Arts & Culture

I FIRST BECAME aware of Tricia Hersey’s work through social media (@TheNapMinistry on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook), and I suspect many others have as well. Yet, Hersey is hardly your run-of-the-mill social media influencer and indeed can be brutally critical of the effects that social media culture has on our bodies and souls. Hersey is a performance artist, activist, theologian, and, perhaps most importantly, a daydreamer. Her work is centered on Black liberation, and particularly liberation from the present-day grind culture of capitalism that is driven largely by social media. In her first book, Rest Is Resistance, she aims to recover the divinity — that is, the image of God — in every human.

Rest Is Resistance is a stunning call to a slower, richer life of faith. Hersey’s writing seems animated by concerns such as those articulated by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel in his classic book The Sabbath. While humanity may live and work in a technological society, both writers argue, we do not have to be subservient to our technological tools. Our technological victories “have come to resemble defeats,” writes Heschel. “In spite of our triumphs,” he continues, “we have fallen victims to the work of our hands; it is as if the forces we had conquered have conquered us.”

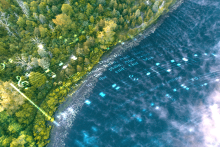

The Green New Dealings

To the End follows women of color as they advocate for the Green New Deal and face opposition within their political party. The documentary spotlights Sunrise Movement’s Varshini Prakash, Justice Democrats’ Alexandra Rojas, the Roosevelt Institute’s Rhiana Gunn-Wright, and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Jubilee Films

IN JULY, Lee Bennett Jr. stood at the podium of the Gaillard Center in downtown Charleston, S.C., as part of a three-day bicentenary commemoration of Denmark Vesey — a free Black man who had planned what could have been the largest organized resistance by enslaved people in U.S. history. Bennett brought both American history and personal history with him that day: The space where he spoke used to be his own neighborhood. There are some places where the veil between past and present feels especially thin.

The next day, Bennett offered me a tour of Mother Emanuel AME Church, where he is the historian. He spoke about Vesey, a founding member of Hampstead AME Church, established in 1818. In 1822, Vesey was arrested and executed, along with 34 others, for his plan to liberate the enslaved people of Charleston. Later that same year, a white mob destroyed Hampstead Church. By 1834, the city of Charleston made it illegal for Black congregations to meet, pushing the congregation to gather in secret until after the Civil War. In 1865, they came out of hiding and took the name Emanuel, “God with us.”

EMILY (AUBREY PLAZA) is caught in a vicious catch-22. She’s in deep student debt, but a criminal infraction keeps her from getting a job to pay down her balance. Emily’s stuck working catering gigs, and what little money she can set aside goes to her loan interest, practically ensuring she’ll never be able to get her head above water.

When a co-worker offers her a chance to make some extra cash, Emily jumps at the opportunity. It may be highly illegal, but what other choice does she have?

Writer/director John Patton Ford’s Emily the Criminal is a millennial version of classic gangster noir, with Plaza’s Emily drawn deeper into a criminal underworld where fast payout overrules ethics. Ford’s film never glamorizes Emily’s experiences, instead showing us a desperate person fed up with a world that gives her virtually no other choice but to break the law to survive.

THE PRIEST WALKS into the bedroom to face the little girl. It’s not a little girl, though. Something dark, something other looks out from her eyes. It opens her mouth to spew blasphemies, obscenities. The priest raises a crucifix, shouting, “The power of Christ compels you!”

So goes The Exorcist, the 1973 Oscar winner directed by William Friedkin. As a 17-year-old, I was not prepared for the visceral horror of seeing a possessed young Regan (Linda Blair) serve as the battleground between God and the devil. Neither were my Southern Baptist youth group friends who watched with me in my home. And neither were their parents, who (according to my long-suffering mother) were quite angry that I had hosted this viewing.

On the surface, those parents’ horror is understandable. The Exorcist more than earns its R rating, with gore and a good bit of blasphemy. But sit with Pazuzu (the demon) for a little longer, and it becomes clear that the film aligns well with conservative evangelical politics — a perspective in which I was raised and which persists in many corners of the U.S. church today.

Gutsy introduces us to dozens of trailblazing women who are living lives of justice, truth, love, leadership, humor, and reconciliation. The show, produced and hosted by Hillary and her daughter Chelsea Clinton, while not explicitly “faith-based,” is rich with examples of women cultivating the common good. In a recent interview, Chelsea Clinton told me that there are as many ways to be gutsy “as there are women in all of our lives.”

Because being Catholic was not the norm in my community, I was often teased about our non-contemporary music and the liturgy, and I was accused of worshiping Mary. Mostly, I was told over and over again that I wasn’t a Christian. The latter happened all the way through college. I was so boggled by this because I knew I had what the Baptists liked to call a personal relationship with God. Yet I was told by children and adults alike that it wasn’t valid if it didn’t fit their formula.

Mary Oliver often explored big existential questions with the unlikeliest of philosophical partners: moss, roses, geese, dogs, waves. They all had interesting things to say to her. In a 2015 interview with Krista Tippett, Oliver explained that there is nothing more interesting to her than spirituality. “So I cling to it,” she said. “I have no answers, but have some suggestions.” Her poems are riddled with those suggestions. Here are some of my favorites

The stories we tell ourselves matter, even if you’re an immortal elf. The first season of Rings of Power, Amazon Studios’ new 8-episode prequel to The Lord of the Rings, opens with the scene of a young Galadriel, the Elvish royalty who will refuse Frodo’s offer to wield the One Ring thousands of years in the future.

As it turns out, the person who needed The Rehearsal most was Fielder himself. His interaction with Angela in the finale reveals that the whole enterprise is actually an exploration of the inevitable pain humans cause others, even when we’re not trying to, and our need for grace and self-forgiveness.

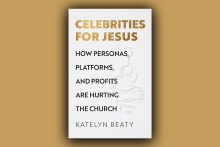

The outrages of celebrity culture have a material basis, with flashy sneakers and luxurious living, but Beaty’s analysis expands to include a deeper psychological and spiritual perspective on the problem.

Viewers would be wise to approach The Sandman expecting a slow burn rather than a breakneck action extravaganza. There’s plenty of horror, but these moments are spaced out through the deeply human moments of Morpheus coming to terms with what it means to serve humanity.

I went to the theater alone, feeling small and bereft. At the urging of a friend, I went to see Marcel the Shell With Shoes On. I felt my smallness increase as the theater darkened. Then suddenly, there was Marcel, a one-inch-tall shell, blinking back at me. Marcel is soft-spoken, inquisitive, and wears pink shoes.

The June release of a Climate Vigil The Porter’s Gate Worship Project aims to nudge Christians toward climate action, but it isn’t alone among contenders to inspire the climate movement. For over 20 years, Carolyn Winfrey Gillette, a Presbyterian minister from New York, has written hymns for the times, including one for the 2021 UN climate talks held in Scotland and several to recognize increasing natural disasters such as wildfires, hurricanes, and floods. Fossil Free PCUSA, a campaign within the Presbyterian Church (USA) has used hymns in protests, including songs by Christian artist Matthew Black.

All I wanted was work,

not the old man’s joyful tears as he ran down the hill.

I was afraid he’d fall or burst his heart to kingdom come.

Now what?

My head still pounds from yesterday’s wine, father’s ring hangs heavy on my finger,

and after all those years of pea pods, my stomach aches from too much fatted calf.

I didn’t want that damn banquet,

my older brother pacing outside the door, muttering into his beard.

But he’s right: he deserves a party more than I do.

And next?

THE RINGS ARE BACK. In September, Amazon Prime Video premieres The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, the newest adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth legendarium. From The Hobbit toThe Lord of the Rings trilogy to The Silmarillion, Tolkien is one of the most beloved fantasy authors of all time. His fictional world has captivated generations of readers and inspired countless spin-offs.

The newest series takes place during the Second Age, long before The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. It includes some characters portrayed onscreen before and many more not. While a compressed timeline means story changes are expected, fans hope the show retains the essence of Tolkien’s truths rooted in his Roman Catholic worldview. In his essay “On Fairy-Stories,” Tolkien refers to the act of creating fictional stories as “sub-creation.” He writes that humans take pieces of God’s creation and use them to sub-create “because we are made ... in the image and likeness of a Maker.” Because sub-creation is an expression of God’s creativity, Tolkien also believed that fictional stories reflect truth.

Tom Emanuel, a United Church of Christ minister and Tolkien scholar, compares the resilience of Tolkien’s work to that of the Bible. “Why has the Bible continued to resonate for all these centuries? Because it offers us a glimpse of a Truth beyond everyday failures and disappointments, possibility beyond the worst we can do to one another,” Emanuel told Sojourners. Tolkien’s writings reflect the truth of a world in need of healing yet never without hope, a vision that resonates for Christians pursuing social justice.

AT THE START of the war in Ukraine, images overwhelmed me. Families crowding onto trains. Teachers holding assault weapons. Nigerian students being held at the border. The clash of human tenderness with extraordinary aggression was arresting. In between checking updates from a friend—an art curator sheltering in Kyiv—Instagram suggested I follow Lviv-based contemporary icon artist Ivanka Demchuk. With fears of global annihilation humming in my head, Demchuk’s fresh, calming pieces, such as “Annunciation” and “Sophia the Wisdom of God,” captivated my attention and softened the edges of my growing despair.

In recent years, Lviv has become a hub of Christian sacred art technique and production. Lviv National Academy of Arts, from which Demchuk graduated, teaches icon creation, sacred space decoration, and icon theology. For centuries, icons helped make Christianity accessible to illiterate populations. But today, it strikes me that we need this life-giving artform in new ways. We are inundated with photographs of violence, from destruction in Ukraine to police brutality in our neighborhoods. Jesus Christ, our Wounded Healer, taught his disciples how to see injustice and move toward it. How can we, as Christian people committed to justice, cultivate these twinned capacities—seeing clearly and seeking social healing—within ourselves?

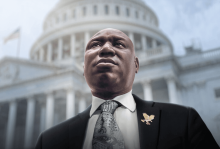

Legal Action

The documentary Civil: Ben Crump follows the civil rights attorney as he represents the families of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Andre Hill. While Crump’s work sheds light on police brutality, he also takes legal action to protect Black farmers and bank customers. Netflix

IT'S CLICHÉ AT this point to call television dramas with rich storytelling and emotional depth (think The Wire and Breaking Bad) novelistic. But no show may be more novelistic than Pachinko on Apple TV+. Like the book by Min Jin Lee on which it is based, Pachinko encompasses four generations of a Korean family, following them from Korea to Japan throughout much of the 20th century. But while the book moves linearly, the TV show shifts back and forth from 1989 to the 1920s onward, with one actor (Minha Kim) playing the protagonist Sunja when she is a young woman and another (Oscar-winner Yuh-Jung Youn from Minari) when she is a grandmother.

Hollywood often seems to assume that viewers need stories that match our limited comprehension. But lately there’s been a shift, with Korean artistry initiating the move. Hollywood, uncharacteristically, embraced the South Korean thriller Parasite, the first non-English-language film to win Best Picture at the Oscars, and went equally wild for the South Korean TV drama Squid Game, the first non-English-language show nominated for Screen Actors Guild Awards (winning three). Subtitles—kisses of obscurity in Hollywood—become something sweeter: Trust? If so, Pachinko puts double the faith in non-Korean- and non-Japanese-speaking viewers, subtitling the Korean in yellow and the Japanese in blue and juxtaposing the colors when both languages flow from a character's mouth in a single line of dialogue. At times, the bottom of the screen resembles Vincent van Gogh’s “The Starry Night.”

IN THE DARKNESS, I heard a voice calling my name: “Hi, Olivia.” I couldn’t control my arms and legs enough to acknowledge the voice. Again: “Hi, Olivia.” At this point I was feeling sheepish. Finally, the voice said to me, “Olivia, I think you’re muted. If you want, you can turn your mic on.”

The voice was that of Steven Roberts, who serves as Life.Church’s online host team pastor. I was attending my first church service in the metaverse.

The darkness faded, and I saw the words “Life.Church” written on the face of a computer-simulated grey, black, and white building. I (or rather my avatar) walked through the building doors into a lobby with welcome signs and informational graphics about the mission and history of Life.Church. There was even a game room with a playable pool table and dartboard. I directed my avatar to the sanctuary.

Life.Church is a multicampus church in the Evangelical Covenant Church denomination. Led by Craig Groeschel and based in Edmond, Okla., it has 44 physical locations in the U.S. and has now ventured into the metaverse.