IRISH POET Patrick Kavanagh famously said, “Any poet worth his salt is a theologian.”

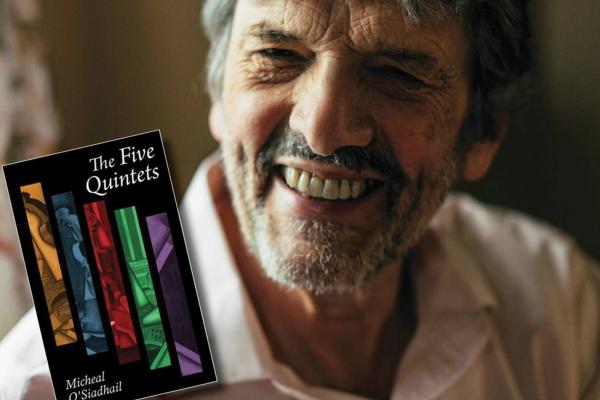

In The Five Quintets, a poetic tour de force by Micheal O’Siadhail, Kavanagh’s quip is flavorfully borne out. Quintets offers a sustained reflection on Western modernity (and its yet unnamed aftermath) in the vein of The Divine Comedy, Dante’s sustained reflection on medieval Europe (and its aftermath, the Renaissance).

O’Siadhail (pronounced O’Sheel) inspects 400 years of Anglo-Atlantic culture—artistic creativity, economics, politics, science, and “the search for meaning”—with the skillful hand of a citizen-poet, refracted through an Irish Catholic soul. Dublin born and educated, now poet in residence at Union Theological Seminary in New York, O’Siadhail embodies the vatic tradition of the Hibernian Gael—poet, prophet, priest, and, at times, jester.

His blind guide for the modern era is Madame Jazz—who encompasses klezmer from the Jewish shtetls and céilí music from famine Ireland as well. Jazz is the consummation of all that is truly human, the best of our polyphonic harmonies, a wild, joyful freedom born of shared suffering. Her chilling counterpoint, who ends the age of monarchs, is Madame Guillotine, whose shadow reaches forward into our War on Terror.

Read the Full Article