As many Americans are saying goodbye to summer and enjoying one last vacation this Labor Day, another reality demands our attention.

From actors and writers, to UPS and hotel workers, this summer has indeed shaped up to be a hot labor summer — a term coined by Lorena Gonzalez, executive secretary of the California Labor Federation, to denote a sense of growing momentum for the labor movement.

According to a recent Gallup poll, labor unions are enjoying their highest levels of national national support since 1965. One major reason for renewed labor organizing is the COVID-19 pandemic, as workers started to ask whether a new future for work was possible in the midst of the pandemic. Some of the demands that laborers were making then are still being made now: increased pay, safer working conditions, and flexible schedules. In the U.S., the federal minimum wage is still a paltry $7.25 per hour. Federal minimum wage has not increased since July 2009 but if it had been keeping up with inflation, it would be over $21 an hour today.

What would Jesus have to say about America’s hot labor summer specifically, and the renewed organized labor movement more generally speaking?

With all the recent positive sentiments toward labor unions in the United States, it’s worth noting that a significant source of support for trade unionism has historically come from Christians who directly link Christ to the plight of workers.

Most of the work that depicts Jesus as part of the labor struggle draws on the belief that he was a laborer himself. There is biblical and historical evidence for this. In Matthew 13:55 and Mark 6:3, Jesus is identified as the son of a tekton and a tekton himself. Historically translated as “carpenter,” tekton can mean a variety of things from skilled artisan to day laborer. Ultimately, what we do know is that Jesus was a worker.

The image of Jesus as a worker should shift our understanding of who Jesus was and the type of workers he was linked to. In short, it tells us a lot about Jesus’ class.

New Testament scholar John Dominic Crossan argues that Jesus belonged to the lower classes and worked as a peasant artisan. In the ancient world, there were “haves and have nots,” and Jesus was likely in this latter camp. Crossan explains that Jesus was a “peasant boy in a peasant village,” and was likely forced to do hard labor in order to make ends meet.

As with many aspects of the historical Jesus, we probably cannot know just what kind of worker Jesus was. But for me, it’s important to meditate on Jesus being close to, if not part of, the most vulnerable people in the society in which he lived.

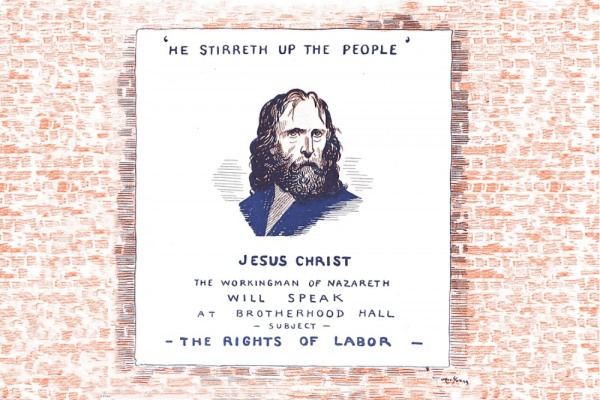

I’m daily reminded of this when I look at a painting that is hanging in my office. The image is a portrait from a 1913 copy of The Masses magazine — a socialist magazine which ran from 1911 to 1917. The magazine supported labor strikes that were often violently opposed by the government, as was the case in the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike of 1912. In the portrait by Art Young, a disheveled Jesus is depicted in the same manner as a union agitator. The text reads: “‘He Stirreth Up the People!’ Jesus Christ, the workingman of Nazareth will speak at Brotherhood Hall – subject – the rights of labor.” The image comes from a time when Christians were unafraid to marshal Jesus’ image to support their fight for a better world.

Inside the pages of the magazine, you’ll also find plenty of poetry that espouses the view that Jesus was a proto-union agitator. This includes Sarah Cleghorn’s “Comrade Jesus.” In the poem, Jesus is depicted as a professional agitator who has participated in “mass meetings in Palestine.” The poem ends with an evocative image:

Ah, let no local him refuse

Comrade Jesus hath paid his dues

Whatever other be debarred,

Comrade Jesus has his red card.

The red card was the universal call-sign of the Wobblies or the Industrial Workers of the World, a radical union which sought to do away with trade unions and organize under “one big union.” Here Jesus is a card-carrying member of this big union and his loyalties to the workers of the world are made abundantly clear.

I asked one of my congregants, Rick, who is a union member, to tell me what Jesus’ status as a laborer means for his faith. He told me that “the Messiah was a member of the working class who preached about social injustices, including economic inequality. I highly doubt he would have sided with management as we know how he felt about merchants and money changers in the temple.” From our perspective, this means the church must be in solidarity with workers.

Embodying this solidarity is something my church has attempted to do. For example, when Rick was on strike, the deacons at my congregation provided support and offered to pay for his insurance during the strike. Your church might not have the resources to extend such an offer, but other smaller acts of solidarity are just as important: “Even taking coffee and donuts to people walking a picket line is very welcomed,” Rick said.

The lives of those who work in this economy are sacred and they deserve rights and benefits, as well as a fair share of the wealth that they are creating. Churches can be a part of creating that world by supporting workers and their fight for fair working conditions and compensation. This Labor Day, Jesus and his red card can show us the way to theologies that support workers’ rights.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!