Climate change

The climate is changing! Creation cries out!

Your people face flooding and fire and drought.

We see the great heat waves and storms at their worst.

We pray for the poor, Lord — for they suffer first.

WHO SHOULD CARE about the future? Young people, obviously, because they have to live in it. And they have done their job. I spent the ’80s and the ’90s and much of the ’00s listening to my peers complain about “kids today” and how they were apathetic and how it wasn’t like the ’60s and on and on. I don’t know if it was ever true, but it clearly hasn’t been in recent years: On issues from civil rights to prison reform to the one I know best—climate change—young people have been firmly in the forefront.

When I founded 350.org, the first iteration of a global climate movement, it was alongside seven college students—and it was their generation that built that movement out, from the divestment campaigners on college campuses to the Sunrise Movement that spurred the Green New Deal to Greta Thunberg and the many like her who built the powerhouse Fridays for Future coalition.

But they cannot do it alone. They need, in particular, their grandparents and great-grandparents—the boomers and the silent generation above them. Those of us in those categories are the fastest-growing demographic in the country—we add 10,000 to our ranks each day (though, of course, we subtract some too). We vote in huge numbers, and we have ended up with most of the assets, fairly or not.

FOR MANY OF us, this summer felt like a cosmic wake-up call about climate change. Fire, floods, hurricanes, and other cataclysmic signs of our rapidly heating planet seemed to offer near-apocalyptic warnings that we’re approaching a make-or-break point, especially for those already vulnerable because of poverty or geographic location. We almost didn’t need the scientists—such as those who produced the dire U.N. report in August—to once again sound the alarm, as they have done so many times over the past several decades, nature already having done the job in her impossible-to-ignore fashion.

Anger seems an apt response to global warming, given that the world’s climate crisis isn’t an unavoidable act of nature; rather, it’s rooted in intentional actions by people seeking power and wealth. The main perpetrators—including ExxonMobil and its GOP enablers—knew about the causes of climate change more than four decades ago and, as Scientific American put it, “spent millions to promote misinformation” and manipulate public opinion. Some might call such duplicity “crimes against humanity” and “indictable behavior.”

It’s not enough to carry bags of flour to those experiencing the impact of our actions. Our grief must play a part in generating climate-adaptive solutions for the most vulnerable now.

“SEBASTIAN FRANCISCO PEREZ was a 38-year-old farmworker working at a tree farm in Saint Paul, Ore. He had come here to gain some money for fertility treatments for his wife, because they really wanted to start a family. I guess people just weren’t aware of the signs of heat exhaustion and heat stroke. After some time, folks he was working alongside were like, ‘Hey, where’s Francisco?’ When they found him, he had passed away from the heat. When PCUN found out about that, we were outraged, because this was a very preventable death. We were openly advocating for the Oregon Occupational Safety and Health Division and the governor to issue emergency rules, because we knew something like this was going to happen. [After Perez’s death] we got these rules enacted. It’s important to have clean water, frequent breaks, and access to shaded areas, because when you’re in the field, there’s not really much cover.

AMONG THE MANY postures toward climate change, I am in the “alarmed” camp. I see indicators of a planet on the verge of widespread ecosystem collapse and want to sound the bells for everyone else to wake up and do something. Unfortunately, writes climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe, some of the ways we try to wake people up can have the opposite effect.

Saving Us expands on Hayhoe’s popular TED Talk on the most important thing you can do about climate change: talk about it. The book explores why piling on sobering facts and predictions can make someone dismissive about climate change even more antagonistic, and even make those who are concerned and alarmed check out in despair. Though Hayhoe includes plenty of climate science, what makes this book worth reading are the insights she shares from social science.

Religious leaders should stop saying things like, “We must be good stewards of Creation” or “Our faith teaches us to protect the Earth” and instead getting comfortable saying things like: “ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, and other oil and gas companies are systematically destroying the planet — and financial giants like JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, BlackRock, and Vanguard are bankrolling the destruction.”

This week, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a report on the state of the climate crisis. It is a report that frames, in the cautious language of science, the dire state of the world. This panel of experts from around the world found that warming of 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius in the next century is certain unless there are extreme and immediate cuts in greenhouse gases. This level of warming would spread and intensify the kinds of extreme weather — hurricanes, wildfires, floods, and heat waves — we have seen unfold for over a decade. This report shows us the reality that our actions will not be enough to prevent catastrophic climate change. Immediate action on climate can prevent the worst effects of climate change — but catastrophe has already happened. Catastrophes are happening all around us.

The United Nations panel on climate change told the world on Monday that global warming was dangerously close to being out of control – and that humans were “unequivocally” to blame.

Already, greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere are high enough to guarantee climate disruption for decades if not centuries, the report from the scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned.

Modernity claims humans are the only citizens — the owners and rulers of nature – thus fracturing our relationship with nature and with one another as we compete to amass or inherit resources. This voracious system is built to protect those with wealth and their resources rather than to protect human and natural life. The deadly consequences of this paradigm are evident: Last month, the United States experienced the hottest June on record since we began keeping track 127 years ago.

IT BEGINS IN the way the 2020s could end: with a climate change-driven heat wave that kills 20 million people in India. Kim Stanley Robinson’s work of science fiction is heavy on the science and light on the fiction. Indeed, the “fiction” of this novel reads more prophetic than futuristic. Just like biblical prophets, Robinson is less interested in predicting a far-off world than seeing our current world for what it is. The words of the prophet Jeremiah would fit snugly in this book: “Disaster overtakes disaster, the whole land is laid waste” (4:20).

Robinson’s vision of a response to climate change veers on the edge of technological utopianism without ever falling into the abyss. The airships, cryptocurrencies, and drones of Robinson’s novel are not simply fantastic simulations of a utopian (or dystopian) world. They are pragmatic responses to a world that is burning and melting under our feet. While the need for technological solutions is so apparent in Ministry (and in our own world), Robinson’s hope is not located in technology. Rather, the tentative hope of Ministry is found in the unwavering humanity of its many heroes.

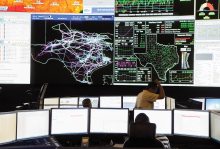

Texas ought to have a climate plan because that's the loving thing to do.

Hayhoe’s passion for climate science is based in her Christian faith. Hayhoe is an evangelical, which she defines as “someone who takes the Bible seriously.” For her, faith and science go hand in hand: The more that she learns about science, the more her “awe” and faith in God increases.

TRUMP IS BEHIND us now—four years of constant provocation and useless cruelty are over, which means ... we have about nine years left for the most important task any civilization has ever taken on. I want to lay out the basic math of our situation, because if we are at all serious about taking care of the earth God gave us (and we should be, since that was literally our first instruction), that math rules the day.

1) We are currently on a path to raise the temperature of the planet 3 degrees Celsius or more by century’s end. If we do that, we can’t have civilizations like the ones we’re used to—already, at barely more than 1 degree, wildfires and hurricanes have begun to strain our ability to respond.

2) In 2015, the world’s governments pledged in Paris to try and hold the rise in temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The United States, shamefully, exited that agreement for a time, but now we’re back in.

3) To meet that target, scientists say we need to cut emissions in half by 2030 and then go on cutting until, by 2050, we’ve stopped burning fossil fuel altogether. But the crucial year is not 2050. It’s 2030—if we haven’t made huge cuts by then, we’ll miss the chance to stop short of utter catastrophe.

On his first day as president, Joe Biden followed through on one of his pre-inaugural commitments: re-entering the United States into the Paris climate agreement.

Kyle Meyaard-Schaap is the national organizer and spokesperson for Young Evangelicals for Climate Action. He spoke with Sojourners' Jenna Barnett.

“IN 2017, Young Evangelicals for Climate Action marched in the People’s Climate March. [The next day] we invited God’s spirit to go with us into the halls of Congress. After we shared why climate change is important to us as young Christians, Sen. Mitch McConnell’s staffer asked, ‘How many of you identify as conservative or Republican?’ Nobody raised their hand. The staffer smiled, like he suspected this was a Trojan horse kind of deal where we were bringing young progressives in here and pretending like we were evangelicals. One by one the young people told the staffer how they had grown up in conservative Christian households and that many of them still held those values. But because the party had left them behind on climate change, they could no longer claim the party.

WHEN WE SAY that “humans are heating up the planet,” we are technically correct, and yet misleading. Humans are indubitably driving climate change—but only some of us.

An Oxfam study released this fall showed that between 1990 and 2015—a period when we poured more carbon into the atmosphere than in all of history before that time—the richest 1 percent of humanity accounted for more of that damage than the entire bottom 50 percent of the species. In case you think that the top 1 percent is Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, remind yourself that in fact it’s anyone whose income tops $109,000 a year—that includes plenty of readers of this magazine. The richest 10 percent of humanity accounts for half of total emissions—that’s everyone whose income is above $38,000. That’s quite likely you; it’s certainly me.

These people are scattered around the world, though the biggest concentrations are in the U.S., the EU, China, and the Middle East; India is appearing in the league tables too, a reminder that inequality is as much a problem within nations as between them. But what’s really sad, of course, is that anyone with a decent income is able to insulate themselves from most of the problems they’re causing. It’s people in poverty—whether in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans or along the delta of the Brahmaputra in Bangladesh—who get hit first and hardest.

Speculative futurism isn’t mentally escaping into a future that is either far more dystopic than our present or far more utopic than we should expect — nihilistically leaning into our sense of dread and doom, or engaging an escapist fantasy that all will be better someday and calling this ungrounded vision “hope” can both be momentarily comforting. A speculative futurist ecclesiology looks at every fault line exposed by this pandemic alongside every gift and grace it illuminates.

It’s the first time that a majority of Protestant pastors have according to a new survey by LifeWay Research.

The One Trillion Trees Initiative, launched by the World Economic Forum and led by led by the U.N. Environment Programme and the Food and Agriculture Organization, is, as its name implies, an afforestation/reforestation effort. It was designed to support the U.N. Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021-2030 announced in March 2019, offered as a “proven measure to fight the climate crisis and enhance food security, water supply and biodiversity.”