Posts By This Author

Why I Stopped Watching ‘Brooklyn Nine-Nine’

“Crime shows are propaganda for the police, telling the American psyche that we need cops to maintain order.”

IN THE FIRST season of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, the show’s main protagonist, Jake Peralta (Andy Samberg), arrests a jewel thief named Dustin Whitman (Kid Cudi) without sufficient evidence, and the entire precinct spends the next 48 hours trying to fix his mistake. By showing the police detectives desperately trying to find evidence, Brooklyn Nine-Nine portrays the arrest as a puzzle to be solved instead of an abuse of power.

With likable characters and sharp writing that hits more than it misses, Brooklyn Nine-Nine has cemented itself as both a critic and crowd favorite, earning Emmy nominations and massive support from its networks, NBC and Fox. Its cast is one of the more diverse on television, and so are its characters. The police captain is a gay, Black, married man. Two of the other detectives are Latinx; one of them is a bisexual woman.

But at the end of the day, the show sanitizes police brutality and misconduct with humor. Police incompetence in Brooklyn Nine-Nine is portrayed as funny and showing a need for the character to develop; it doesn’t threaten someone’s safety like it does every day in real life.

Portrait of an Economy on Fire

‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ reminds us what it's like to be on the margins; we make our own way together.

THOSE ON THE margins live by a different economy. In the film Portrait of a Lady on Fire, the main characters live on the margins of a patriarchal society, and how they relate to one another shows creative care.

In the film, set in 18th-century France, a painter and her subject— a woman scheduled to marry a nobleman in Milan—fall in love. The painter Marianne is hired under the guise of being a walking companion to Héloïse, who, as a symbol of rejection of her forthcoming marriage, refused to sit for a previous portraitist.

After Marianne shows Héloïse a portrait of her she’s completed in secret, Héloïse criticizes it and agrees to sit for Marianne. During these few days of painting, Héloïse’s mother leaves, and the house and its economy rearranges.

Earlier in the film, the three women left in the house had strict roles and responsibilities. Héloïse went for walks, Marianne painted, and the maid Sophie served food. However, as love develops between Héloïse and Marianne, the household leaves behind the strict norms of aristocracy and assumes a much more egalitarian space. In a striking scene filled with role reversal, the lady Héloïse cooks, the artist Marianne pours wine, and the maid Sophie cross-stitches. On the margins of patriarchy, the strict delineations of class are thrown away, and the three share responsibility and care for one another.

Mary Magdalene Inspires Feminist Electronica

Singer FKA Twigs points us to the richness of mediating and upending our understanding of Mary Magdalene.

TWO WEEKS AFTER Kanye West released a gospel album with watered-down theology in October 2019, British singer-songwriter FKA Twigs dropped a marvelous piece of sparse electronica with a spiritual tenor. Twigs’ album is gospel in its theological significance. West’s record is not.

Titled Magdalene, the 32-year-old Twigs’ second album is a “revelation,” according to Pitchfork. Throughout the album, the dancer-turned-R&B-genre-bender finds strength in the story of Mary Magdalene. The record’s title track focuses on the Magdalene and the social implications of Jesus’ relationship with her.

Twigs frames the album as a feminist reconsideration of Mary’s story, pushing back on the fact that her narrative was ultimately told by male writers. Outside of Jesus’ family, she is the woman most mentioned in the gospels. She was a patron of Jesus’ ministry and among the first to have seen him resurrected. However, throughout much of history she has been conflated with the “sinful woman” in Luke 7 and, as a result, seen as sexually promiscuous. Twigs pushes against this patriarchal gaze and turns to the Magdalene for inspiration.

‘Parasite’ Highlights the Darkness of Wealth and Colonialism

In Bong Joon-ho’s breakout thriller, obsession with American consumerism and colonialism leads to great deception.

IN BONG JOON-HO'S Parasite, being upper class means loving Western culture—and its colonialism.

Spatial metaphor structures the award-winning dark comedy from the Korean director. Families and living spaces are the primary characters and settings for the film. The poor Kim family lives in a cramped basement apartment, and the rich Park family lives high up in the hills of Seoul.

(Warning: Spoilers)

In the first half of the movie, the Kims’ son Ki-woo is hired as an English tutor for the Parks’ daughter, and the Kims scheme to get each member of their family employed by the Parks. Their plot runs smoothly, and the Kims relax at the Parks’ luxurious home while they are away. But the movie’s clean narrative line drops when a third family and their living arrangement are revealed. The former housekeeper returns to expose a subterranean bomb shelter in the Parks’ home where her husband has been living, unbeknownst to the Parks.

The former housekeeper and her husband sit even lower in the class hierarchy than the Kims by living completely below ground.

Hollywood's Golden Age of Racism

How early cinema nativism led an Asian American actor to success—and how the church helped crash his career.

IN THE EARLY days of Hollywood, Japanese-born actor Sessue Hayakawa (1886-1973) was an icon. In the context of racist U.S. policy and increasing nativism in Hollywood, he was arguably the first non-Caucasian actor to gain international fame and the first person of Asian descent to become a leading man in the movie industry.

His overall career, however, is a story of race’s shadowy relationship with success. Orientalism, Yellow Peril, and America’s fear of Japan both helped and hurt his career. The Catholic Church’s eventual oversight of Hollywood also played a part in his troubles. The only way Hayakawa thrived in the industry was by playing into the structures of racism that set up his stardom.

“Such roles are not true ...”

IN 1915, WITH actress Fannie Ward, Hayakawa had the first on-screen interracial kiss.

Well before the Motion Picture Production Code outlawed interracial romance in 1930, the silent film The Cheat (1915) shows Edith Hardy (Ward) as a wife who takes money from the Red Cross, loses the $10,000, and then struggles to repay her debt. As she reels from the news of her loss in a semiconscious state, an acquaintance, Hishuru Tori (Hayakawa), assaults her and steals a kiss before she comes to her senses.

The silent film continues as Hardy describes her debt to Tori. Tori writes a check from his exorbitant wealth—he is described by title cards as a Japanese ivory trader—but not for free. He expects something from Ward.

When Hardy goes to repay Tori after her husband makes a hefty return on an investment, Tori locks the door and assaults her a second time. He brands Hardy with a circular seal; after she falls to the ground, the camera focuses on the stark black mark on her white shoulder.

The branding scene caused uproar in the Japanese American community. A Japanese newspaper in Los Angeles denounced Hayakawa, his sinister character, and the character’s appearance as a harmful stereotype. (Hayakawa reportedly had asked Cecil B. DeMille, the director of The Cheat, to change the clothing and mannerisms of his character, but DeMille disregarded him.) The backlash was enough for the film to be re-released in 1918 with Hayakawa’s character changed to a “Burmese king,” presumably because the studio believed Burmese people would have less volume to their voices of dissent.

“Such roles are not true to our Japanese nature ... They are false and give people a wrong idea of us,” said Hayakawa in 1916. “I wish to make a characterization which shall reveal us as we really are.”

Don't Tell Her

The emotions of “The Farewell” may be universal but the specific cultural scripts belong to each of us.

You may know 別告訴她 by its English title: The Farewell.

The second feature film from director Lulu Wang stirred audiences with a story from Wang’s family. In the film, the main character, Billi, joins her family in China as they convene a wedding as an excuse to say goodbye to her grandmother, who has a terminal illness but does not know it.

At the wedding, the grief of imminent loss peeks through the haphazard nuptials. In some of the film’s most memorable moments, toasts take heartrending turns into breakdown, and a drinking game provides space to drown sorrows with alcohol and laughter.

In the game, Billi’s family is seated at a round table. Chanting in Chinese, one person repeats a phrase while flapping their arms like wings, then looks to another person, who takes over the chant. Whoever makes a mistake takes a shot. The general mechanics of the scene are clear, but unlike most of the film, there are no English subtitles.

Singer Mitski Doesn't Owe Us Anything

Her performance is a powerful inversion of expectations for Asian women in America.

IN A SMALL VENUE, I watched Mitski perch on a white chair behind a white table, fold her hands, and start to sing emotional ballads.

The 29-year-old musician was performing in Carrboro, N.C., from her fifth studio album, Be the Cowboy. It’s one of my favorites from 2018 and plays with the American cowboy mythology in its loneliness (“My God, I’m so lonely ... still nobody wants me,”) and longing (“I just can’t be without you”).

I expected a typical concert, hearing favorite songs and seeing Mitski’s personality. But I was jarred by the lack of emotion she showed. The entire time she sang, her face was resolute and hardened, a seeming contradiction with her heartrending lyrics.

Second, she danced sensually, even while her face remained impassive. She wore nothing “sexy”—a white T-shirt, biker shorts, and kneepads—as she executed carefully choreographed sequences. But she leaned forward, slanted her hips, and flicked her hair. She climbed onto the table and spread her legs toward the audience. Yet she never broke a smile, never performed the emotion of eroticism.

Whiteness Determines Which Artworks Can Be ‘Masterpieces’

We've had enough ‘masters.’

WHEN I TRAVEL to a city, I find art museums and their masterpieces: “Sunflowers” in Amsterdam, the “Prodigal Son” in St. Petersburg, “David” in Florence. Van Gogh, Rembrandt, Michelangelo. These are masters, according to some cultural imagination.

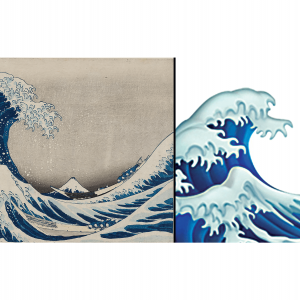

But it wasn’t until this past April that I encountered an Asian master and masterpiece: Katsushika Hokusai’s “Under the Wave Off Kanagawa.” The print is better known as “The Great Wave”—you know, the Apple wave emoji. Why is this the first Asian masterpiece that I’ve seen?

Respecting the Spirituality Behind Marie Kondo's 'Tidying Up'

Kondo focuses not on the aesthetic or the number of things; she instead focuses on the owner’s relationship to the object itself, whether or not it “sparks joy.” She advises, “Take each item in one’s hand and ask: ‘Does this spark joy?’ If it does, keep it. If not, dispose of it.” This relationship to objects is crucial to Kondo’s method and hinges on her Shinto background. Though KonMari is self-help, it’s self-help rooted in a Shinto spirituality.

Childish Gambino Offered Me Religious Experience, Not A Product

Donald Glover aka Childish Gambino has become a cultural icon. From his comedic work in Community to his acting in both Marvel and Star Wars franchises to his writing and producing of the critically acclaimed show Atlanta, the versatile Grammy-nominated artist is a creative force. Throughout all of this commercial and critical success, Donald Glover has refused to frame his work as a product; instead he wants to offer a participatory experience, a religious experience even.

Asian Representation Needs Both 'Crazy Rich Asians' and 'Sorry to Bother You'

The rift between rich and poor runs deeply through the Asian American and Pacific Islander community. A recent Pew study reveals that Asians, as a whole, “rank as the highest earning racial and ethnic group in the U.S.” But the top 10 percent of AAPI persons earn 10.7 times the amount of those in the bottom 10 percent.