Arts & Culture

Communal Sin

The psychological thriller God’s Creatures follows a mother who chooses to hide her son’s secret, a decision that has damaging ripple effects in her remote fishing village. The film explores how a community’s complacency in covering up sin can systematize and amplify evil.

A24

P-VALLEY IS A DRAMA about employees of a fictional strip club in Mississippi called The Pynk. Watching the show, which Starz has renewed for a third season, gives me déjà vu. In the opening minutes of the first episode, we see a neighborhood overtaken by a flood, the camera eventually focusing on a floating suitcase — which a woman who looks like she just survived a hurricane grabs. I’m reminded of Toni Morrison’s titular character Beloved, who “walked out of the water”; it’s all instantly reminiscent of the Southern, sin-filled aura of stories by Flannery O’Connor. A few minutes later, I’m hit with production design as colorful as that of the TV show Pose — unabashed theatricality.

This description should feel as dizzying as twirling around a stripper pole — that’s the inevitable impact of the artistic and spiritual heft P-Valley wields. The show, which is an adaptation of a play by Pulitzer Prize winner and Tony Award nominee Katori Hall, is about nothing less than free will. Hall explores complex topics such as sex work, abuse by men, abortion, and homophobia. Here in the Mississippi Delta, viewers get to know a mostly Black community trying to live as freely as the Constitution of their nation built by slaves declares white men should.

IT WOULD HAVE been tough to be both a disciple of Jesus and a foodie. Don’t get me wrong, Jesus certainly valued food — his earthly ministry was filled with meals: The gospel of Matthew describes Jesus as one who “came eating and drinking” (11:19). As Robert J. Karris wrote in Eating Your Way Through Luke’s Gospel, Jesus was “either going to a meal, at a meal, or coming from a meal.” But what the Chosen One had in meal frequency, he lacked in meal diversity.

A “foodie” is someone who eats food as a hobby — a passion, even. The more exotic the better. If you pull up to your local boba shop, why settle for regular milk tea when you can order one infused with butterfly pea flower that turns it bright blue?

However, for Jesus’ meals, at least the ones recorded in scripture, the fish is served broiled (Luke 24:42), not creatively deconstructed. And if you’re rolling with Jesus, you better like eating bread.

Though his plate may have lacked the splendor of the centurions’ or high priests’ spreads, Jesus viewed the table as a radical place of inclusion. For many powerful religious leaders of the time, dining was yet another way to shun the outcasts. In contrast, Jesus intentionally invited those very same “unclean” people to dine with him, breaking bread (because of course it was bread) with tax collectors, sinners, and prostitutes.

In the past year, several films have articulated a hunger for the type of table Jesus championed. Flux Gourmet, Triangle of Sadness, and The Menu critique class inequality through stories revolving around fine dining. In each movie, wealthy people have rich flavors but a dearth of meaningful relationships. The exclusivity of the table seems more important than the actual food served on the plates. Jesus’ table, on the other hand, lacked variety but overflowed in inclusivity — a true palate cleanser to meals that symbolized selfish consumption.

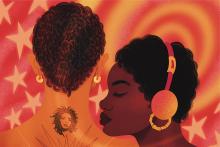

MUSIC IS MY safe space. When all hell is breaking out, I can put in my AirPods and turn on part of the soundtrack of my life and reset. The pandemic created a chronic hell that illuminated oppressive forces that have existed for centuries. Music became even more essential for my survival.

I am a Black clergywoman who is clear that “my emancipation doesn’t fit” many people’s equation. Let me say that another way: My authentic expression of self makes some people uncomfortable. My unapologetic expression of womanist Blackness often sheds light in the shadows of a corrupt world.

I won’t pretend that I have always felt free to be me. It took a pandemic to give space to be reminded by theologian and prophet Lauryn Hill that “deep in my heart, the answer, it was in me.” Hill’s lyrics and very existence compelled me to “[make] up my mind to define my own destiny.”

Some consider Hill to be one of the greatest lyricists of all time. An eight-time Grammy winner (with 19 nominations), she sings, raps, and acts. She is hip-hop royalty. In the ’90s, I wanted to be her. She wore the dopest locked hair style, had the most beautiful brown skin, and expressed her Blackness with boldness and class. She had, and still has, a lyrical flow that men and women couldn’t ignore. She was fly. (Translated as cool, sexy, smart, and stylish.)

Her industry-shaking debut solo album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, released in August 1998, will stand the test of time. Hill speaks truth in ways that penetrate the soul. I was a young mother when the album came out. She articulated things that only a Black woman could identify with. She spoke of the tension and beauty of having a child when society was telling her that motherhood and a career couldn’t coexist. She sang and rapped about self-respect, love gained, and love lost. This album is life. This album ministers. This album is sacred.

DNA RESEARCH HAS been a sacred journey of mine for the last 10 years. What started as an exercise in building my family tree evolved into a global adventure unearthing my West African roots. Little did I know that more than 50 percent of my ethnic heritage traces back to West Africa through Nigeria, Benin, and Cameroon (connected to the Bamileke people).

The African roots of the Puerto Rican story often remain obscure. Like many Puerto Ricans, I was taught a one-dimensional story of my heritage. Puerto Ricans often, with beaming pride, share their connection to the cultural heritage of Spain or their Indigenous roots, namely the Taino Indigenous peoples. But, for many, the African strands of identity are held at a distance, even suppressed like a muted djembe beat.

Black Dignity is a must-read for anyone struggling against domination in a world constituted by anti-Blackness. For Lloyd, domination is the arbitrary exertion of one’s will over another, and its “primal scene” is the master/slave relation. For Lloyd, his use of the language of “domination” points toward a specific kind of relation that permeates the world: anti-Black violence. Lloyd specifically says the purpose of the book is “to get a sense of this new language of Black dignity, to explore how the hashtags could be filled out, linked together, and oriented toward the struggle against domination in general and anti-Blackness in particular.” Morally stimulating, energizing, probing, and clear, Black Dignity demonstrates Lloyd’s ability to weave together and synthesize Black political and religious thought.

Churches far too often operate under the “male gaze.” The male gaze, a term I'm borrowing from film criticism, always answers the question of “Who is this for?” with “Well, men, of course.” Some congregations, even though they affirm women pastors, worship directors, and singers, still caution them to dress so that the men in the congregation don’t find them “tempting.” The male gaze is always cisgendered and heterosexual, so churches that are formed by the male gaze are structured to be hostile toward queer people (no matter how kind congregants in those churches are to queer individuals).

The 1992 classic is full of wonders you can’t find anywhere else: Michael Caine starring in a children’s movie, a ghost of Christmas future that haunts me every time I consider splurging on frivolities, and a drum set at a Victorian England Christmas party. But the movie isn’t just a fun, Muppet-y take on Charles Dickens’ classic novella; it’s also a compelling screenplay with heart-warming, humorous songs that offer a radical Christmas message of “cast down the mighty … send the rich away empty.”

The list below reflects my own preference for films and shows that help me leverage my own viewership to sustain a lifestyle of equity and inclusion. I’ve included 10 films and shows that gave the spotlight to communities, issues, and stories that we usually don’t see — and how richer the world is because of them.

“Find those who tell you, Do not be afraid, yet stay close enough to tremble with you,” writes Cole Arthur Riley in This Here Flesh, “This is a love.” Here are 12 books from 2022 — nonfiction, memoirs, novels, and short stories — that we think are worth keeping close.

Brandi Carlile noted the U2 artists’ and Grant’s support for LGBTQ rights while representing their Christian faith to the world.

I was wrapping up some research in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University when I requested a box of Lucille Clifton’s personal writings. I had not come to study Clifton. I was researching anti-lynching activism in Georgia, specifically a 1936 lynching photograph. But by the end of the week, I began turning to Clifton’s personal writing as an oasis. “Resolve to try to fear less and trust more and be healthy,” she wrote in her red Writer’s Digest Daily Diary on December 31, 1979. Clifton was a published children’s book author, memoirist, activist, and the poet laureate of Maryland when she wrote those words. She was also 43, the same age I was that September day. Her body of work, which includes Two-Headed Woman and Blessing the Boats, crossed oceans, told family stories, and revealed both the sting of injustice and the heart of what’s holy.

The day after Clifton resolved to “fear less and trust more and be healthy,” she wrote in her journal that she returned to a house with “no central heat; bad plumbing; and foreclosure.” A few weeks later, the house was auctioned off to the highest bidder. She sat down and wrote something anyway.

ART CONSERVATIONALISTS RECENTLY discovered a previously unknown Vincent van Gogh painting, a rare find that has excited the art world. On the back of his 1885 portrait “Head of a Peasant Woman,” tucked beneath layers of cardboard and glue, is a hidden self-portrait from early in van Gogh’s career, before he famously cut off his left ear. But the discovery is significant for more than its artistic importance. The hidden self-portrait is symbolic of van Gogh’s larger life and works, illustrating his Christian faith, compassion for the poor, and lifelong struggle with religious rejection.

Van Gogh grew up attending church and wanted to become a clergyman, just like his father, Rev. Theodorus van Gogh. But these hopes were dashed when he was unable to enter religious studies, in part because of behavior considered “eccentric” — a sort of manic shifting of interests. This was an early manifestation of van Gogh’s lifetime of mental health struggles, and the beginning of a complicated relationship with the church.

What moved me the most was a tiny hand,

like the claw of a cub, pawing at my

rib cage in time to the suckle of his lips.

This beautiful, wild person sustained

by milk drawn from unknown wells within me.

I remember nursing once in the basement

restroom of the zoo’s primate house.

The floor tile was cold — no other place to sit.

I RECENTLY SUFFERED a home invasion by one of the Four Rodents of the Apocalypse, which are mice, rats, squirrels, and something called “roof rats” (rats tired of the climate-change-induced uptick in flooding of sewer-front properties). I was blessed with the deceptively cutest of these four: Squirrels. In. My. Ceiling.

(Reader, I want to be clear that “squirrels in my ceiling” is not a reference to my scattered thoughts but to literal bushy-tailed rodents doing tumbling runs in the crawl space above a bedroom.)

Squirrels strike a rare balance: They are both adorable and terrifying (like some toddlers I know). One day they’re hanging upside down outside the window to say hello or sitting and nibbling on a nut held just so in their wittle paws, so winsome! The next, a squirrel appears out of nowhere as I enjoy a sunny day on my front stoop, its eyes locked on mine. It skitters forward, then freezes. Forward and freeze, forward and freeze, like a glitchy squirrel robot. It is undeterred by “Shoo!” or “What do you want from meeeee?” Staring blankly, it just keeps coming — for the peanuts it imagines are in my pockets? For my soul? Or are there now flesh-eating squirrels? I run inside and lock the door.

Day is who Mayfield looks to when her soul is parched and she longs to be renewed with God’s love “in order to keep going.” I found Unruly Saint spiritually nourishing in this way: It wrestles with the questions of how we keep going, how we keep having hope in our exhausting world, how we keep our inner light burning. “She wanted to keep a flame lit for people wondering how to break the cycles of war and oppression built into our histories and hearts,” Mayfield writes.

“THE SPIRITUAL LIFE, in other words, is not achieved by denying one part of life for the sake of another. The spiritual life is achieved only by listening to all of life and learning to respond to each of its dimensions wholly and with integrity.”

In this quote from Wisdom Distilled From the Daily: Living the Rule of St. Benedict Today, Joan Chittister writes about living a spiritually active existence that fully engages with our daily reality. She couldn’t have known it at the time, but Chittister might as well have been describing one of the biggest pop culture trends of the last few years: the multiverse.

The concept of multiple worlds and multiple versions of ourselves (some of whom live the life we secretly wish we had) has become ubiquitous across screens, from movies like Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness and Spider-Man: No Way Home to TV shows like Rick and Morty and Doctor Who. Perhaps the example of multiverse storytelling to most successfully plumb emotional possibilities so far — listening to all of life and responding to its dimensions with integrity — is also one of 2022’s most surprising hits: the indie film Everything Everywhere All at Once.

Divine Justice

A Comanche woman eschews gender norms to protect her tribe from fur trappers and alien warriors in the sci-fi horror film Prey. The movie honors Indigenous culture and offers a compelling, brutal picture of divine justice against colonial powers.

Hulu

INDIE-ROCKER MAGGIE Rogers says she feels her emotions in her teeth: Anger and love make her gums pulse and jaw tighten. Rogers’ second studio album, Surrender, is testament to what happens when we unclench our jaws and give our emotions room to breathe.

“This is the story of what happened when I finally gave in,” Rogers said in the trailer for Surrender. The result is a cohesive journey through the many questions that plague our grief-stricken culture. Offering both solace and space for unanswered questions, the album, released last summer, is an invitation to dance — to surrender to the coexistence of beauty and suffering in the world.

REVELATION IS AN intimidating book of the Bible to understand, let alone apply to everyday life. Dense with symbolic imagery and metaphors, it has been subject to innumerable interpretations and far-flung theories. But what are we to make of startling moments in the text, like when Jesus regurgitates a sword or John eats a scroll? In Upside-Down Apocalypse: Grounding Revelation in the Gospel of Peace, author Jeremy Duncan walks readers through Revelation by drawing parallels between the genres and figures of speech of John’s day and ours, lending clarity to how John’s apocalypse is deeply steeped in Jewish literary tradition and Roman culture. When we ignore this context, we miss the point of the final book of the New Testament: Revelation is not the wrathful reckoning of a conquering king; rather, as Duncan writes, it’s a testament to “how the Prince of Peace turns violence on its head once and for all.”

With each chapter, Duncan decenters “chrono-centric” approaches to Revelation, encouraging readers to avoid reading the text as “a story about me and my world and my time exclusively.” As the perfect, timeless witness of God, Jesus must be the guiding principle by which we understand all of scripture. Only then can we appreciate how God’s kingdom in Revelation contrasts with earthly kingdoms fueled by oppression. “[E]very time you awaken to how empire is trying to steal your imagination and make you believe in violence,” Duncan writes, “you have rightly interpreted Revelation regardless of the time period in which you awake.” Revelation asks us to watch for injustice, wherever and whenever it appears.