Culture

We lost a funny man on Monday to a sad and persistent disease. Robin Williams passed away last night of an apparent suicide.

In memory of Williams, we've compiled a few of our favorite scenes.

1. Aladdin

Williams' performance as the lovable Genie: "Ten thousand years will give you such a crick in the neck!"

This Friday, a movie version of the classic novel “The Giver” opens in theaters with an impressive cast, including Oscar winners Meryl Streep and Jeff Bridges. “The Giver,” originally written by Lois Lowry, explores a seemingly perfect world where all conflicts have been resolved and annoyances — such as bad weather and adolescent “stirrings” — have been eradicated, allowing this culture to achieve a beautiful state of “sameness.”

As you can imagine, this utopian society is not so utopian. “The Giver” focuses on young Jonas, who has been selected for a daunting task: to serve as society’s sole proprietor of memory and emotion. Jonas learns about pain and sadness, but also experiences beautiful colors, a thrilling sleigh ride and ultimately learns to feel love. In other words, Jonas learns what it means to be human — and that his world may not be so perfect after all.

“The Giver” is the latest in a wave of dystopian stories that have washed over America in recent years. From this summer’s “Purge” sequel and “Under the Dome” to the latest “Hunger Games” movie (due out in November), people can’t get enough of these apocalyptic fantasies, in which seemingly perfect worlds turn horrific.

Why such an appetite for dystopian stories now?

During his 1930-31 fellowship at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer joined his African American classmate Albert Fisher as a regular attendee at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem.

WHEN BONHOEFFER entered Harlem with Fisher, he met a counternarrative to the white racist fiction of black subhumanity. The New Negro movement radically redefined the public and private characterization of black people. A seminal moment in African American history had arrived, and all of Bonhoeffer’s descriptions of his involvement in African American life during his Sloane Fellowship year occurred during this critical movement. He turned 25 that February. Bonhoeffer was experiencing that critical moment in African American history while he was still young and impressionable.

The New Negro, a book containing a collection of essays, was edited by one of the leading intellectual architects of the movement, Alain Locke. The New Negro, as Locke and his authors appropriated the term, described the embrace of a contradictory, assertive black self-image in Harlem to deflect the negative, dehumanizing historical depictions of black people. The New Negro made demands, not concessions: “demands for a new social order, demands that blacks fight back against terror and violence, demands that blacks reconsider new notions of beauty, demands that Africa be freed from the bonds of imperialism.” Bonhoeffer knew the movement by the descriptor New Negro, but James Weldon Johnson preferred to describe the movement as the Harlem Renaissance ... as a rebirth of black people rather than something completely new. ...

HERE’S WHAT Slow Church is not: A how-to manual with five easy steps to make your congregation more thoughtful. A celebration of how using the word “community” often on your church website will multiply your pledge and attendance numbers. An ode to really, really long worship services.

Rather, Slow Church explores being church in a way that emphasizes deep engagement in local people and places, quality over quantity, and in all things taking the long view—understanding individuals and congregations as participants in the unfolding drama of all creation. Authors C. Christopher Smith and John Pattison are self-proclaimed “amateurs,” insofar as they are writers-editors and lay leaders, not professional pastors, theologians, or congregational consultants. But this book is richly informed by their experience in their own church contexts (Englewood Christian Church in a gritty neighborhood in Indianapolis for Smith; an evangelical Quaker meeting in small-town Oregon for Pattison), conversations with other church communities, and close reading of classic and contemporary literature on culture, Christian community, scripture, and spirituality

THE KENNAN DIARIES, carefully edited by Frank Costigliola, a University of Connecticut historian, covers an amazing and sometimes disturbing 88-year period of personal journal-writing by George F. Kennan, who became the most famous diplomat-intellectual of the 20th century.

Born in 1904 (he died in 2005) Kennan, a Milwaukee native, grew up in an upper-class Scotch-Irish Presbyterian family with three older sisters and a father who was a tax attorney.

After graduating from Princeton, Kennan became a Foreign Service officer with the State Department, eventually serving in posts throughout Europe. But Kennan’s first love was Russia. He wrote in his diary that “he had a mystical connection to Leningrad, as though he had once lived there.” He was offered a three-year university stint in Berlin by the State Department—Kennan’s boss wanted him to be educated like a pre-Bolshevik Russian gentleman. Kennan’s grasp of the Russian language and history became exceptional. Together with his prodigious analytical skills, it would be the foundation of his brilliant career.

After 20 years abroad, Kennan fired off his famous 5,540-word “Long Telegram” on Feb. 22, 1946, from Moscow to Washington. Soon afterward, in July 1947, he wrote another piece in Foreign Affairs under the byline “X.” In the two pieces he said that the Soviets under Stalin would try aggressively to expand, but that the U.S. should not employ military means to stop them. Instead, Kennan advocated “containment,” heavily monitoring the Russians with hard-headed diplomacy and tough talk. He also stated that the Soviet Union would eventually self-destruct.

WHAT’S A GOOD priest for? So asks Calvary, the second feature film from writer-director John Michael McDonagh, rooting itself in Ireland’s coastal landscape, centering on a pastor threatened with scapegoat-retributive murder from a grievously sinned-against parishioner. Its vibe owes a great deal to the quiet reflection of films such as Jesus of Montreal and Au Hasard Balthazar (in which a donkey evokes the love and wounds of Christ), and the archetypal Westerns High Noon and Unforgiven. Brendan Gleeson plays a priest who was drawn into the church after his wife’s death, which allows us the rare experience of seeing a cinematic Catholic priest who is both a parent to his flock and to a beloved daughter, who feels somewhat abandoned by his commitment to the church.

Gleeson has the uncanny ability to hold his massive frame as both solid—almost concrete—and vulnerable. Knowing that everyone is both broken and breaker, his Father James is healing on behalf of a flawed institution, although he doesn’t confuse vocation with a job. His bishop’s response to a request for help is “I’m not saying anything,” reminding me of Daniel Berrigan’s challenge to religious hierarchies, heard at a public meeting in Dublin in the run-up to the Iraq war: “In Vietnam, they had nothing to say, and said nothing; now, they have nothing to say, and they’re saying it.”

Father James understands the difference between stewarding power and grabbing it (one obvious signal of his goodness), and he is up to his neck in the community, running the gamut from friendship with an American writer looking for inspiration in the land of his presumed ancestors to a visit with a former pupil whose own inner darkness has led him to do monstrous things.

Church Makers

In Accidental Theologians: Four Women Who Shaped Christianity, Elizabeth A. Dreyer delves into the theology of four female saints of the Catholic Church, Hildegard of Bingen, Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Avila, and Thérèse of Lisieux, describing their impact on the church in their times and today. Franciscan Media

Global Feast

The revised edition of Extending the Table cookbook (first released in 1991) includes new dishes, regional menus, and more photos, as well as prayers and stories. It is part of the World Community Cookbook series commissioned by Mennonite Central Committee, and royalties support MCC’s work. Herald Press

PRIOR TO MY conversion to Christianity, I was the roving reggae reporter for High Times, a magazine dedicated to marijuana culture. I also wrote music reviews for NY Press, Virgin Records, and various other publications.

One of my favorite artists from the early 2000s was Cody Chesnutt (he spells his name with two capital Ts at the end), an independent recording artist popularly known for his hit song “Seed 2.0,” a soulful rock and hip-hop hybrid released in 2002 with The Roots.

Chesnutt’s musical debut was a lo-fi soul and rock-and-roll album titled The Headphone Masterpiece. It was a double disc (this was still the heyday of compact discs) that he recorded on a 4-track recorder in the bedroom of his Los Angeles apartment. He played all the instruments—guitar, bass, keyboard, and organ. The sound quality and lyrical content are both intentionally gritty.

Headphone quickly became the soundtrack to my college years. I was a reveler, filled with hypersexual bravado and abundant egotism, and Chesnutt’s music reinforced and undergirded my misdirected youthful zeal. His lyrics were unrepentantly misogynistic, and his strong sense of self pervaded each track. He exploited his infidelity and womanizing in his music, at times in a prophetic way, such as in “My Women, My Guitars,” which he opens with incredibly crude lyrics, but later croons with utmost vulnerability: “Man, something’s been killing me. My women, my guitars. I’ve been living hard. My breakdown is on the way. I know my breakdown is on the way. So I get up on my feet. Falling back on my knees to pray.”

No abundant bright bloom of flowers on the CD cover or obscure Latin in the title or gentle dance of cursive font describing the song list, nothing can hide that this is not your light-and-breezy summer release of cruising-with-the-top-down jams, but rather, a full-blown concept album of folk hymns about the art of dying.

The Art of Dying (officially Ars Moriendi) represents a brave and risky move for the make-it or break-it breakout album of an up-and-coming band. The Collection’s courageous collection of orchestral pop hymns chart and curate the grieving heart of a gifted songwriter and the community of bandmates and fans that surround him.

At a time when the flame of the alternative folk explosion still burns bright despite much backlash, this North Carolina ensemble shows up as the son of Mumford and Sons, married to Edward Sharpe’s second cousin, with too many members to pack the tiny stages of clubs and bars, with a sound fit for mountaintop vistas, and songs as mystic visions that pierce the veil between life and death.

Despite the heavy earnestness of the entire package, it’s exactly the grief-support-group that my ears need, and I imagine a rendering of fragile faith and hope against hope that our world craves. The Collection manage to sing about Jesus and Thomas and the prodigal son without getting pushy, dancing on the fringe of explicit CCM, exploring sacred-meets-secular crossover paths and gritty crossroads that groups like Needtobreathe, Drew Holcomb and the Neighbors, and Gungor have already traveled.

Death remains that earthly finality to render our denial mute — and our religious musings about whether it represents cosmic reunion, bodily resurrection, or eternal rest are powerless when we admit that the mysterious premonitions of the “heaven is real” crowd are but passing glimpses and not bulletproof facts. The Christians that remain relevant in our world have invested in the Kingdom here, now, and all around us, and they don’t shove tracts that guarantee afterlife fantasies in our faces on the same street corners where tramps and hobos sleep and sometimes starve.

There’s never a better time for a bunch of holy avengers than when all hell actually breaks loose.

The Dynamite Entertainment series The Devilers debuts Wednesday as an action-packed supernatural comic book full of demonic beasties, big-picture philosophies, and heroes that have to put religious differences aside in order to save Vatican City – and the world – from being turned into brimstone.

“When suddenly it’s ‘Oh that is a giant hellmouth that opened up in front of me,’ that changes your beliefs,” said series writer Joshua Hale Fialkov (The Bunker, The Life After), who’s doing the The Devilers alongside artist Matt Triano.

THROUGH THEIR EYES

In 2011, Raul Guerrero provided 100 Kodak disposable cameras and taught basic photography skills to nine young students in the Newlands area of Moshi, Tanzania. The Disposable Project book brings together their images of their community, with text by Guerrero. the-disposable-project.com

JOURNEYING

“Migration has been, for centuries, not only a source of controversy but a source of blessing,” Deirdre Cornell writes in Jesus Was a Migrant. Inspired by ministering among immigrants in different settings, this is a beautifully written set of deeply humanizing reflections on the immigrant experience and Christian spirituality. Orbis Books

AMID WORRIES about a new Cold War, of standoffs with old enemies and confrontations with new ones, Harvard professor Elaine Scarry’s latest book is a chilling reminder of the doom our presidentially controlled nuclear arsenal can unleash upon the world. Early on, she reminds us that President Nixon told reporters, “I can get on the telephone and in 25 minutes 70 million people will be dead.”

This boast illustrates Scarry’s thesis: We live in a thermonuclear monarchy, where one person—the U.S. president—can destroy the world. Nuclear doom is an accident waiting to happen, and she reviews a number of barely publicized near misses.

But she sees a solution at hand—the U.S. Constitution, specifically both Article I, Section 8, which says that Congress alone can declare war, and the Second Amendment. The text of the latter reads: “A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” (Emphasis added.) Scarry argues that the amendment mandates a second level of citizen consent to war, a further brake to executive power, even after Congress has given its approval—that the writers of the Constitution intended that before the U.S. engaged in any war the people would have to consent to join a militia, a form of collective participation in the decision for war. According to Scarry, our out-of-ratio nuclear weapons stockpile, ready to launch at the command of a single person, has negated the Constitution-mandated chain of accountability and decision-making and is therefore illegal.

FAITH-ROOTED Organizing: Mobilizing the Church in Service to the World outlines a theological cartography of social change. In this critical intervention, Alexia Salvatierra and Peter Heltzel reimagine—and as a necessary consequence, rechart—the landscape of vision, action, and strategic planning needed for social change.

Full disclosure: I have attended several trainings conducted by the co-authors. Indeed, the dual authorship of the text is a principal strength. Faith-Rooted Organizing blends the voice of an evangelical-activist theologian in Heltzel with the homespun profundity of a seasoned pastor and campaign organizer in Salvatierra. The authors delight readers with complementary writing styles: Heltzel speaks through theological propositions, interpolated intermittently with jazz references and theological punch lines; Salvatierra communicates through proverbs, organizing anecdotes, poignant biblical passages, and narrative side notes.

The result is a well-argued and accessible text that should resonate from the seminary to the sanctuary. Their driving thesis is that faith communities, especially Christian ones, should organize for social change in a way that is rooted and guided by the stories, symbols, sayings, and scriptures of our faith. Faith-Rooted Organizing functions as an instruction manual on effective advocacy while providing a theological rationale and vocabulary for a vocation marked by tremendous victories and colossal failures, breakthrough partnerships and fragmented coalitions, glimpses of beloved community and portraits of democracy stillborn.

WHAT IS THE relationship between one’s religious beliefs and one’s economic and political views? Are some religious beliefs more “American” than others?

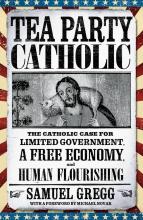

These questions come to mind in reading Samuel Gregg’s Tea Party Catholic: The Catholic Case for Limited Government, a Free Economy, and Human Flourishing. Gregg suggests that religion directly informs—or should inform—our understanding of political and economic issues and that religious, economic, and political liberty are inextricably bound. A perceived or real “attack” on one, he contends, is an attack on all.

Gregg is director of research for Acton Institute, a libertarian think tank whose core principles seek the “integrating [of] Judeo-Christian truths with free market principles.”

In Tea Party Catholic Gregg writes of a “new type of Catholic American” who is grounded in a “dynamic sense of orthodoxy” but whose “Americanness” is defined by faith in free market principles. Tea Party Catholic details how free market principles and a view of government “with clear but constrained economic functions” have, Gregg argues, not only deep roots in U.S. political history but also in Catholic tradition. Thereby, he suggests, any U.S. Catholic differing in his or her economic and political beliefs has neither a proper understanding of the United States’ founding nor of the teachings of the Catholic Church.

Gregg’s attempt to sacralize libertarianism is not consistent with Catholic doctrine: It runs counter to stated positions of the Vatican and the majority of Catholic theologians and economists. At a recent conference at The Catholic University of America one of Pope Francis’ advisers, Cardinal Oscar Rodríguez Maradiaga, said that in commenting on free market and libertarian influences on our global economy, Pope Francis gave a “sharp prophetic verdict: ‘This economy kills.’”

IT’S A TRUISM to say that television is outpacing cinema for entertainment quality and depth of exploration. Since The Wire appeared a decade ago, studios have been realizing that there is an audience for long-form storytelling that is willing to think.

Recently I’ve been struck by the set-in-the-’80s espionage thriller The Americans, the deeply haunting police procedural True Detective, the hilarious pathos of Louie and Veep, and the sly, shocking Hannibal, a prequel to The Silence of the Lambs: All hugely entertaining, dramatically credible, and challenging both as works that require sustained attention and in terms of what they say about life. The Americans is really an exploration of marriage and cultural identity wrapped up in Cold War cloaks-and-daggers; True Detective is a lament for the broken parts of America, and an affirmation that friendship endures above almost everything else; and Hannibal is a postmodern delving into Dante’s Inferno, looking at the underbelly of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s assertion that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

What’s most exciting is that it’s now considered viable to make drama that actually asks real questions about life and is prepared not to answer them pat. Along with the vast amount of social media conversation about these works, what we have is more akin to ancient forms of public entertainment that required a kind of audience participation—theatrical catharsis meeting gathered conversation to produce a community hermeneutic. When we talk about TV and cinema, we’re talking about ourselves.

THE CONTROVERSY over net neutrality has come back to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) where it began, and the commissioners need to hear, immediately, one simple message from ordinary citizens: “Reclassify broadband internet as a telecommunications service.”

You don’t really even need to know what those seven words mean. Just say them—by phone, email, fax, or carrier pigeon—until the commissioners get the idea.

That imperative sentence is aimed at preventing a policy shift that could turn our information superhighway into a fast, expensive toll road for the wealthy and force ordinary citizens onto a two-lane frontage road, with lots of traffic lights.

Net neutrality, as you may recall, is the principle that internet service providers—the companies that own the cable or the wireless frequencies that bring the internet to your device—should treat all digital content the same. Comcast shouldn’t block Amazon Prime to force you into its own video-on-demand service, and Verizon shouldn’t let Netflix pay more to get higher download speeds than its competitors. As a corollary, this means that independent filmmakers and video journalists have the same access to the online audience that the corporate big boys have.

WALTER WINK IS known as a lectionary commentator with lucid biblical insight, a chronicler of nonviolent practice, a scholarly essayist, an arrestee in direct action, and one of the most important theologians of the millennium’s turn. He effectively named “the domination system” and its collusive principalities, opened up biblical interpretation to an integrated worldview, and brought the New Testament language of power back on the map of Christian social ethics.

Two years ago he crossed over to God, joining the ancestors and saints. His first two posthumous books have now appeared. They make for good companion volumes. Let me weave back and forth between the two. Walter Wink: Collected Readings is the anthology of his core work. Just Jesus: My Struggle to Become Human is a short autobiography. The second is the more remarkable—because it’s so rare that a world-class scripture scholar should tell his or her own story in relation to encounters with the biblical witness. And all the more so because it was a project undertaken after he was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia.

Given the dementia, the book itself is an effort of his “struggle to become human.” An early version of the manuscript included oral history and other sources narratively adapted to a first-person voice, but in the end his partner in all things, June Keener Wink, pressed for it to be pure Walter. No words not his own. His voice is easily recognized in these pages, though not always in the familiar crafted and noted style, rich in quotable one-liners. The jewels are here all right, but this text feels simpler, sparer, plainer. There are prayers and memories of one suffering the weight and creep of memory loss. Though it is a book he conceived and set to writing, June (aided by a sainted editor) lovingly completed the sculpture with autobiographical pieces, journal entries, prayers, dreams, and important portions of his final magisterial work, The Human Being: Jesus and the Enigma of the Son of the Man. The latter, also well represented in Collected Readings, frames the struggle (Jesus’, Walter’s, and our own) to become human.

HBO’s “The Leftovers” is the feel-good series of the summer, if your summer revolves around root canals and recreational waterboarding.

Indeed, it’s pretty grim stuff — but quite engrossing and worth your time, thanks to intense performances by Justin Theroux and Christopher Eccleston, and the way creators Tom Perrotta, who wrote the book on which the series is based, and Damon Lindelof, best known for screwing up the end of “Lost,” unflinchingly tackle the nature of grief and the limits of faith.

Can you call it an apocalypse if you can still get a decent bagel afterwards? It’s three years after what has been termed the Sudden Departure, when 2 percent of the world’s population — Christians, Jews, Muslims, straight, gay, white, black, brown, and Gary Busey — suddenly disappeared.