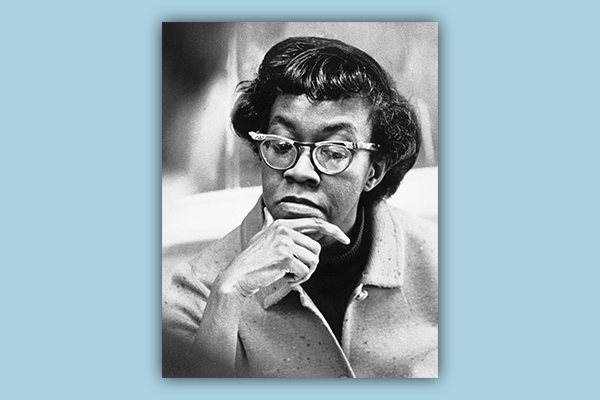

IN “KITCHENETTE BUILDING,” Gwendolyn Brooks, the first Black Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, considers the challenge of dreaming in grim places. The setting of this 1945 poem, published as part of Brooks’ first collection, A Street in Bronzeville, is the titular kitchenette building, a housing unit of many cramped, run-down apartments, often rented by Black residents in that era in cities like Chicago. Tenants are “grayed in, and gray,” worn out by systemic injustice and the demands of daily life, such as paying rent and putting food on the table. Still, the speaker — who speaks on the behalf of a collective “we” — wonders if a dream could rise “through onion fumes” and “sing an aria” in the building.

The dream in “kitchenette building” is delicate and “fluttering,” something that requires time and contemplation — luxuries that systemic oppression makes nearly impossible. Brooks’ biographer, Angela Jackson, in A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks, describes this poignantly: “Life is grim in these kitchenette buildings ... entrapment as in a prison. People here are not people; they are things, dehumanized by the nature of a system they did not volunteer for.” Later, she asserts that kitchenette residents “cannot even consider” a dream greater than a cold bath “[before] a realistic necessity comes up ... They take what they can get.”

Brooks makes it clear, though: Imagination is a vital precursor to liberation. “Kitchenette building” plants seeds in questions: What would happen if dreams of freedom and freshness had space to grow? What would liberation look like for Black communities and the U.S. as a whole?

Read the Full Article