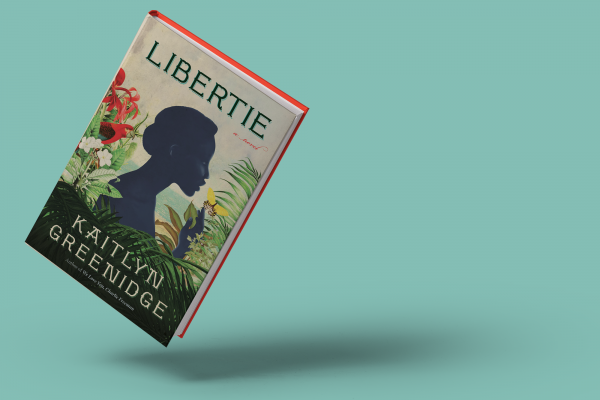

WHAT IS FREEDOM, really? When we first meet the titular narrator of Kaitlyn Greenidge’s novel Libertie, the year is 1860 and Libertie Sampson is a child in Kings County, New York, witnessing a miracle: Her mother, Dr. Sampson, raises a man escaping slavery “from the dead.” Her father, a former slave who died before her birth, named Libertie after his “longing” for “the bright, shining future he was sure was coming.” Libertie grows up watching her mother work, learning about the body’s ailments alongside the plants and remedies that can allay suffering. Perhaps this—the ability to heal, to gain access to a position other Black women could not, to guide others to life outside slavery—is the freedom Dr. Sampson envisions for her daughter, who is raised to follow in her mother’s footsteps.

But Libertie soon learns that she and her mother do not have the same privileges: Where her mother’s light skin allowed her access to medical school, Libertie’s dark skin means she cannot enter the same rooms as her mother. When white patients recoil from Libertie’s touch—and her mother does not defend or shield her—Libertie begins to lose faith in her mother’s version of freedom.

Read the Full Article