Sarah James, a biracial Indian American woman of color, is a graduate of Yale Divinity School and founder of Clerestory Magazine.

Posts By This Author

Learning To See Through Margaret Renkl and Mary Oliver’s Eyes

Painted Prayers

How sacred art from centuries ago reminds me of God’s loving presence today.

UPON READING THE news that the U.S. deported hundreds of migrants to El Salvador, I felt ill. Neri José Alvarado Borges had studied psychology and worked in a bakery. Luis Carlos José Marcano Silva is a barber with the face of Jesus tattooed on his stomach. As the daughter of an immigrant, I wept, thinking of their fear and families’ grief. In the face of a government that thrives on cruelty, we need resources that help us preserve our human capacities for hope, courage, and compassion.

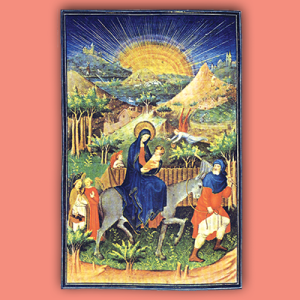

Recently, I’ve found comfort in paintings from books of hours, a form of prayer book popularized in Europe in the 1200s to make contemplation simpler for the laity. These paintings, known as “illuminations,” are distinctive and, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Wendy Alpern Stein, include “some of the greatest paintings and drawings of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance.”

Once the most published texts of their time, books of hours were often bespoke, commissioned by monarchs and aristocrats and crafted by luminary artists of the day. Each unique book of hours contains a liturgical calendar, gospel excerpts and psalms, and “The Hours of the Virgin,” which Stein calls “the heart” of the form, “a series of prayers and praise for the Virgin Mary [recited] at the eight canonical hours.” The books were made and written by hand. The illuminations include beautiful borders, often of botanical elements like ivy or flowers that decorate the edges of each page. Passages of text begin with an ornately decorated and framed capital letter. And the illustrations that complement the prayers and readings are drawn with vibrant colors and metals like gold and silver.

Mary Cassatt’s Tender Activism

Cassatt’s paintings remind me of the kind of person I want to be.

THE DAY AFTER the presidential inauguration in January, Episcopal Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, preaching at a prayer service for unity attended by President Donald J. Trump, warned members of the new administration that contempt is “a dangerous way to lead a country.” She pleaded for their mercy and compassion for the most vulnerable and outlined a vision for social healing founded on genuine “care for one another.” Budde’s words stand in stark contrast to the campaign of dehumanization and destruction we’ve witnessed since.

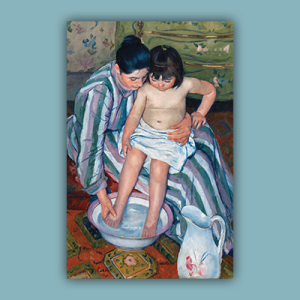

In the last few months, I’ve contemplated how, with incredible grace, Budde spoke truth to the power sitting before her in the pews. Her sermon left me feeling calm and convicted and brought to mind one of my favorite artists, the 19th-century impressionist Mary Cassatt. Like Budde’s sermon, Cassatt’s paintings are striking in their softness; they remind me of the kind of activist and person I want to be. I want to live with my heart softened and meet suffering with tenderness.

As Ruth E. Iskin explains in Mary Cassatt Between Paris and New York, Cassatt was “neither simply or completely a bourgeois, nor fully a precursor to the 1890s New Woman, but a mixture of both.” She was “anchored in a transatlantic network that included numerous conservative Americans” and an independent working woman who passionately supported women’s suffrage and full emancipation. In a male-dominated art scene, Cassatt made a name for herself with humanizing portraits of women of all ages, showing the relationship between caregivers and children and the dignity of motherhood. Her layered, emotionally vulnerable pieces highlighted the strength of women and the beauty and seriousness of care itself.

Her politics were characterized by a similar sensitivity. Iskin explains, “[Suffragists] claimed that the very role of mothers in the private sphere justified extending their activity into the public sphere of politics and government.” In other words, they made the case that the qualities of love, strength, and commitment exhibited by many women in their homes would also benefit civic spaces.

Imagining a Humane World

How Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetry helps me dream again.

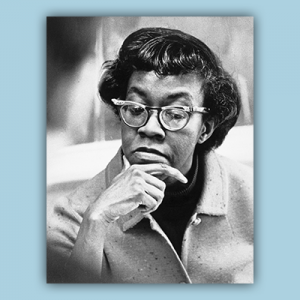

IN “KITCHENETTE BUILDING,” Gwendolyn Brooks, the first Black Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, considers the challenge of dreaming in grim places. The setting of this 1945 poem, published as part of Brooks’ first collection, A Street in Bronzeville, is the titular kitchenette building, a housing unit of many cramped, run-down apartments, often rented by Black residents in that era in cities like Chicago. Tenants are “grayed in, and gray,” worn out by systemic injustice and the demands of daily life, such as paying rent and putting food on the table. Still, the speaker — who speaks on the behalf of a collective “we” — wonders if a dream could rise “through onion fumes” and “sing an aria” in the building.

The dream in “kitchenette building” is delicate and “fluttering,” something that requires time and contemplation — luxuries that systemic oppression makes nearly impossible. Brooks’ biographer, Angela Jackson, in A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks, describes this poignantly: “Life is grim in these kitchenette buildings ... entrapment as in a prison. People here are not people; they are things, dehumanized by the nature of a system they did not volunteer for.” Later, she asserts that kitchenette residents “cannot even consider” a dream greater than a cold bath “[before] a realistic necessity comes up ... They take what they can get.”

Brooks makes it clear, though: Imagination is a vital precursor to liberation. “Kitchenette building” plants seeds in questions: What would happen if dreams of freedom and freshness had space to grow? What would liberation look like for Black communities and the U.S. as a whole?

How the Ocean Heals Us

“Rewilding” Christianity through new forms of outdoor Eucharistic life.

THIS SPRING, I moved to California. Nature, culture, family, and work beckoned my partner and me, and once we arrived, we found ourselves immersed in sweetness: picking roses in our friend’s garden so fresh they smelled like citrus; sharing weekly dinners with my brother; and swimming in the Pacific Ocean. In that water, I’ve felt swallowed by mystery. The airborne salt, the bone-cold temperature, and the wild waves refine my ability to listen to the hum of the earth. In the Christian tradition, the ocean’s role in shaping consciousness is robust. Through their writing on “contemplative ecology” and reflections on the Pacific, contemplative theologian Douglas E. Christie, Lutheran scholar Lisa E. Dahill, and mystic Thomas Merton have helped me embrace the ocean as a healing partner.

Christie, author of The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology, describes “contemplative ecology” as dual-natured: a spirituality that centers the natural world and “an approach to ecology” that relies on “contemplative awareness.” He posits that connecting contemplation to the environment helps make us more “porous,” more attentive, and clearer about the world as a “sacred [and beautiful] whole.”

It is especially important, and equally challenging, to see the world as sacred and beautiful amid the global climate crisis.

How Do You Re-Tell a Story That Has Been Told the Wrong Way?

Without public memory to anchor and unite us, nostalgia and racism distort our storytelling and education.

IN 2015, I visited two plantations in rural Louisiana to write a college paper on white supremacy. One, Whitney Plantation, centered the experiences of enslaved people by sharing “firsthand accounts” and including statues of and memorials to them. The other, Oak Alley Plantation, romanticized the Antebellum South. Filled with indignation, I could not fathom how tourists at Oak Alley drank mint juleps where brutality, violence, and terror once reigned. Clint Smith, author of How the Word Is Passed, studies sites of racialized violence in the U.S. to help form a more accurate American “public memory.” We need Smith’s poetic-sociological vision to help us tell the true, humanizing stories of our — often ugly — history.

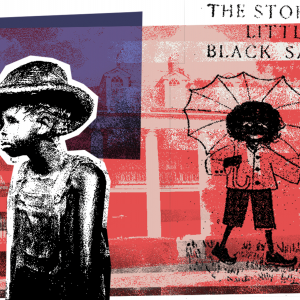

During my visit, Oak Alley sold copies of Little Black Sambo by Scottish author-illustrator Helen Bannerman in its gift shop (the shop no longer sells this title). A racist children’s book about a family that is widely understood to be Tamil, the 1899 children’s book portrays dark-skinned Indian people through heavy “pickaninny” caricature. In the book Racial Innocence historian Robin Bernstein explains, “The pickaninny was an imagined, subhuman black juvenile who was typically depicted outdoors, merrily accepting (or even inviting) violence.” The dangerous trope desensitizes us to violence against Black and brown children, evidenced throughout history from slavery to police brutality. My family is part Tamil, and I nearly choked when I saw this “artifact” of dehumanization dressed up as nostalgia.

What Happens When You Imagine Peace?

The arts help us operate outside of the conditions that fuel dehumanization.

IN PEACEBUILDING AND THE ARTS, practical theologians Theodora Hawksley and Jolyon Mitchell ask readers to imagine peace: “It is all too easy to reach for clichés” — doves or peace signs come to mind — or “to think of peace as a sort of absence, a not-happening.” In our violent world, we readily picture conflict and injustice, but not peace or conflict transformation. The arts help us fill this empty space, revealing the true nature of peacebuilding as “an ongoing, dynamic process, a journey that sets human relationships on the road to life.” Through bolstering the moral imagination, the arts rehumanize dehumanized contexts.

Mitchell explains how the arts give us “realistic visions of how to create peace” and foster “an environment in which the ‘moral imagination’ can be cultivated.” He shares the example of Mozambican Anglican Bishop Dinis Sengulane, who, in the mid-’90s, established the Transforming Arms into Tools project after the end of Mozambique’s long civil war. This project asked local artists to “glorify peace” through refashioning decommissioned weapons into art. Compelling works such as “Throne of Weapons” (2001) and “Tree of Life” (2004) emerged: metallic sculptures made from assault rifles welded together in a way that preserved the outlines of the weapons. The “Throne of Weapons” has a back, arms, seat, and legs made clearly from the barrels, triggers, and heels of AK47s. The viewing experience is a dance between the parts and the whole, which underscores the meaning of the project itself. The sculptures represent the specific horrors of the past and broader hope born from peacebuilding. Displayed in public places in the U.K., these works have served as a caution against gun violence and an inspiration to activist-artists across the globe.

The Quiet Wisdom of the Wounded Healer

A new paradigm for leadership from Henri Nouwen’s 1972 book.

IN THE WOUNDED HEALER: Ministry in Contemporary Society, Catholic theologian and priest Henri J.M. Nouwen analyzes how the church fails to address the heart of our collective pain and longing. Nouwen presents a paradigm for renewed Christian leadership and care founded on the archetype of the “wounded healer.” More than 50 years after the publication of The Wounded Healer in 1972, we continue to struggle — both individually and societally — with the “wounds” Nouwen names: alienation, separation, isolation, and loneliness. Whether we’re ministers or not, we need the gentle wisdom of the wounded healer to build a more loving, just world.

While the concept goes back at least as far as Plato, the term “wounded healer” was coined by psychoanalyst and doctor Carl Jung. To demonstrate the link between personal suffering and the capacity to care for others, Jung draws on the Greek myth of Chiron. Chiron is a centaur who, due to severe physical pain, becomes an important healer and teacher. Nouwen extends this principle to ministry, calling for church leaders to cultivate “a deeper understanding of the ways in which [they] can make [their] own wounds available as a source of healing.” For both Jung and Nouwen, this work develops depth and compassion. Nouwen writes, “For a compassionate [person] nothing human is alien: no joy and no sorrow, no way of living and no way of dying.”

Reflections After a Spiritual Crisis

Healing can be found even in that which seems like oblivion.

IN MY FIRST SEMESTER of divinity school, I experienced a spiritual crisis. For months, I woke every night at 3 a.m., plagued by unanswerable questions on life’s meaning, God’s silence, suffering, and human nature. At the time, I felt alone, but now, years on the other side of it, I see the healing that emerged from my “dark night of the soul.”

While the phrase “dark night of the soul” has seeped into secular parlance, it is specifically drawn from the Christian contemplative tradition. St. John of the Cross, a 16th-century Carmelite monk and reformer, wrote a theological commentary and a poem, both titled “The Dark Night of the Soul,” about good darkness, contemplation, and the journey of faith. These works emerged after John’s unjust imprisonment in a monastery, where he endured physical violence and extreme deprivation. There, John discovered the richness of the “dark night” for illumination and purification. Barbara Brown Taylor, author of Learning to Walk in the Dark,writes, “For [John], the dark night is a love story, full of the painful joy of seeking the most elusive lover of all.” While the dark night may feel like “oblivion,” John contends that “The more darkness it brings ... the more light it sheds.”

Reclaiming Weeping as a Sacred Practice

Amanda Held Opelt's new book explores the lost rituals of grief.

IN THE 15TH CENTURY, Margery Kempe received the divine gift of weeping. When considering the multitude of spiritual powers God has bestowed — prophecy, healing, and discernment, for instance — weeping is a peculiar one. After several transformative visions, Kempe, an English laywoman and mystic, wept regularly in hourslong sessions out of contrition for human fallenness and compassion for Christ’s suffering. St. Jerome visited her to convey that God had given her a permanent “well of tears” to help others. Consequently, she developed a form of sanctifying prayer, weeping “on others’ behalf” to help liberate them from sin, purgatory, anguish, or death. Kempe’s fervor continues to demonstrate the place of tears in daily life. Even for us non-ascetics, tears express truth, helping us attune to the wisdom within and beyond us.

Some of Kempe’s contemporaries thought her weeping (which evolved into a decade of “roaring”) to be disruptive, odd, or performative. And as Oxford professor of English Santha Bhattacharji explains in her article “Tears and Screaming: The Spirituality of Margery Kempe,” those critiques continue today. Some scholars have labeled Kempe as “extreme” or “hysterical,” characterizations that ring of misogyny. Nevertheless, her practices were church-approved and part of the well-worn tradition of Christian tears. The Desert Mothers and Fathers considered crying an “official form of worship.” The Rule of St. Benedict stipulates that tears are the mark of “pure prayer.” Tears — whether quiet or loud — are expressions of the heart that connect us to divine wisdom. As Eastern Orthodox theologian Kallistos Ware writes in his article “‘An Obscure Matter’: The Mystery of Tears in Orthodox Spirituality,” “We weep [to give] expression to the intimate feelings that are ‘too deep for words.’”

‘The Dinner Party’ Reminds Us of What Patriarchy Erased

In the famed feminist art installation, Sophia stands as a cross-cultural symbol of a female God.

IN RATTLING THOSE DRY BONES: Women Changing the Church, activist and author Susan Cole writes an essay in response to the question, Why do I remain in the church? In her answer, she shares how she healed her relationship with God through the figure of Sophia, who she defines as “the Wisdom of God, the divine imaged as female.” Cole writes, “Through [Sophia] I have discovered in a whole new way, divine presence within myself, within my sisters, within all that is.” Cole’s portrait of a female God, filled with kindness and joy, stands in stark contrast to the millennia of androcentrism that shapes Christian teaching and practice. The treasure of the Christian female godhead remains buried, but it can be uncovered.

Sophia sits (metaphorically) at artist Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” the famed feminist installation anchored by an enormous triangular banquet table, 48 feet long on each side. From 1974 to 1979, Chicago scrupulously created unique, historically precise place settings for 39 “guests of honor,” female figures both mythical and historical, ranging from Mother Earth to Georgia O’Keeffe. An additional 999 names appear written on tiles surrounding the table. According to Brooklyn Museum curators, at Chicago’s table Sophia stands as a powerful “creative force in the universe” and a cross-cultural symbol of a female God. And the elements of Sophia’s place setting — a flower plate with watery petals and a runner made from remnants of a wedding veil — symbolize Christianity’s role in “the downfall of female power, particularly religious power.” On a grand scale, “The Dinner Party” reminds us of what patriarchy has erased.

Embracing Embodiment with Julian of Norwich

The mystic anchoress who envisioned human wholeness.

JULIAN OF NORWICH, the 14th-century anchoress and mystic in England, prayed for an embodied understanding of suffering. As she wrote in Revelations of Divine Love, she desired “three graces” from God: “to relive Christ’s Passion”; “bodily sickness”; and the wounds of “contrition,” “kind compassion,” and “purposeful longing for God.” At age 30, on what she presumed to be her deathbed, Julian received a series of divine visions — equally euphoric and terrifying — that taught her about the all-encompassing nature and nearness of God’s love. In one vision, Julian saw Christ’s head bleeding profusely from the crown of thorns.

But these images did not bring her a message of despair. Julian wrote, “This is our Lord’s will: that we yearn and believe, rejoice and delight, take comfort and console ourselves as much as we can, with his help and his grace, until the time when we can see it truly for ourselves.” Through pain and contemplation, she developed a deeply embodied faith. Reading her work healed years of spiritual pain for me. In the Catholic context of my upbringing, shame led to disembodiment and antagonism toward my body. Julian, by contrast, envisioned human wholeness — in mind, body, and soul.

Drawing Out the Infinite in the Infinitesimal

Vija Celmins' lithographs inspire us to live out a posture poised for awe.

THERE'S A REFORM JEWISH Sabbath prayer that reads, “Days pass and the years vanish, and we walk sightless among miracles. Lord, fill our eyes with seeing and our minds with knowing; let there be moments when Your Presence, like lightning, illumines the darkness in which we walk. Help us to see, wherever we gaze, that the bush burns unconsumed. And we, clay touched by God, will reach out for holiness, and exclaim in wonder: ‘How filled with awe is this place, and we did not know it!’”

If we want to experience awe or wonder, we need to reach for inputs of wisdom that enliven our ways of seeing. As a person who struggles with overthinking and anxiety, I find visual art, like the work of Latvian American artist Vija Celmins, to be instructive. “The thing I like about painting, of course,” Celmins said in an interview with the Tate museum, “is that it takes just a second for the information to go ‘bam,’ all the way in, and then you can explore it later.” Engaging with Celmins’ work teaches me how to pay close attention to the life in front of me, noticing the beauty that pervades everything.

The 11-Foot Puppet Traveling ’Round the World

Little Amal has traversed more than 5,500 miles to share a poignant plea: “Don't forget about us.”

LITTLE AMAL, an 11-foot-tall puppet of a 10-year-old Syrian refugee, is the star of “The Walk,” a live public production to honor millions of displaced children in the world. Named after the Arabic word for “hope,” Amal took her first steps at the Turkey-Syria border in July 2021. Since then, she’s traversed more than 5,500 miles in 13 different countries to share a poignant plea: “Don’t forget about us.”

Four puppeteers help Amal walk. One person sits inside her torso, visible through a cage, to operate her face, head, and feet; two move her hands with external rods; and one offers balance support from behind. Amal towers over the crowds who greet her, and the enormous space she occupies sends a powerful message: Forced displacement is an urgent and collective responsibility. The Walk embodies compassion, care, welcome, and belonging — core principles of Christianity. Amal, who has more than 170,000 followers on Instagram, has become a well-recognized humanitarian symbol, reminding us that displaced people are not “aliens” or “strangers.” They are our siblings, parents, children, neighbors, and friends.

Reclaiming Advent as the Season of the Midwife

As we anticipate the birth of Jesus Christ, we must remember that God appeared in these tender places — in human flesh, in the womb of a refugee, at the site of vulnerability and oppression.

IN THE EIGHTH season of Call the Midwife, set in post-war east London, nuns and nurse midwives of Nonnatus House assist a woman with severe complications from a “backstreet” abortion. Sister Julienne says to a young nurse, “The word ‘midwife’ means ‘with-woman.’ A woman in that situation needs somebody by her side.”

I’m pro-choice, which was an unpopular stance in the Catholic community I grew up in. For my views on reproductive rights, people in youth group called me a “baby killer” and “Pontius Pilate.” During Advent, specifically, I loathed the hollow teachings on Mary and childbirth. We sanitized the Nativity into a cute story — the equivalent of a Disney movie featuring a white family and a manger crowded with men. Only recently did I learn that some scholars believe that midwives attended Jesus’ birth. As reproductive freedom and care are further undermined in the United States, this is an apt time to reclaim a more feminist view of the Nativity and rethink Advent as the season of the midwife.

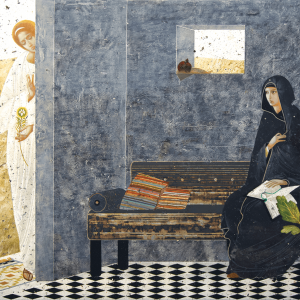

Seeking God’s Wisdom Through ‘Visio Divina’

The contemplative practice that renews our capacity to see.

AT THE START of the war in Ukraine, images overwhelmed me. Families crowding onto trains. Teachers holding assault weapons. Nigerian students being held at the border. The clash of human tenderness with extraordinary aggression was arresting. In between checking updates from a friend—an art curator sheltering in Kyiv—Instagram suggested I follow Lviv-based contemporary icon artist Ivanka Demchuk. With fears of global annihilation humming in my head, Demchuk’s fresh, calming pieces, such as “Annunciation” and “Sophia the Wisdom of God,” captivated my attention and softened the edges of my growing despair.

In recent years, Lviv has become a hub of Christian sacred art technique and production. Lviv National Academy of Arts, from which Demchuk graduated, teaches icon creation, sacred space decoration, and icon theology. For centuries, icons helped make Christianity accessible to illiterate populations. But today, it strikes me that we need this life-giving artform in new ways. We are inundated with photographs of violence, from destruction in Ukraine to police brutality in our neighborhoods. Jesus Christ, our Wounded Healer, taught his disciples how to see injustice and move toward it. How can we, as Christian people committed to justice, cultivate these twinned capacities—seeing clearly and seeking social healing—within ourselves?