intersectionality

Lloyd, a theologian and director of Africana studies at Villanova University (and Sojourners contributor), writes about his experiences teaching a seminar on “Race and the Limits of Law in America” through the Telluride Association. In the blistering essay, Lloyd writes that he experienced a “mutiny” — expelled from his role by his high school students led by a “charismatic” college-aged student who created a “cult” of anti-racism and eventually accused him of harm, micro-aggressions, and perpetuating “anti-black violence” through the seminar.

Maybe it was Rev. William Barber’s preaching that touched me with the moral call to climate justice, in partnership with Al Gore, whose organization Climate Reality Project brought this audience together for a three-day training. Later that night, I realized why the message felt personal: Barber pushed me to reframe my conversations with my daughters about climate justice in this country. I teach environmental education at a small college in North Carolina, but the way I communicated at home around the kitchen table needed a transformation.

WOMEN IN almost every culture and segment of society experience violence ... that is directed specifically at them as women. In the United States, women of color—Latina, African American, Asian, and Native American—experience violence that is specifically focused against them because of both their race and their gender. When misogynist violence combines with racism, the result is a unique and deadly threat to women of oppressed races. ...

Women of different races and economic backgrounds have begun to join together in a movement to end the violence that endangers them all. The women of color who are involved in this movement, however, bear witness to the barriers that hinder such cooperation. Prominent among them is the misunderstanding or ignorance of the particular ways that both individuals and institutions perpetrate violence focused against women of color. It is clear from the historical and current experiences of women of color that racism is an inextricable factor in this violence. They reject, therefore, analyses that blame only sexism and patriarchal structures for violence against women. The problem of misogynist violence can only be fully addressed when the experiences of all women are incorporated into the perspective of the movement for change. Both racist and anti-women stereotypes and attitudes must be overcome before society can become a safe place for all women.

Another issue that we know: In a number of states, pregnant women, when they give birth in the midst of their sentences, they’re forced to be shackled to a gurney in the midst of their delivery process. We know being born into that stress-induced state has irreversible cognitive impacts on the child, but we still haven’t changed the law in light of that.

THE TONYA HARDING saga was a Great American Novel of the 1990s waiting to be written—equal parts Theodore Dreiser and Three Stooges. Harding was the impoverished striver who muscled her way to the top of the hoity-toity world of women’s figure skating, only to be disgraced when her ex-husband’s buffoonish associates carried out a bizarre assault on a rival skater, Nancy Kerrigan.

The film I, Tonya delivers this story well, both as tragedy and as farce. It shows us the particular violence of frustrated hopes, malnourished emotions, and internalized self-hatred that passes from generation to generation like a plague in the lives of poor white people in America.

In 1972, when Tonya Harding was 2 years old, sociologist Richard Sennett and Jonathan Cobb published a book called The Hidden Injuries of Class. That phrase kept running through my mind as I watched I, Tonya. Sennett and Cobb profiled white working-class Americans who felt the pain of being disrespected and looked down upon, yet couldn’t help blaming themselves for that fact. One of their interviewees remarked, “I really didn’t have it upstairs to do satisfying work.”

Less than two years after Sennett’s book arrived, LaVona Golden, a foul-mouthed, chain-smoking wraith of a waitress (played by Allison Janney), intimidated a WASPy skating teacher into taking her daughter Tonya as a student. From that point on, in the movie, the girl’s life is blur of skating and abuse. Her mother torments her into giving her best on the ice, but comes up empty on empathy or affection. And the abuse gets physical. As a teenager (played by Margot Robbie), Tonya moves out to live with her boyfriend and ex-husband-to-be, Jeff Gillooly, and he hits her too.

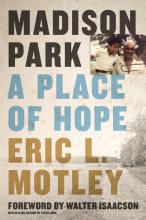

Eric L. Motley, former special assistant to George W. Bush and current Executive Vice President of the Aspen Institute, shares on the hard knocks and treasures of growing up in a largely poor African-American town during the height of the civil rights era in his memoir Madison Park: A Place of Hope. In the memoir, Motley chronicles his journey from a rural town founded by freed slaves in Alabama to navigating the political terrain of the White House. Motley recounts formative and disappointing experiences around the issue of race and highlights some of the small-town heroes that poured into his life as a child. The memoir provides a thoughtful reflection of how faith and radical love within a tight-knit community can significantly impact a person’s life.

Motley recently spoke with Sojourners about his story.

Sure, there are loud voices that seem to feed into certain conclusions about what religious people think about science and scientists. (Consider creationist Ken Ham’s attempts to discredit the theory of evolution.) But, as with any issue, the loudest or most prominent voices are not necessarily the most representative.

During that time, there have been reports of at least three miscarriages by women in detention "due to mistreatment and medical neglect, a cruel trauma that no expecting mother should have to endure," the members wrote.

On Jan. 21, more than 1 million women and men around the world rose up and became part of a resistance.

Here are just a few of those faces — six people who showed up to make their voices heard at the Women's March on Washington. They each marched for individual reasons, but found common ground among the crowd.

The reality of our privilege is that it makes many truths of systemic injustice unclear to us. We fumble around with murky awareness and bump into our own ingrained racism and ignorance. As allies, the question for us is not if we will screw up, but how we will move forward when we inevitably do.

The reality is that modern Christianity in the Americas was built upon the genocide of indigenous people, the theft and commodification of land, and the enslavement of black people. It wasn’t simply an ethical glitch of bad people with otherwise good theology. No. This was praxis, linked with liturgy, linked with worldview, and, beyond that, to imagination. Will you continue to believe that modern “Christianity” is essentially good but was simply misused by bad people? Or, will you have the unflinching courage to critically examine Christianity’s role in horrors, in inequality, even in your own alienation?

Disability is an incredibly salient and important part of this story, particularly in the reporting – portraying Kinsey as a hero simply for working around disabled people, or framing the situation as horrifying because it involved a disabled person, as though we are innocent from reality.

Bree Newsome, a Christian activist from North Carolina, climbed into history last year when she scaled the flagpole of the South Carolina state house and removed the longstanding Confederate flag. One year later, Sojourners caught up with Newsome, an honoree at The Summit 2016, on what her action helped bring down — and build up.

The most important political fact in America is that, in just a few decades, we will no longer be a white majority nation but a majority of minorities. The milestone historical realities of that fundamental demographic shift are underneath everything else in American politics. Race is an intersectional issue in our political discourse today.

As Christians, our response to the changing demographics of America should be two-fold: a renewal of our baptism and a renewal of democracy.

FAITH-BASED COMMUNITIES have been at the forefront of environmental justice work since the phrase first came into use. In 1987, the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice published the report Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. The report—the first of its kind—documented the connection between the siting of hazardous waste sites and the race of the communities where they were located.

For Aaron Mair—an epidemiological-spatial analyst with the New York State Department of Health—environmental justice organizing began in 1984 when he and his family moved to the Arbor Hill neighborhood of Albany, N.Y. The 80-percent-black neighborhood was home to an incinerator that resulted in two of his daughters having upper-respiratory health issues, according to Mair. The neighborhood’s toxic air prompted Mair to begin organizing his community to get the incinerator shut down.

In May 2015, Mair was elected as the first African-American president of the Sierra Club, a national environmental organization with more than 800,000 members. Raven Rakia, a freelance journalist and Grist fellow, interviewed Mair for Sojourners in February.

Raven Rakia: What’s the significance of your becoming the first black president of the Sierra Club?

Aaron Mair: I didn’t start out to make history with the Sierra Club. I started out to make history as an environmental justice activist by elevating the voice of communities of color with regard to equal treatment and protection under the law.

I think there is a very real need for us to grapple with an idolatry of justice. As technology affords us both an instantaneous and relentless awareness of myriad justice causes, and the often-illusory perception of our capability to effect change, it becomes very easy to puff up our justice egos and enlarge our savior complex. Pragmatism and good ol’ work ethic drives us to advance our movements by documenting success, hitting program goals, and mining visible storytelling of dramatic life changes of the people we rescue.

Imagine what it would look like for a diverse mosaic of justice movements to stand together to oppose white supremacy.

Imagine what it would look like for our spirituality to be infused with a longing for repair and restoration of what centuries of racial division have broken.

Imagine what it would look like for a room full of business leaders, local pastors, grassroots organizers, and artists to discuss real answers to deep problems.

That’s the vision for The Summit 2016. And we need your help to make it happen.

Rape. Domestic Violence. Acid Burnings. Female Infanticide. Human Trafficking. Emotional Abuse. Sexual Harassment. Genital Mutilation. These are just a few forms of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) that women and girls endure on a daily basis. But these assaults on the human spirit and sacred worth of women and girls will not have the last word.

Black History Month is a time to reflect on the contributions African Americans have made to this country. We are right to pause and look back on those who have fought for justice and equal rights. But we mustn’t stop there. We also need to look forward and act to address one of the deadliest legacies of racial inequality: toxic pollution that is harming our children and poisoning our environment.

“When I see you, I don’t see color,” is something white women have said to me for decades. When heard from white women I see as sisters in Christ, these words erase me. For years I tried responding. I might say, “I get that you are refusing to attribute to me the bad things you have heard about people of color,” to which might come the response: “Oh no! I was raised to accept everyone!” Or I might say, “I know you mean that as a compliment,” and she might say, “I really mean it; I don’t see your color!”