Opinion

We are in for a difficult four years as a country. During the first four years of Donald Trump’s administration, I did not hesitate to call him a fascist, and looking ahead to his next four years, I am so worried about vulnerable people in this country. I am worried about immigrants. I am worried about queer people and trans kids. I am worried, yes, but I know that even in the most difficult time, miracles are possible.

As a person of faith, I am deeply concerned about what the outcome of this election means, especially for those who will be most vulnerable to threats of mass deportations, retaliation against perceived political enemies, and other actions planned by the incoming administration. Yet we must not follow the example set by the president-elect and his followers: We can and should acknowledge the recent election results as legitimate, even if we are pained by them. I am hopeful that we can use this moment to break the fever of election denialism and rebuild trust in our election system — a shift that will be critical for future elections. Equally critical will be our commitment to advance justice and peace, a commitment that requires us to roundly reject the siren songs of violence, conspiracy theory, and anti-democratic methods.

During the presidential debate in September, then-Republican candidate and now President-elect Donald J. Trump propagated a Facebook rumor that Haitian immigrants in Ohio were stealing neighbors’ pets and eating them. While the rumor has since been debunked, anti-immigrant rhetoric like this makes it easier for lawmakers to drum up support for laws such as Florida’s SB 1718, a law that is meant to address illegal immigration.

When Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, signed SB 1718 last year, he declared it “the strongest legislation against illegal immigration anywhere in the country.” When the bill was first proposed, it included some particularly cruel policies that would discourage immigrants from seeking access to basic services such as rides to church or medical care.

The next four years will be a climate train wreck. Trump and his ilk will dismantle as many policies and regulations as they can. Autocrats and newly influential far-right parties the world over will be emboldened to “drill baby, drill.” More parts of the world will burn, flood, and turn into desert. Refugees — who are treated with God’s passionate care in the Hebrew Bible — will be scorned, vilified, detained, and deported at borders and in global northern countries around the world. It will be painful. And yet, based on the patterns already in place, the world will do its best to look away.

I’ll admit I struggle to face the reality that many in our country — roughly 51 percent of the popular vote, according to current estimates — are feeling some combination of elation, pride, and excitement that their chosen candidate has won. Even in my pain and grief, I know that as a follower of Jesus, I am called to pray for the incoming Trump administration and the people who voted for it. I’m committed to doing that work, but I confess: It feels hard right now.

My 8-year-old came downstairs with tears in his eyes after learning the news today.

“What will happen to the turtles?” he cried. He has been haunted by Trump’s words at the Republican National Convention, as he shouted “Drill, baby, drill!”

Many of us have been working hard for months to shore up the freedom to vote for all citizens. We have knocked on doors, made calls to strangers, signed petitions, watched the news, created content, and equipped leaders on civic engagement strategies, hoping we will get the opportunity to rest after Election Day. For months, we have given our energy, sweat, and tears to ensure our communities are informed and equipped for this election. It seems like it will never end. But here’s the good part: We don’t have to wait until it’s over to get some rest.

In the summer of 2020, I was scrolling through Twitter (now called X) when I saw a video of young protesters gathering near the house of the Chicago Mayor at that time, Lori Lightfoot. They were protesting her heel turn away from the progressive policies on which she had run. In the background of the video the doors of my church, Grace Church of Logan Square, were firmly closed. To have our doors closed to brave and bold young people fighting for justice was not the witness that my church wanted to bear. So, I called several of my leaders and our partner congregation, St. Luke’s Lutheran, and our protest support group was born.

Gutierrez had systematized a living, collaborative, community movement in his ground-breaking work, A Theology of Liberation, published in 1971 in Spanish and two years later in English. Over decades, clerics and community leaders, men and women, across cultures, identities, and denominations, all had contributed, in the smallest way, to the construction of this new way of thinking about — and acting toward — God and God’s glorious creation.

“Fascist” isn’t a word I ever use lightly. It’s not a word that resonates with most Americans, and I’ve worried using that word will only further polarize our deeply divided nation. But Trump’s escalating rhetoric, especially over the past few months, calls for moral clarity: It is time to state emphatically that Trump’s rhetoric is increasingly and dangerously fascist. Since we know that this kind of language creates a permission structure to justify and incite violence, Christians of all stripes must condemn language that crosses that line.

As an adult, I’ve been in many so-called “diverse communities” where there is a lot of racial diversity, but culturally and experientially, it felt very similar to the predominately white church I grew up attending for Sunday school. From the way we worshiped to the food we ate together afterward, these interracial churches seemed to only work because they were comfortable places for white people. In these integrated congregations, white people would often say to me, an Asian American, that they felt so grateful to have so many different experiences and viewpoints reflected in the congregation (“We’re learning so much from different communities”). But those viewpoints were never reflected on the leadership team.

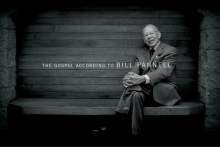

Bill Pannell was an evangelical in the truest and best sense of that word. He believed fervently that humanity needed to be reconciled to God, and to each other. But he was a Black evangelical, who were and are still so different from white evangelicals in America. And that made all the difference in this disciple’s pilgrimage that has now been documented for us.

God’s first house — the tabernacle — is movable, following the Israelites as they wander from Egypt to Canaan (Exodus 40:34; Numbers 1:47-53). The theme of migration continues into Jesus’ life, where Matthew’s gospel tells us that he fled political violence and spent much of his childhood in Egypt (Matthew 2:13-23). Even when he is back in his own country, he is unwelcome in his hometown and “has nowhere to lay his head” (Matthew 8:20).

As an opinion journalist who is also a Christian, I believe my primary responsibility is to provide a myriad of perspectives that challenge or — when necessary — correct readers’ opinions, all in the hope that through reading Sojourners’ opinion section they might realize that Christ is inviting them to make the world a more just place.

For several years, I pastored a small church in the Northwest Bronx. In the summer of 2022, the church leadership decided to dedicate one Sunday a month to do a service project where we engaged in direct political action. It was the summer when Roe v. Wade was overturned, and we focused our attention on reproductive justice. Instead of simply looking at reproductive justice as a pregnant person’s right to receive an abortion, we started thinking of it in broader terms: a better family welfare system in the U.S., honoring the bodily autonomy of birthing people, and taking steps toward improving the material conditions of Black and brown children in the Bronx through mutual aid, collective care, political education, and political solidarity.

The present political and religious environment is both intense and toxic, making any judgements about Israel and Palestine perilous. Anyone who dares speak is immediately subject to interrogation, often followed by indictments of antisemitism, or religious zealotry, or blind ideological bias. It’s hard to articulate a message that cuts beneath entrenched, polarized rhetoric — and even harder to listen. But we must try to speak, for silence is complicit resignation to evil, terror, and calamity.

Last week, as I attended the fourth Lausanne Congress in Incheon, South Korea, I was struck with how much the global evangelical movement has evolved in the past half century, including the advent of new technologies and the explosive growth of Christianity in the Global South, which has reversed the mission field and shifted the epicenter of Christianity increasingly to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. I was also reminded how much global evangelicalism remains stymied by old debates, including overly narrow conceptions of evangelism. The reputation and witness of the church itself plays a major role in evangelism. Doing justice is integral to the cause of evangelization — a conviction and commitment I wish Christians and churches in the U.S. and around the world more strongly embraced.

When my friend introduced me to pop artist Chappell Roan this past April, I had no idea who she was. Now, nearly six months later, I hear about Chappell Roan (the stage name for Kayleigh Rose Amstutz) daily. From drawing massive crowds at Lollapalooza to having one of the most streamed albums of the summer, Roan’s quick rise to fame has been impressive.

My friend described Roan as the “situationship singer.” A “situationship” a term coined by Generation Z, is a noncommittal or undefined romantic or sexual relationship. “Casual,” the fifth track on Roan’s The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess, grieves a situationship. In it, Roan describes a relationship that fails to evolve into something beyond a pattern of casual, sexual encounters. There’s a confession in Roan’s bridge that’s so honest and unexpected, that it took me by surprise upon first listen. She says, “I try to be the chill girl that / Holds her tongue and gives you space / I try to be the chill girl but / Honestly, I’m not.”

For those who grew up in the conservative Christian world as Roan did, lamenting casual sex is familiar territory. But Roan and other Gen Zers aren’t lamenting casual sex, hookup culture, or situationships because they believe their “sexual purity” is tied to their salvation. Rather, they seem to be lamenting a sex-positive culture that doesn’t live up to the hype.

All magazines have an assumed sense of “we” and “us,” a shared purpose that unites the writers, editors, artists, and readers. Who am I, who are all of you, and what do we have in common as we stare at these words on glossy pages or screens?

But while assessing who wins a debate can be fairly subjective, determining who wins the upcoming election can’t — or shouldn’t be. As we’ve learned since 2020, confidence in our electoral system has increasingly become a partisan issue, with over 70 percent of Republican voters believing that President Joe Biden’s win in 2020 was illegitimate, a belief fueled by the pernicious, big lie that the election was stolen due to widespread voter fraud. Changing these numbers and restoring bipartisan confidence in our electoral system will require real work — and leadership from our elected officials.