Arts & Culture

Copaganda refers to any piece of media that portrays police as a necessary social institution. While this can include viral videos of police chatting with neighborhood kids or doing lip-sync battles, the most pervasive examples of copaganda are found in pop culture.

Proximity and humility are sometimes an answer for our beliefs.

The Bulgarian town where director Ivaylo Hristov’s latest film takes place is never named, but the movie’s title offers a suitable stand-in: Fear. This coastal village on Turkey’s border reeks of terror, but not the kind one might expect.

Reprinted by permission of Schocken Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg. Purchase the book at penguinrandomhouse.com.

IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE first commandment (“I am the Lord your God who has brought you out of the land of Egypt, from the house of slaves”) comes the second commandment—almost as though after a colon: “You shall have no other gods in My presence.” The Exodus represents a break for freedom, and the construction of a new identity based on that freedom. An important aspect of freedom is the separation not just from Egypt but from the fascination with Egypt’s gods. The Exodus is an iconoclastic project; entering a covenant with the One God is an attempt to break the idolatrous spell.

Eric Santner offers a psychoanalytic understanding of what he calls Egyptomania.

Date: Sunday, May 17, 2122

To: allchurch @gracechurch.metaverse

From: staff @gracechurch.metaverse

Subject: Children singing in church

RECENTLY OUR STAFF has received many questions about why we do not permit children to sing during services. We understand that this is a contentious issue, and we want to do our best to respond to these concerns. Before we begin, it must be made clear that on all matters of doctrine, we look to the sacred All-Church PDF sent out by our founding elders in the year 2022, almost 100 years ago, which clearly defined our church policy.

To begin, let us look at section 4.A of the holy PDF. It states: “Please do not allow your children to sing during the sermon, especially if it’s a shouted rendition of ‘We Don’t Talk About Bruno.’” Given this language from the foundational All-Church PDF, the prescribed ban on singing seems clear (although we’re not quite sure who Bruno was or why people weren’t supposed to talk about him). Some of you have noted that this directive may have been a response to disruptions during services. While it is true that we have found several cellphone videos from 2022 of children standing up to loudly sing in the middle of the Eucharist, there is simply no way to know if section 4.A of the PDF was written in response to that.

Touch me and see, because a ghost does not

have flesh and bones as you can see I have.

—Luke 24:39

So easily startled by vastness, dark

distances, arrival, they were terrified by him

that night glimmering in their midst.

Jesus knew they needed to finger the familiar

relief of bones under warm flesh to believe

the body, pale star

studding their peripheral vision, a specter

rattling even Peter, who had seen the not-

ghost of him before, walking the sea. Jesus

knew their need to know he hungered, tasted

the tilapia baked in olive oil with salt, lemon,

tangy fingers to mouth.

SOME CHURCHES HAVE fought to be exempted from the Americans with Disabilities Act, have interpreted scripture in ways that cause violence against disabled people, and are often rife with ableist microaggressions unique to religious communities. Amy Kenny’s My Body Is Not a Prayer Request—part memoir and part disability justice hermeneutic—is a book the church desperately needs.

Kenny encounters strangers, many of them Christians, who comment on her body. They describe their ableist version of heaven, pray over her without consent (she refers to these people as “prayerful perpetrators”), ask for personal medical information, and give pitying glances. “I wish I was whole in their minds,” writes Kenny, “enough to exist without needing a prayerful remedy to cast out my ‘demons,’ a full human who has something to offer other than a miraculous narrative.”

“WHO ARE THESE young people?” I asked repeatedly while reading Talitha Amadea Aho’s debut book, In Deep Waters: Spiritual Care for Young People in a Climate Crisis. The Presbyterian pastor writes of her adventures shepherding the youth of her Oakland, Calif., church through beach trash pickups, worsening fire seasons, the pandemic, and mundane youth group activities that lead to big conversations on God’s involvement and human response amid climate emergency.

Aho recounts driving a van full of youth near the 2018 wildfire that destroyed Paradise, Calif., to get to a retreat. “Whatever, we can deal with it. Breathing isn’t the only thing in life,” says one youth. Another, like a prophet, observes, “The Earth will survive; it’s a living organism, and we are the infection on it, and the Earth is cooking up a fever to kill us off.”

It may be that these West Coast youth are more clear-eyed in their diagnoses, living through an apocalyptic reality that we are all careening toward. I can imagine having similar talks with my own children, ages 3 through 8, in a few years. Already, my 8-year-old has said about climate change, “It’s too late.”

Creative Action

Capturing the vibrant 2019 protests that pushed Puerto Rico’s governor to resign, the documentary Landfall examines life after Hurricane María and the debt and environmental crises that devastated the U.S. colony long before, prompting local resistance and creative action. Blackscrackle Films.

WHEN I THINK about the 2015 HBO miniseries Show Me a Hero, the person who first comes to mind is Nick Wasicsko. This is understandable: According to its HBO blurb, the politician is the show’s main protagonist. But this scripted drama is about the real-life 1980s and ’90s struggle for public housing in Yonkers, N.Y., when low-income people of color worked for integration and the city government resisted—even as daily contempt-of-court fines threatened to bankrupt it. So, it feels weird to focus on the white Mayor Wasicsko, although he (eventually) fights for the public housing too.

This discomfort may be the point. “The thing I don’t buy anymore,” said the show’s co-writer, David Simon (The Wire, Treme), “is if we elect the right guy, the great men of history, that’ll save us. ... Our problems are systemic, and we’re going to have to solve them as people.”

I WROTE MY first “Eyes and Ears” column in January 1987 when I was a Sojourners staff editor. Over the ensuing years, I’ve changed from Protestant to Catholic, from full-time journalist to full-time teacher, and from city mouse to country mouse. I’ve been married to Polly Duncan Collum and helped raise four children. Through all that, I’ve kept this column going, but now I’m pulling the plug to make way for whatever’s next.

In my first column, I set out a twofold purpose for this space. I intended to track the merger of politics and popular culture that began in earnest with the 1980 election of a movie star president. I noted then that our public life was largely being reduced to an “ephemeral community of shared media experience,” by which, at the time, I meant mostly Hollywood movies and various televised spectacles.

By the time we elected a reality TV star as president, the convergence of politics and popular culture was already long complete, except that, in a world of microtargeted messaging, there is no longer even much “shared media experience” from which to forge a community.

My second rationale for starting the column, however, has held up a little better. I noted way back then that, in both politics and popular culture and in the intellectual netherworld of think tanks and commentary journalism, the very definitions of terms such as “America,” “democracy,” and “Christianity” were up for grabs. In 1987, I called this a “war of ideas” and it continues with a vengeance, though often degenerating into an emotional war of identities.

However, “stuff happens.” And in these 35 years, two big things have happened that exploded many of my expectations and drastically altered the cultural landscape.

Using theologically diverse Christian figures ranging from Billy Graham to Mister Rogers, Mayfield offers examples of what insecure attachment to God can look or feel like, including feelings of doubt, shame, or distancing. Leaning heavily on attachment theory — a theory that examines relationships and the nature of the bonds between people, especially between caregivers and children, romantic partners, and close platonic relationships — Mayfield provides a relatable guide to assist folks with identifying the deeper questions and beliefs behind some of our spiritual frameworks.

This spring, I’m thinking about the season as a blooming period for the complexities of truth. That’s not to say that truth itself is complicated, but that the application, acknowledgment, or apprehension of truth can be a sticky mess. Truth will set you free, but then we get to wrestle with freedom and the responsibility that comes with it: Realizing that racism is ingrained in the church is important, for instance, but acting to rid the church of that sin is paramount.

Lent is the angstiest season of the liturgical calendar: Jesus in the desert with the devil; us sitting with our sin and mortality. So below you’ll find six songs to accompany you this brooding, contemplative season. Soon, Easter will roll around and bring with it upbeat resurrection bops, but for now, the tunes are appropriately emo — at least lyrically.

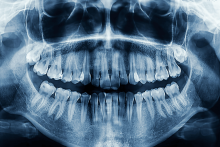

Several days ago, I spent more than I would have liked on a dental procedure that involved removing decay from one of my molars, doing a lot of horrible-sounding drilling and scraping, then saving the delicate bits that remained by capping it with a fake tooth. My dentist insisted this was called a “crown,” but I know a euphemism when I see one.

Last year, Suzanne Brennan Firstenberg, a social practice artist, created In America: Remember — a vast field of flags on the national mall, one for each American who died from COVID-19. Visitors, both in-person and digitally, had the opportunity to dedicate a flag by writing a message on the while poly film. When the installation began in mid-September of 2021, there were 666,624 deaths. When the installation closed in early October, there were 701,133 deaths. As of this week, nearly 1 million people have died of COVID-19 in the United States, 6 million globally. As we try to grapple with the weight of these fatalities, we’re revisiting an interview from late October 2021 between Firstenberg and Sojourners associate culture editor Jenna Barnett, in which they discuss what it looks like to honor grief and memorialize an ongoing pandemic.

When I was a kid, Christian comic Brad Stine yelled at me about wearing a helmet while riding my bike. He also yelled about seatbelt and car-seat laws, smoking laws, and gay marriage through his stand-up routine that I sat in the front row for.

This is a tale of two orphans, Bruce and Jephthah. A tale of two cities, Gotham and Gilead. A story of curses and vengeance and redemption.

My father saw Lent as a chance to build a more sustainable life, much like training for a championship game. As a mother and teacher of environmental education in the mountains of North Carolina, I couldn’t have imagined how the Lenten practice of my childhood would help me face both life and death amid a global climate crisis decades later.

ALLOW ME TO introduce myself: I’m IKEA, an expert in DIY construction and deconstruction, here to explain a recent religious phenomenon. According to a 2021 Relevant magazine article, Christianity is in “the age of deconstruction.” “Through deconstruction,” explains writer Kurtis Vanderpool, “we are able to find the good and the helpful parts of our faith upbringing, while reshaping or throwing out the unhelpful.” But there is a problem! While the exvangelicals on Twitter are obsessed with deconstruction, “most people you will find in church are uncomfortable with deconstruction,” says Vanderpool.

You may be thinking, “Is an enormous warehouse full of good-enough furniture really equipped to explain a sensitive theological process? No offense, IKEA, but did you even go to seminary?” No, I didn’t. But nondenominational churches often pay me thousands of dollars to host massive lock-ins and I overhear A LOT of really bad theology as youth pastors, groggy chaperones, and sugar-faced youth groups play hide-and-seek in my showrooms. (I’m pretty sure I didn’t dream this.)