I'm deputy web editor for Sojourners, where I report on culture, tech, and religion, and look for voices to contribute to conversations on faith, spirituality, justice, innovation, and daily life. A collection of my reporting on sexual abuse and Christian communities, "I Believe You: Sexual Violence and the Church," was published in 2014 (avail on Amazon).

Beyond the religion beat, I also write on business, tech, community innovation, nostalgia, loss, collective memory, and war, with work appearing in the Atlantic, Pacific Standard, the Washington Post, Think Progress, and Books & Culture. In 2014, I spoke on collaborative solutions and "Do It Together" design models at SXSW in Austin, Texas.

My favorite postures are ethnographer and producer — reporting on the spread of subcultures, ideas, objects, and beliefs through time and place; and creating the conditions for others' voices and talents to thrive.

My nonofficial, not-so-subtle goal is to keep D.C. weird. Hold me to it.

Posts By This Author

The Aesthetics of Joy

Joyful design has the ability to provoke the public conscience.

IN MY FIRST week of design school, I found myself riding Austin’s notoriously limited public transit system, asking fellow riders why they used it, what would encourage them to ride more often, and what they would change about the service.

After a handful of interviews, my rides yielded an unexpected insight: Users didn’t like Capital Metro’s expanded hours and new bus routes. The changes, implemented in June, were ostensibly for the riders’ benefit. But people’s routine included a strong aversion to change. And for a population already dealing with a rapid rate of change in their city, the new routes were especially disorienting.

Any externally forced change can represent an existential threat—as we know all too well from our daily news cycles. Even something as small as the sudden restructuring of our—or our kids’—commute can throw our perceptions of relational, financial, or political safety into jeopardy.

We’re in a wearying time. And looking at CapMetro users’ responses, I began to wonder whether we can build levity into a daily commute as a form of comfort blanket for these users. How can we offer delight as an antidote to people who are really, really weary of change?

Design and the Pursuit of Justice

Human-centered design can be a revolutionary pathway to social justice.

DEBATE THE CHOICE all you want, but what was radical about a congressional candidate’s ban on press at an August public town hall event wasn’t her decision to shut out journalists. It was how publicly she was willing to attempt new things, to try to make democracy work for a new slice of participants.

“We are genuinely trying to create environments where our constituents feel comfortable expressing honestly and engaging in our discourse,” she tweeted. “Genuine Q?: how should we label a free campaign event, open to all, that’s a sanctuary space?”

Though she and other justice-minded public officials may not use these words, what they are attempting is a kind of human-centered design.

Human-centered design is fairly self-explanatory: When designing systems, services, or products, creators place humans at the center. But in practice, this can be radical: If my focus is to make an experience better for each user, I will design for individuals, not market trends; I will design for the outliers and anomalies, not the majority.

And, critically, it requires empathy, using every tool I can muster to fully understand what the user experiences as they interact with the system, solving problems worth solving.

Of course, the best way to learn the process is to go through it yourself.

Designer Antionette Carroll lives in Ferguson, Mo. After Mike Brown was killed in Ferguson, she asked herself, “What should designers do?”

For Viewers, It's Virtual Reality. For Immigrants, It's Life.

Filmmaker Alejandro Iñárritu's newest project, "Carne y Arena," plunges visitors into migrants' trauma.

PRE-EXPERIENCE: Welcome! You’re alone except for a receptionist, who gently asks you to sign a waiver and gestures to the couch. The sand-colored cushions perfectly complement the soft pink glow of the wall and a pot of shellacked succulents. The coffee is pleasantly warm. The room temperature is perfect. Everything is fine.

You’re here for “Carne y Arena,” a virtual reality experience created by Mexican filmmaker Alejandro G. Iñárritu. The project recreates the experiences of immigrants who cross the Mexico-U.S. border. In 2017, “Carne y Arena” (“Flesh and Sand”) won a Special Award Oscar, the first given for virtual reality. The exhibit accommodates only one visitor at a time, at 15-minute intervals.

You wait on the couch, feeling a twinge of anxiety over an immersive experience that requires isolation and allows no cameras or notebooks. You contemplate the Pinterest-nirvana of the lobby and scratch a few notes while you can.

Entry: So where are we, exactly?

Soon, you’re escorted through the doors of the exhibit, which is housed in an old Baptist church in a gentrifying neighborhood in Washington, D.C. The project will take place across three rooms, a triptych of the migrant experience.

The church was slated for demolition before “Carne y Arena.” On the way in, you pass walls that look strangely familiar—you’ll later realize they are repurposed fence panels from the U.S.-Mexico border, turned horizontal to fit the dimensions of the house of God. You’re pretty sure that works as a metaphor, but before you can chew on it, you’re inside.

You're Not That Special, and Other Lessons from Kate Bowler

An Interview with 'Everything Happens' Author Kate Bowler

"I think honestly, the hardest one is that I thought I was special. I thought there was something special about me that would prevent the worst possible thing from happening. I don't know where that came from, if it's just the hubris of living and that we can't imagine ourselves dying at all. But I think I really thought I was special."

Bodily Prayer

God has placed eternity in the fleshy, beating hearts of humans.

NOTHING MAKES SENSE in the desert. Rocks that should be rock-colored sprout purple and pink under an impossibly blue sky. Barren cacti produce new blossoms. A wintry shade blisters in the sun. Canyon stone, having survived a billion years of harsh wind and water, crumbles in a human hand.

In a time when technology increasingly serves to nullify our bodies, the desert’s physicality obliterates the mind.

I’ve come to the Grand Canyon to remember that I still have a body, pitching camp in one of the last places on Earth where wireless data won’t reach. Simone Weil writes that prayer is an act of paying attention, and in the absence of overactive phone-brain, I’ll be sleeping outside for a week, listening to rivers and silence, kayaking along canyons, hiking through severe elevation, relying on basic survival instincts.

Poetic Justice?

The moral of the story? We're working on it.

Everett - Art / Shutterstock

YOU HAVE TO feel for Dean Kamen, inventor of the Segway, who probably gets tired of hearing about his own death.

Kamen, still very much alive, introduced the self-balancing vehicle in 2001. But since 2010, when new Segway Inc. owner Jimi Heselden accidentally drove a Segway off a cliff to his death, popular memory has conflated the tragedy with its creator.

There are any number of plausible reasons for this case of false identification, but one of the most persistent deals with moral comeuppance: A person invents an obnoxious, silly vehicle; a person dies from the frivolous invention. It isn’t kind, but that sort of morality tale is enduringly satisfying. When we despair for humanity, our inner cynic appreciates when humanity gets what’s coming.

Kamen isn’t the first victim of misapplied poetic justice—fascination with the archetype of the doomed inventor stretches back to Greek myth, punctuated by names from Hamlet (whose snide “’tis the sport to have the engineer / hoist with his own petard” unwittingly championed his impending demise) to Alfred Nobel, who, despite popular myth, did not actually have many regrets about inventing dynamite.

John Sylvan, inventor of the Keurig single-cup coffee dispenser, is a recent case of the regretful kind—he publicly laments having introduced the waste-belching quick-fix to bulk coffee, and later designed a fully recyclable prototype that would remedy the environmental concern. But most of us only know (or care?) about that first part.

There’s something viscerally satisfying in the demise of a technological Icarus. Such falls let us root for our own inertia—a triumph against the hubris of building something nonessential, and the idealism of thinking it could change the world. To stop at a moral tale of disaster is to keep the focus on poetic justice and our own wisdom. It also, conveniently, keeps us from having to face the complexity of, “What do we do about it now?”

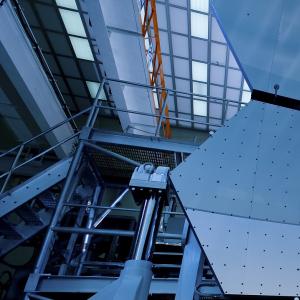

The Heartbeat of Deep Space

In our science narratives, there’s a long tradition of featuring beautiful, rich white people and ignoring people of color and women.

Mirrors on the James Webb Space Telescope / Credit: NASA/MSFC/David Higginbotham/Emmett Given

THE FIRST THING NASA cinematographer Nasreen Alkhateeb does when approaching new stories is to look for the heartbeat. A transmedia artist, Alkhateeb spent much of the last year at NASA recording Goddard engineers as they constructed the massive James Webb Space Telescope, set to launch in 2018. The largest-ever space-based telescope is designed to capture images at an astonishing distance, collecting data on the formation of some of the first galaxies in the universe.

Alkhateeb’s job, she says, was to translate the complexities of this tool to a non-science audience. For that, she primarily focused on the workers on the ground.

“It’s really about all the different fingerprints that have touched this project,” she tells me. “The story of the telescope goes hand in hand with telling the story of the individuals and the agencies who are collaborating to build it.”

Outer space has twinkled in the American imagination at least since since NASA’s founding in 1958. One secular hope for salvation lies in inhabiting the heavens—whether on Mars, a source of fascination for National Geographic and for SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, or elsewhere.

Yet the role NASA will play in future space exploration is up for debate. Public faith in NASA is strong—the agency is the second most-trusted government institution in America, after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The new Trump administration “clearly values space as an inspirational tool,” Pacific Standard opines. But there’s quite a bit to suggest a reshuffling of funding priorities from the president, whose advisers have challenged NASA’s focus on earth science—including recording the evidence and effects of climate change, which will disproportionately affect poor and marginalized communities.

The World Begins Anew

To see blooms adorning a church on Ash Wednesday—instead of at Easter—scrambles the spiritual metaphor.

REMEMBER THAT you are dust, and to dust you shall return. The prayer said around the world on Ash Wednesday wielded a rather pointed moral to the tail end of the hottest February on record where I live. Penitents in my neighborhood church shuffled in a sun-kissed line to receive ashes on tanned foreheads, summer sandals slapping the floor. Outside, overeager daffodils bloomed their Easter welcome. A strange one, this backward Lent: balmy with a side of dread.

This existential reversal felt nothing if not timely—all through the winter, a collective litany of weary newsfeeds asked whether we really needed quite so much of it. The first months of this year have witnessed a steady erosion of trust in whatever institutions we had left: the federal government, the electoral process, our checks and balances, our freedoms, our faith, each other. Some trace our hard skid sideways to the election, or the Super Bowl, or the Oscars. (I peg it to the Cubs’ win in November. I grew up in Chicagoland—I know reversing a curse has consequences.)

But there’s something particularly dizzying about the separation of church and earth. The globe is getting hotter every year now, but the effects of this ecological trauma, like any grief, are far from linear. If warming simply meant the usual weather, shifted a month early or late, we could figure out how to recalibrate—but our snowfall is breaking records and our ice caps are melting. A winter afternoon can begin as warm as an early summer day and suddenly drop 25 degrees to freezing rain.

Entering My 'Power Decade'

My over-30 colleagues have shared a common sentiment: Our 30s are so much better than our 20s.

IT IS A TRUTH universally acknowledged that a woman turning 30 must be in fear of her age. When I was 27, I got an accelerated peek into the process—I was in a bad car accident, and the recovery left me temporarily reliant on the trappings of old age: breathing apparatuses, a mostly liquid diet, walking with a cane.

I managed to weather it with good humor, knowing most of the changes were temporary (who hasn’t dreamt of shaking her cane from a porch at noisy youths below?). Now, back in my “correct” age, I’m grateful for that behind-the-scenes trial run at the other end of things. To be young and healthy again is a relief. But I’m now not afraid of aging, either.

I turn 30 this month. To be, at 30, unmarried, childless, career still evolving, and happy about it, as I am, is still viewed with suspicion, especially for women. While we’ve mostly divorced specific ages from expected signifiers of “adulthood”—marriage, children, home ownership, defined career—there’s still an underlying social expectation for women and men alike: Your 30s are when you “settle down.”

But my brief sojourn into old age didn’t give me a craving for these trappings of thirtydom. Instead, this visit to the end of the line gave me a deep look into my own soul. I did not emerge from enforced solitude in my later 20s looking to lock down a career and a man. I did emerge eager to honor my soul’s boundaries, newly curious about the divine, insistently pulled toward creating spaces of peace and healing for others.

Now that the chronological experience of life has been scrambled and the expected scripts tossed out, crossing over into 30 feels like the beginning of some real fun.

Radical Refuge

The Sanctuaries collective creates a new kind of sacred space for art and justice.

Image via The Sanctuaries Facebook

I.

My family was earthquaked

I changed the noun into a verb

because it’s almost like someone did this to me on purpose ...

—Sanctuaries artist Mazaré, “Where is God in the Natural Disaster?”

OUTSIDE, A MID-NOVEMBER storm of biblical proportions is raging, but the hushed crowd gathered in this church basement is in rapt attention to a woman giving testimony. In the parking lot, a hollowed-out school bus holds the detritus of a homeless life. A handmade “Wheel of Misfortune” dangles from one rain-splattered window, over empty bottles and voided bank notes.

Suddenly the crowd erupts in cheers, and the poet, grinning, cedes the floor to a pair of musicians. Today the church is playing host to a collaboration between Street Sense, a publication run by and for Washington, D.C.’s homeless community, and The Sanctuaries, a D.C.-based art, spirituality, and justice collective. The bus—filled with real experiences of D.C.’s homeless community, represented by Sanctuaries artists—will tour the city as a mobile story. It’s the culmination of months of work. To some, it’s an act of resistance. To others, it’s church.

For all the breathless predictions of what the day after Nov. 8 might bring, a reckoning with mortality was not one of them. Yet a marked grief snaked across some newsfeeds and private emails in the days that followed—a feeling that with the election, something precious about life as we knew it had died.

That morning, the founding organizer of The Sanctuaries, Erik Martinez Resly, sent a simple note to members: “I love you.” A few improvised hours later, a small group had huddled at a church on 16th Street in D.C. to share the real-time experience of the country’s historic change in direction. For The Sanctuaries, response looked like art and togetherness—two qualities that have guided the group from its beginning.

Maybe We've Gotten Gratitude All Wrong

An Interview with 'Grateful' Author Diana Butler Bass

Woodiwiss: We're coming up on Good Friday and Easter. And a lot of strains of Christianity teach the story of Good Friday as, “God also gave us this gift of Jesus’ death. It was horrible, but Jesus did it to pay for our sins, so we have to worship him.” There's this implied debt.

Bass: It makes absolutely no theological moral or biblical sense at all. So where do we get that? It's very complicated, but Protestantism was built on this idea of faith: On one hand, they said that salvation was a free gift, that it was the act of grace. On the other hand, they complicated that free gift with this idea of economic exchange.

Note From Self

Along with nostalgia, Facebook delivers daily reminders that we haven't always been correct...or cool.

RECENTLY, a Facebook troll accused me of liking country singer Carrie Underwood. The troll was ... me.

“I hate to admit it ... but in the interest of full disclosure, I kind of love Carrie Underwood’s ‘Cowboy Casanova,’” said 23-year-old me. Real-time me was horrified.

The indignities kept coming. College junior me: “I was impressed by Mike Huckabee and Ron Paul,” after a GOP debate in South Carolina in 2008. ( Mike Huckabee?!) College senior me, more inscrutably, presumably comparing President Obama’s first inauguration to Woodstock: “Back from Obamastock, living the dream.”

Of all the ways to be internet shamed, I hadn’t counted on my old selves.

Launched in March 2015, Facebook’s feature On This Day collects every status update and photo users have shared on that day, every year, all the way back to the beginning of (Facebook) time.

For a social platform, this function is oddly, endearingly private. Newsfeed and Pages and Groups are where we meet others, but On This Day is where we meet ourselves. The for-your-eyes-only digital diary delivers a daily string of our admissions from years gone by, betting on our appetite for nostalgia and navel-gazing. Sometimes, reading the morning roundup delivers an ego boost. (“I was funny!” I once announced to an empty home.) Other times, I’ve shared things that my present self flat-out refuses to believe.

Facebook is 12 years old and has been with me longer than most close friendships in my life. And it acts like it: On This Day is a best friend eager to remind me how desperately, and how often, I’ve tried to be cool. But it also reflects me at my most earnest, filled with unselfconscious observations on life and tentative explorations into new ideas of justice, identity, and belonging.

2018 World Watch List: Christian Persecution Rising, Women Particularly Vulnerable

Open Doors USA, a ministry that works with persecuted Christians around the world, released its 25th annual World Watch List at the National Press Club Wednesday in Washington, D.C. The list, a compilation of field interviews and aggregated data from other agencies, ranks the 50 most dangerous countries in the world for Christians. Dangers include religious militancy, organized corruption, Islamic extremism, among other factors.

The Day That Had Two Noons

"Does a clock have anything to do with religion?"

AS FAR AS WE know, Nov. 18, 1883, was the only day in history to have two noons. In a move to standardize haphazard railroad timetables, the United States was divided into time zones. Major cities wound their clocks to a newly designated “noon,” suddenly separated from their neighbors into zones of “now” and “not yet.”

Some newspapers and bulletins responded with humor. “We were not so far behind as [Maine], and therefore do not need so great an advance,” one Trenton, N.J. paper joked.

But this existentially momentous event was largely observed with pragmatism. “When the reader of THE TIMES consults his paper at 8 o’clock this morning at his breakfast table it will be ... 6 o’clock in Denver, Col. and 5 o’clock in San Francisco. That is the whole story in a nut-shell,” declared The New York Times. The slight change was necessary for standardization—time zones meant progress, efficiency, growth. Who could argue?

And so there was noon, and there was noon again, on that first day.

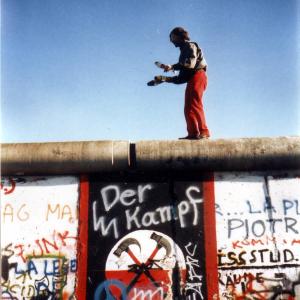

The Mistake That Toppled the Berlin Wall

While much destruction can come from human error, small mistakes can sometimes course-correct for good.

The wall wasn’t supposed to come down.

Günter Schabowski, a spokesperson for the East German Politburo, was tired. He hadn’t thoroughly read the travel regulation updates, handed to him shortly before his news conference. He didn’t know the document’s shifts in rhetoric, developed by leaders in the East German government, were simply an attempt to appease the swelling ranks of East Germans demanding reform. On Nov. 9, 1989, facing journalists’ cameras and notepads, Schabowski took questions for a forgettable almost-hour. Then someone asked about rumors the border may open.

Schabowski mumbled over his answer, confused. But a few of his words were clear: “Immediately ... right away.”

Reporters pounced. Breathless reports in West German media soon filtered over the wall through East Germans’ pirated signals. The Politburo had assured checkpoint guards that no changes had been made, but it was too late—a trickle of curious East Berliners quickly grew to massive crowds, yelling “Open the gate!” At a loss, and unable to get through to leadership for clarification or backup, the guards eventually gave in. Within hours, nearly 40 years of iron-fisted East-West divide was undone.

What Should You Do When Your Church Does Not Condemn Hatred?

"Maybe what surprises me most is how widely the hashtag resonates. I couldn't have anticipated it going this viral. And it's been interesting to see ex-Mormons and ex-Catholics chiming in as well, and in a few cases former ultra Orthodox Jews. As far as I'm concerned, #EmptyThePews is for anyone who finds value in it."

When the Resistance Isn’t Sexy

We dream of a sensational fight, but have little appreciation for the mundanities of evil.

Greger Ravik / Flikr.com

THE BROKEN MEN of Prague lurch down Petřín hill toward Malá Strana, their hunger as clear as the hollow iron torsos where their bellies used to be. The man leading the march looks whole, more or less, but visitors can see his followers slowly dissolve behind him ... a gash here, a missing arm there, until, at the top of the stairs, only a foot where a whole man used to be.

To capture a human in the process of breaking apart requires attention. It’s immediately clear that the sculptor of these Broken Men, Olbram Zoubek, was intimately familiar with the process. Prague’s Soviet occupiers also knew something about decay, which the monument commemorates with grim precision—at the feet of the statues is a thin bronze line marking the numbers of Czechs affected by Soviet-era communism: 170,938 forced into exile ... 327 shot trying to escape ... 4,500 dead in prison. But the numbers are but a footnote to the decaying bodies on the hill. The long, grinding erosion of civil society is a personal trauma all its own.

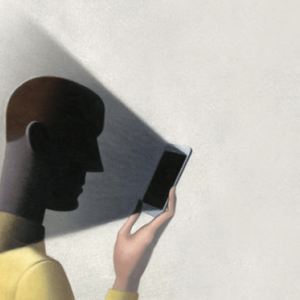

How Do We Avoid Becoming Numb in the Face of Online Tragedy and Violence?

The world hurts everywhere, including in our social media feeds.

IF THERE IS ONE CONFESSION a journalist never wants to make, it’s that she can’t handle the truth. Many of us got into the business for the express purpose of truth-telling, and for journalists growing up in the post-9/11 dawn of the 24-hour news cycle and the war in Iraq, the challenge to tell it boldly and well is our guiding star.

The nights are awfully cloudy these days.

When Syrian refugee children washed ashore in Libya in 2015, the images were indelible in their lonely, awful stillness—our decade’s “vulture and the little girl,” our “Falling Man.” Editorial rooms around the country debated whether splashing images of drowned babies across our platforms was truly in the public interest. Can pressing on exposed nerves yield anything but a howl?

Many outlets—including Sojourners—decided against publishing the photos. Everyone saw them on social media anyway.

White Women and Racial Complicity

How do we face being precariously power-adjacent?

WHEN WATCHING a creative imagining of what feels like your own demise, the last thing you want is for an audience to cheer. But for white women watching Get Out, the record-breaking horror flick from comedy writer Jordan Peele, that’s more or less what happened. It was a revealing moment, to say the least.

Get Out follows black photojournalist Chris, whose white girlfriend Rose invites him home for a weekend. To his terror, Chris slowly realizes that her nice, white, liberal family is masking a deep, violent racism. (“I would have voted for Obama for a third term” is a catchphrase played first as proof of the family’s “colorblindness” and later revealed to be a cover for their fetishization of black bodies.) Rose—a seemingly “woke” white woman, who yells at cops for unfairly profiling her black boyfriend—is, without giving too much away, a less-than-ideal ally.

The film was released one month after Trump’s inauguration, and it was easy to cheer for Chris as he took ownership of his fate and sought vengeance on his captors. In the last year, we’d seen unabashed patriarchal white supremacy pulling the levers in our politics and our churches. But then 52 percent of white women—many of them white Christian women—voted for Trump, and the role of white women in building and perpetuating damaging policies, narratives, and theologies was made more clear. Frankly, for me, and other white women who raced to see the film, Get Out felt like a chance to atone. White women have often skated by in the larger battles over identity and justice, inside and outside the church: Let us now give our money to the telling of truth.

To be a white woman in America is to be precariously power-adjacent: Because of our skin, we carry unquestioned privilege in power systems. Because of our gender, that security has a shelf life—we are included only as long as we are able or willing to perform according to those who control the levers.

60 Congregations in DC Metro Area Pledge to Provide Sanctuary

"People have asked, 'Why do you stand with these people?' Because black bodies have been assaulted since we first came to this state. And they are continuously assaulted. What we know is, if we are silent when brown bodies are assualted, when gay bodies are assaulted, when trans bodies are assualted, when female bodies are assualted, then all of us remain in prison and in bondage."