Arts & Culture

My stanzas do not resemble marimbas

after all. These lines are the warmed

rank of organ pipes, droning & melting

their millennia into my shoulders.

Yes, yes, my God is heavyset & broad

& not a week of childhood passes

without Bach or Luther or a collect

that echoes the grungy psalmist

Used with permission from Orbis Books (orbisbooks.com)

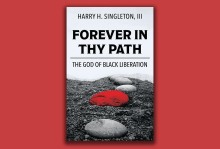

TO ITS CREDIT, the Black church seeks to instill a sense of “somebodyness” through positive reinforcement in conversion. But it seeks to do so without deeply immersing the convert in the true history of his/her culture. Consequently, the Black church falls prey to the universalism of the white church by naïvely thinking that one can be a true child of God while possessed of a deformed racial self-image. In so doing, the static conservatism of the Black church is at odds with freedom movements and prophetic leaders who are able to judge rightly that the freedom of Blacks cannot come through a rejection of one’s history, whether intentional or not.

IN OCEAN VUONG'S latest collection Time Is a Mother, the T.S. Eliot Prize-winning poet reaches for depths of what was lost.

We encounter Vuong submerged in profound and compounding grief after the death of his mother. The book’s epigraph from César Vallejo reads, “Forgive me, Lord: I’ve died so little,” touching on the guilt that can accompany those left behind after a death. These poems hold the tension between looking back and moving forward, with the awareness of someone acquainted with feelings “that made death so large it was indistinguishable / from air,” as Vuong writes in “Not Even.” Those grieving search for comfort, while also examining life before loss—sometimes recognizing that grief was always present.

Time Is a Mother is full of questions that reckon with these past experiences. One of the first poems asks, “How else do we return to ourselves but to fold / The page so it points to the good part.” Other verses ask, “What if it wasn’t the crash that made us, but the debris?” and “How come the past tense is always longer?”

WHEN I PICKED up Get Untamed—a journal based on Glennon Doyle’s best-selling memoir Untamed—at a secondhand bookstore, I was, as the kids say, down bad. Real bad. A year of overscheduling, overcommitting, and underhydrating had turned me into the caretaker of a creative and existential abyss. In that bookstore, I was reaching for more than a how-to book. I was reaching for a lifeline. And I found one—just not in the way I expected.

Doyle emerged onto the nonfiction scene with Carry On, Warrior in 2013, followed by Love Warrior in 2016. The latter book was raw and vulnerable, detailing the dissolution and resurrection of Doyle’s first marriage. Acclaimed by Oprah, Brené Brown, and Elizabeth Gilbert, Love Warrior celebrated love’s ability to overcome all obstacles—from addiction to internalized misogyny—in a marriage. Then Doyle met retired professional soccer player Abby Wambach. Doyle and her husband divorced. Now Doyle and Wambach are, by all accounts, happily married. The events leading to this form the basis for Untamed.

IN A 2001 lecture titled “Devotional Cinema,” filmmaker and film editor Nathaniel Dorsky broadly described devotional practice as “the interruption that allows us to experience what is hidden and to accept with our hearts our given situation.” Dorsky connected this definition to the experience of watching a movie, claiming, “It is alive as a devotional form,” allowing viewers to uncover truths about themselves and the world by watching someone else’s story. A movie doesn’t have to be experimental art, a heavy drama, or a religious epic to be a devotional experience. Often, the most profound stories are about the subtle changes of the soul over time and the experiences and relationships that define a person. We relate to them because, like a devotional practice, they help us reflect on our own lives and consider how we live in relation to others.

Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World is one such film, following its protagonist, Julie (Renate Reinsve), from her late 20s to her early 30s. Trier places Julie as the main character of her own story, narrated to us as she lives it, changing careers, falling in love, breaking up, experiencing loss, and becoming wiser and more comfortable with herself as a result.

WHEN I FIRST read Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem “truth” early last year, I did a double take to make sure it wasn’t written in 2021. The 1987 poem personifies its titular subject as a living being that can knock its “firm knuckles / Hard on the door,” whose arrival brings an equal mix of anticipation and apprehension. Brooks describes multiple responses one can have to the arrival of truth. For those who have made peace with lies, the truth can be threatening: “Shall we not dread him, / Shall we not fear him / After so lengthy a / Session with shade?” Even for those who have longed for truth’s arrival, blissful or willful ignorance seems to be a better alternative than the terror of having to engage truth head on: “Shall we not shudder?— / Shall we not flee / Into the shelter, the dear thick shelter / Of the familiar / Propitious haze?” Regardless, Brooks makes one thing clear: The question is not a matter of if truth will come, but when. The most important question of our lives then becomes, how are we to greet it?

In the poem, Brooks doesn’t name the truth that haunts her—although since she first published it in 1949, as the stage for the civil rights movement was being set, one possibility might be the systemic mistreatment of Black people and white people’s willful obliviousness to it. I found the poem to be a peculiar comfort in this time as we try to adjust to an ever-shifting landscape of new realities and reckon with truths about ourselves we might otherwise prefer remain hidden.

Similarly, several films offer insight into how people receive truth’s advent.

Horror has always leaned on religion to provide the backbone for its explorations of evil, even before the first time Dracula cowered in fear at the sight of a cross. But religion doesn’t just inspire the horror genre, it utilizes it, too. The Bible is full of horror.

Moved by Love

The limited ABC series Women of the Movement follows Mamie Till-Mobley as she grieves the murder of her son Emmett Till and fights for justice. Directed by four Black women, the show tells the true story of the woman who helped fuel the civil rights movement. Two Drifters

“We want to recognize how you have blessed Bandit and how Bandit has blessed you.”

We are currently in the midst of what the American Library Association condemned in November as “a dramatic uptick” in efforts to challenge or remove certain books from libraries and schools. Many of these censorship efforts have been led by conservative Christians and conservative politicians who are concerned these books will dissuade their kids from embracing what they call “Judeo-Christian values.” But as Ryan Duncan explained, Christians are deluding themselves if they believe banning stories about gender, race, or sex will halt their kids’ curiosity. Ban ’em or burn ’em, these books will not disappear and kids will continue to seek out resources on these topics — to some parents’ chagrin.

Maybe you’ve seen the now-viral clip: As air raid sirens wailed, a camera panned the skyline of Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital. The previous evening, Russia launched a full invasion of the independent democracy, prompting tens of thousands of Ukrainians to flee their homes. In the distance, the gold onion domes of a church glowed, architectural symbolism for divine light, intended to point worshippers to the world beyond. Then CNN’s coverage abruptly cut to an Applebee’s commercial.

Lincoln’s Dilemma, released this month on Apple TV+, presents a complicated version of the 16th president. The four-part series portrays Lincoln as a man of his time and place, wrestling with the culture war of his day: slavery.

Today is a day for magical thinking. The date — 2/22/22 — is a palindrome: Whether you read it forward or backward, the date is identical. Because the day also falls on a Tuesday, particularly enthusiastic followers of palindrome dates have been calling today “Twosday.”

If we analyze our current conditions, avoid circular debates, stop waiting for heroes to save us, speak honestly about our past and present, and try to change today, we might just save tomorrow.

Looking at Kanye West can be both difficult and easy. Easy because of his genius: how he put Chicago on the map as a hub for brilliant rap music, widened the lane for non-gangster rappers, and somehow made tunes seriously considering Jesus so sonically innovative and catchy that some become radio staples, paving the path for Kendrick Lamar and Chance the Rapper. Difficult because of his public antics: the outbursts, the flamboyance, the drama. Recently Kanye’s displays have even become dangerous, harassing his wife Kim Kardashian, who has filed for divorce, and threatening her rumored boyfriend Pete Davidson.

One of the defining features of cosmopolitan Protestantism is the sweet little promise — whispered even — that Christianity is not going to ruin your life. You can still love salty language (and I do) and feel justified by holding prevailing opinions (which I do) and have many mild to moderate faults that are not polite for me to mention. Its wonderful accommodation to modernity has liberated the church from a great many sins (Phariseeism, disembodied love, political acquiescence, etc.), but I’m afraid it has laid itself quite open to the glories of idolatry. And let me be clear, idolatry — which is to say, comforting false images of a true God — is the most fun in town.

I began to watch the show due to my love of sci-fi but the reason I finished all 218 episodes and remained faithful even throughout the 2016 reboot is because of Dana Scully. There’s not a more complex TV character than Scully: She is a medical doctor who knows karate and although she openly antagonizes her partner, Mulder, for placing stock in supernatural explanations instead of logical ones, she openly identifies as Catholic. Scully’s complexity gets to the heart of what the show is all about: the desire to believe.

Danny McBride’s HBO show The Righteous Gemstones is a dark comedy about corrupt, hyper-wealthy Christian pastors. The Gemstone family runs a famously successful megachurch in South Carolina, but behind the scenes, they evade taxes, snort cocaine, pull knives on their friends, bicker like filthy-mouthed children, and say things like, “You are forgiven for my suspicions of you.” And though they all live in mansions on the same compound, patriarch Eli Gemstone and his three adult children — Jesse, Judy, and Kelvin — generally only come together in spirit when they need to ward off blackmailers, snoops, and evil grifters from their past: anyone who might reveal their secrets or jeopardize the family’s wealth-hoarding.

It’s certainly ironic, but as much as the news can get me down it can also lift me up. Yes, legislators are attempting to censor books that teach about racial (in)justice and human sexuality — Weeble down. But these lawmakers’ attempts to censor theories are only resulting in increased interest and open-mindedness among their constituents — Weeble up!

the vast

and all its definitions had dumbfounded. I bit the hand

that fed imagination, took

for pestilence, the flies. For end-of-world, the gully washers.

I shook in handfuls

petals fetched from

doubt