I FIRST CAME across digital media artist Madeleine Jubilee Saito’s work on social media. While scrolling through a sea of Instagram stories about environmental disasters, civil unrest, and humanitarian strife, I reached a square that made me pause: a multicolor four-panel image from a digital watercolor comic. I took in the top two panels of a gray figure staring out into the sky and then the glimmering, fruited foliage framing the bottom two panels. It felt like a vision from a better, more just future. The text on each panel, though brief, was powerful. I took in each word like a sacred telegram: THE GREAT WOUND / IS HEALED / ALL THINGS / MADE NEW.”

When I was younger, I found comfort in dynamic plotlines nestled in the predictable geometry of print and online comic series. Through Saito’s work, that comfort returned to me, in the form of four panels grappling with climate grief and environmental repair.

When I spoke with Saito about her work, she said that her affinity for comics started in high school. “As a young person, I had a very hard time accessing my own feelings or seeing that my interiority or my life were particularly valuable,” she said. “Comics were a way I could crystallize that value and the meaning of my own interiority for others — make it visible.” Now, Saito’s work conveys the value of the natural world. In her ecological storytelling, we see portraits of people amid towering trees and shimmering waterways. Her human subjects submerge themselves in the elements; her natural subjects invite readers to take a closer look at this numinous world.

Her upbringing in northern Illinois exposed Saito to the tensions between humans and earth. She grew up in a house deep in the woods — “a strip of forest in the middle of this desolate monocrop landscape,” she said, explaining how she saw beauty amid exploitation. “The animals — raccoons and possums — were pests to be managed. Every year the trees and bushes and plants from the forest would encroach further toward the house and every year they would need to be cut back.”

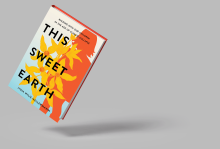

This awareness of the adversarial relationship with the natural world has guided her work and now culminates in her debut book, You Are a Sacred Place: Visual Poems for Living in Climate Crisis (Andrews McMeel, 2025). The first section explores the doom happening parallel to climate collapse. In one story, we see someone curled up in bed, sinking into and verbalizing their sadness post-job layoff. Wildfire smoke chokes the Seattle air around them. In this panel, I see myself, two years ago, numb from financial despair while wildfire smoke cast a noxious orange hue over Philadelphia.