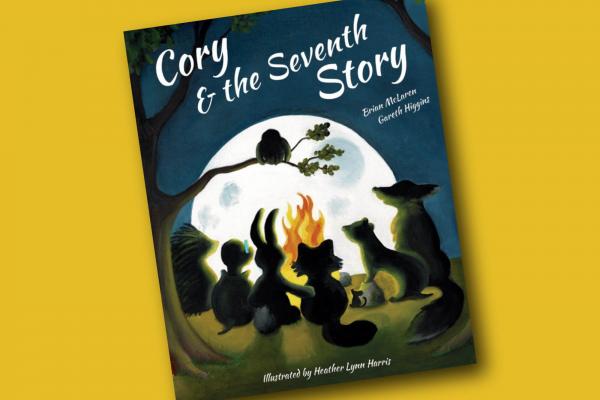

In Cory and the Seventh Story, the authors bring these outdated story types to life in an intriguing picture book for children. Centered on Cory, a story-loving raccoon, and the once idyllic Old Village in which he lives, the book opens with Badger attacking Fox and taking control of the Old Village. Neighbor soon turns against neighbor, and, as they do in our current political climate, division and anger rule the day.

Living in perpetual fear, the villagers rally their wagons into ever smaller circles. Some flee for greener pastures. Some plot to overthrow Badger’s despotic rule. Others project their fear onto their furless neighbors, blaming Frog and Lizard for all the village’s ills. When all these responses fail, the villagers turn even further inward, clinging to no more than the shiny objects they’ve acquired, hoping that their material gains will, if not save the village, at least provide some kind of individual salvation.

Just when Cory thinks all is lost, a stranger appears in the Old Village, offering a different story—the seventh story—and with it a way forward.

In Higgins and McLaren’s typology, seventh stories are unique. They suggest a way of reconciliation and love that acknowledges our fundamental interdependence. The authors are quick to point out that, for all their uniqueness, seventh stories are not new. The story of Jesus is a seventh story, as are the stories of all the great spiritual leaders who have shown us that there is no “us” and “them,” only “we.”

In a nation led by an avowed nationalist whose preferred symbol is a wall, stories of love and reconciliation are rarer and more essential than ever before. We must share them, savor them, and ultimately learn to live in their light.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!