Opinion

My “For You” page is dancing again. Coming off the release of Beyoncé’s country album, Cowboy Carter, the TikTokers have taken center screen and are imitating line dances in celebration of her new sound. Sheepishly, I have been attempting to join in. I don’t dance. Or I should say I do not dance well. I’ve never been classically trained, I’ve got two left feet, and I still have to silently mutter the steps to the electric slide to stay on beat. I’ve consistently struggled to find my rhythm, but I dance anyway.

In 1985, Chicago Mayor Harold Washington passed an ordinance prohibiting city workers from cooperating with immigration police to detain and deport undocumented migrants. With this ordinance, Chicago became a sanctuary city, joining other U.S. cities in resisting policies that criminalize migration. Almost 40 years later, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott has used Chicago’s sanctuary status as an excuse to bus and fly thousands of migrants to the city from Texas, where he has instituted strict migration policies.

Since Texas began bussing and flying migrants to Chicago in 2022, the city has welcomed over 30,000 migrants. These migrants have endured terribly cold winters, undignified housing, and a city divided by feelings of frustration, indifference, and solidarity.

When I say “Christian unity,” what I mean isn’t “Christians should all just agree” or even “Christians should ignore our real differences in doctrine and tradition.” Instead, what I mean by “Christian unity” is that when we center our shared identity in Christ — notwithstanding our differences — we can generate trust and build relationships that bear real fruit, increasing cooperation within the church to address challenges in the world. And I say this knowing that there are often many good reasons why Christians are not unified, including differing views on issues that cut to the heart of our faith, such as our interpretation of scripture, what we believe about the role of baptism, and vastly different governance structures, as well as differing views around contentious issues such as abortion and sexuality. But Christian unity is still worth pursuing because it ultimately strengthens our collective witness, advancing the love of God and work of justice.

Especially for those churches who imagine ourselves to be a mediating middle path in a country where every issue has become sharply partisan, Civil War illustrates that objectivity ends where the suffering of vulnerable people begins.

Standing hand in hand with my fellow classmates at St. Lawrence Catholic Church and School in North Miami Beach, Fla., I couldn’t help but notice how sweaty my hands were. It was 2006, and another 98-degree, humid day in my hometown was upon us. The old church’s air conditioner wasn’t very effective, and I remember I had a feeling I just couldn’t shake — even at the young age of 9: I felt as though something was deeply wrong with me.

I was raised in a primarily Caribbean Catholic tradition, where my family and community emphasized that adhering to the strict rules of the church was what made you a good person. Every morning, my dad would rush me and my sister out the door to school. We would line up with our classes and recite prayers before entering the building, no matter how hot it was outside. During the day, I took religion classes and memorized scriptures my teachers required me to recite at church twice a week. I hated it all.

The gospel writers were not fixated on Mary’s sexual history; it’s the institutional church that objectified her — casting her as a perpetual virgin, elevating her sexual experience (or lack thereof) to be the most important thing about her

Do you ever wonder if calling your representatives makes a difference? Do you ever wonder if prayer yields fruit? Considering all the injustice in the world, I think those are fair questions to ponder.

Since last October, I’ve spent many nights crouched over the bed with my phone on loudspeaker. I’ve been calling my representatives for the passing of H.R. 786, a congressional resolution that urges “an immediate deescalation and cease-fire in Israel and occupied Palestine.” This has been my daily practice.

The Dune series’ ambivalence and criticism about the role of the messiah lends some light on one of scripture’s more enigmatic ideas: the messianic secret.

The story of Zion resonates with the history of African Americans. Blacks and Jews share common legacies of segregation, genocide, and racial domination. No wonder many enslaved Africans understood biblical Israel as a symbol of freedom from bondage. As historian Robin D.G. Kelley explains, the story of Exodus “provided Black people not only with a narrative of slavery, emancipation, and renewal, but with a language to critique America’s racist state.” Exodus was our political compass through the wilderness of slavery. Except we imagined ourselves as the Israelites, America as Egypt, and “Massa” as the Pharaoh whom freedom fighters like Nat Turner and Harriet “Moses” Tubman demanded, “Let my people go!”

But my view of Israel changed when I learned about Palestine in the streets of Ferguson, Mo.

In 1935, across the river from where my family lived, the Nazi-run parliament unanimously passed the Reich Citizenship Law. A deepening of the already emerging racial regime, this law categorized who was a German citizen, initially stripping those of Jewish descent of their citizenship. Proof of Aryan descent became essential to maintain or gain citizenship, and this was done primarily through both ancestral birth certificates and ecclesial baptismal records. This use of sacramental records meant that, according to historian Kyle Jantzen, “Churches became the most important site for the implementation of Nazi racial segregation.”

With their citizenship stripped from them and sensing the deadly direction Germany was headed, my great-grandmother acquired forged baptismal certificates and the family fled. Initially escaping to Palestine, they eventually made their way to the U.S. I was raised Christian. But I still struggle with this, now being a part of the faith that inflicted displacement upon my family. I lack a coherent emotional grasp of this story, but I can feel the rough shape of the loss. That loss is unexpectedly present, something I stumble over. But in this stumbling is a small, personal grace that has transformed my faith, bringing me to worship a God who is not simply for the oppressed but engages in the work of liberation.

The series, which stars Jodie Whittaker (Doctor Who), Bella Ramsey (The Last of Us), and Tamara Lawrance (Kindred), uses the setting of the prison as a vehicle for exploring the immense pressures that society places upon women, particularly mothers.

Jim Wallis is one of the faith leaders who keenly understands the threat of growing nationalism in the church and autocracy in our politics — and the role that Christians must play in stopping it. In his newest book, The False White Gospel: Rejecting Christian Nationalism, Reclaiming True Faith, and Refounding Democracy, he aims to inspire and equip “all who can be persuaded to resist and help dismantle a false gospel that propagates white supremacy and political autocracy.”

If you had told me 11 years ago at my first contemplative retreat that I had ADHD, I would have been skeptical. I was an organized, overachieving Enneagram 3, a bookworm, and a grown professional woman — not a small bouncy boy disturbing his classroom because of his attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The problem, I was told by all around me, was that I lacked spiritual discipline. But just a few hours into the retreat on a Saturday afternoon, I had to admit I wasn’t excelling at the assignment of stillness and silence.

Born in Pittsburg on Oct. 9, 1935, Letha was an independent scholar, writer, editor, and writing consultant who specialized in the intersections of religion and social issues. She passed away on Jan. 9, 2024, at a nursing facility in Charlotte, N.C. She was 88.

Her primary metaphor for God was that of a loving friend. She understood Jesus to be the perfect embodiment of the friendship that God offered. For her, this meant that just like a friend changes their likes, activities, and interests due to the growth of a relationship, God also changes because of God’s friendship with us. In any true and deep friendship, both of the friends, as well as the relationship itself, will necessarily shift and adapt. Nothing can stay the same because deep caring calls for responsiveness. “To think God doesn’t change,” Letha said, “doesn’t account for God to have empathy and compassion for us.” She wasn’t striving to put a particular branch of theology into practice, she just trusted her experience.

Holy Week and Easter are perhaps the most important days in the Christian calendar. Many associate those celebrations with church services, processions, candles, incense, fasting, and penances. However, there is another tradition that many Christians follow — that of tattooing. Historically, Easter was an important time for tattoos among some Christian groups. Today, Christian tattooing happens in many parts of the world and all year around. Some Christians visiting Jerusalem around Easter will get a tattoo of a cross, or a lamb, usually on their forearms.

Some books utterly disrupt you. I was doing research for an essay on St. Augustine and slavery when I first came across humanities scholar Jennifer Glancy’s Slavery in Early Christianity. Reading this book made me realize that everything I thought I knew about the history of Christianity and slavery was wrong.

Though Paul might be a Christ, an “anointed one,” he’s no Jesus. His road does not lead to a Roman cross. Instead of forfeiting power, he’s supposed to accumulate it.

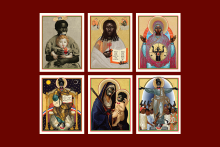

As racist ideas continue to plague U.S. politics, Mark Doox’s Afro-surrealist and satirical graphic novel, The N-Word of God, couldn’t have arrived at a better time.

The book is a visual novel told through depictions of anti-Black images — Black people eating watermelons, Jim Crow caricatures, mammies, and blackface — all stylized in the form of Eastern Christian iconography. This is a style that Doox has termed “Byzantine Dadaism.” Doox’s novel deconstructively takes these caricatures that have historically harmed Black people and reimagines them as symbols of Black resilience and healing, restoring the inherent dignity that belongs to every human being, especially those who have been racialized and subjugated by U.S. anti-Blackness.

I have a testimony: At the end of last year, I felt an unshakable sense of dread about the 2024 elections and all that it could entail. This dread was accompanied by an acute feeling of burnout, fueled by my exhaustion with how broken and polarized our politics have seemingly become and how another election year would test both our faith and democracy. This burnout showed up in restless sleep, nagging fatigue, and a frustrating sense of déjà vu, all of which impacted my mental, physical, and spiritual health.

Hirayama’s mundane work of toilet washing becomes a sanctified act, for one simple reason: He does it for other people.