Opinion

As an adult, I’ve been in many so-called “diverse communities” where there is a lot of racial diversity, but culturally and experientially, it felt very similar to the predominately white church I grew up attending for Sunday school. From the way we worshiped to the food we ate together afterward, these interracial churches seemed to only work because they were comfortable places for white people. In these integrated congregations, white people would often say to me, an Asian American, that they felt so grateful to have so many different experiences and viewpoints reflected in the congregation (“We’re learning so much from different communities”). But those viewpoints were never reflected on the leadership team.

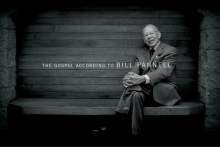

Bill Pannell was an evangelical in the truest and best sense of that word. He believed fervently that humanity needed to be reconciled to God, and to each other. But he was a Black evangelical, who were and are still so different from white evangelicals in America. And that made all the difference in this disciple’s pilgrimage that has now been documented for us.

God’s first house — the tabernacle — is movable, following the Israelites as they wander from Egypt to Canaan (Exodus 40:34; Numbers 1:47-53). The theme of migration continues into Jesus’ life, where Matthew’s gospel tells us that he fled political violence and spent much of his childhood in Egypt (Matthew 2:13-23). Even when he is back in his own country, he is unwelcome in his hometown and “has nowhere to lay his head” (Matthew 8:20).

As an opinion journalist who is also a Christian, I believe my primary responsibility is to provide a myriad of perspectives that challenge or — when necessary — correct readers’ opinions, all in the hope that through reading Sojourners’ opinion section they might realize that Christ is inviting them to make the world a more just place.

For several years, I pastored a small church in the Northwest Bronx. In the summer of 2022, the church leadership decided to dedicate one Sunday a month to do a service project where we engaged in direct political action. It was the summer when Roe v. Wade was overturned, and we focused our attention on reproductive justice. Instead of simply looking at reproductive justice as a pregnant person’s right to receive an abortion, we started thinking of it in broader terms: a better family welfare system in the U.S., honoring the bodily autonomy of birthing people, and taking steps toward improving the material conditions of Black and brown children in the Bronx through mutual aid, collective care, political education, and political solidarity.

The present political and religious environment is both intense and toxic, making any judgements about Israel and Palestine perilous. Anyone who dares speak is immediately subject to interrogation, often followed by indictments of antisemitism, or religious zealotry, or blind ideological bias. It’s hard to articulate a message that cuts beneath entrenched, polarized rhetoric — and even harder to listen. But we must try to speak, for silence is complicit resignation to evil, terror, and calamity.

Last week, as I attended the fourth Lausanne Congress in Incheon, South Korea, I was struck with how much the global evangelical movement has evolved in the past half century, including the advent of new technologies and the explosive growth of Christianity in the Global South, which has reversed the mission field and shifted the epicenter of Christianity increasingly to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. I was also reminded how much global evangelicalism remains stymied by old debates, including overly narrow conceptions of evangelism. The reputation and witness of the church itself plays a major role in evangelism. Doing justice is integral to the cause of evangelization — a conviction and commitment I wish Christians and churches in the U.S. and around the world more strongly embraced.

When my friend introduced me to pop artist Chappell Roan this past April, I had no idea who she was. Now, nearly six months later, I hear about Chappell Roan (the stage name for Kayleigh Rose Amstutz) daily. From drawing massive crowds at Lollapalooza to having one of the most streamed albums of the summer, Roan’s quick rise to fame has been impressive.

My friend described Roan as the “situationship singer.” A “situationship” a term coined by Generation Z, is a noncommittal or undefined romantic or sexual relationship. “Casual,” the fifth track on Roan’s The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess, grieves a situationship. In it, Roan describes a relationship that fails to evolve into something beyond a pattern of casual, sexual encounters. There’s a confession in Roan’s bridge that’s so honest and unexpected, that it took me by surprise upon first listen. She says, “I try to be the chill girl that / Holds her tongue and gives you space / I try to be the chill girl but / Honestly, I’m not.”

For those who grew up in the conservative Christian world as Roan did, lamenting casual sex is familiar territory. But Roan and other Gen Zers aren’t lamenting casual sex, hookup culture, or situationships because they believe their “sexual purity” is tied to their salvation. Rather, they seem to be lamenting a sex-positive culture that doesn’t live up to the hype.

All magazines have an assumed sense of “we” and “us,” a shared purpose that unites the writers, editors, artists, and readers. Who am I, who are all of you, and what do we have in common as we stare at these words on glossy pages or screens?

But while assessing who wins a debate can be fairly subjective, determining who wins the upcoming election can’t — or shouldn’t be. As we’ve learned since 2020, confidence in our electoral system has increasingly become a partisan issue, with over 70 percent of Republican voters believing that President Joe Biden’s win in 2020 was illegitimate, a belief fueled by the pernicious, big lie that the election was stolen due to widespread voter fraud. Changing these numbers and restoring bipartisan confidence in our electoral system will require real work — and leadership from our elected officials.

Christian engagement in American patriotism has often gotten a bad rap, and rightly so: All too often, a healthy love for one’s country (patriotism) seeps into a pernicious love of blood and soil (nationalism), with the latter often marked by a sense of superiority, domination, or ethnocentrism. But instead of offering a strong counter-witness to these toxic impulses, Christians in the U.S. have often led the way, twisting the gospel to support American nationalism. Understandably, some Christians — both now and in the past — have responded by rejecting nationalistic forms of patriotism as something incompatible with following Jesus. As a Christian, I believe the answer isn’t to altogether reject patriotism, but instead to redeem it.

The works of J.R.R. Tolkien — The Lord of the Rings chief among them — have been a passion of mine since elementary school. The story of how four lowly hobbits, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin, come to change the entire course of their world’s history through their decency, courage, and stubborn perseverance still resonates as powerfully for me today as it did then. There’s a “root for the underdog” theme in Tolkien that resonates with my love of working for social justice, and explains why I’ve always been drawn to biblical figures like Moses and Mary, mother of Jesus, who came from humble beginnings and accepted God’s call to play a key role in transforming the world.

Public transportation shapes our worship, our theology, and how we live out Christ’s call to love our neighbor. If we are to learn to love our neighbor, we must then ask who they are, as the expert of the law did in Luke 10:29. Jesus responded with the Parable of the Good Samaritan and invited the man to go and do likewise — to be the one who shows mercy. To be a neighbor is to show mercy, which requires a kind of knowing. I learned who my neighbors were by taking the bus. By being with them, I grew in knowledge of them. By growing in knowledge of them, I grew in love for them.

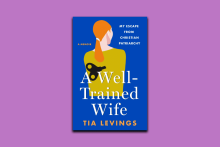

Tia Levings made a decision for herself and her children on October 28, 2007. With the help of a priest, she planned for an escape from her abusive husband. “I heard a voice say, ‘RUN,’” she writes in her memoir, A Well-Trained Wife: My Escape from Christian Patriarchy.

Ten years ago, Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager, was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Mo. Young people gathered at the local police station refusing to accept this as just another “unfortunate incident.” They demanded answers and accountability; their determined stance sparked a movement for racial justice that this nation had not experienced in decades.

Even in the depths of high-control religion, there were moments of being fed and cared for that I did not know I missed until I did.

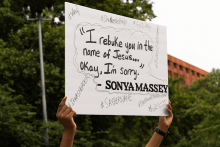

How does a Black woman call for help and get killed by the people who came to support her?

First unveiled in April 2023, and endorsed by more than 100 conservative organizations, Project 2025 is a 922-page document that serves as a to-do list for the next conservative president to accomplish. Activists, journalists, and many religious leaders have been warning the public for months about what they see as some of Project 2025’s more extreme policy proposals and the ways in which the blueprint would push our nation toward autocracy and Christian nationalism.

In the quiet oratory of Holy Wisdom Monastery in Middleton, Wisc., I spent my mornings gazing at the face of Jesus. On the far wall of the room where we prayed hung an icon of Jesus holding a tablet that read, “Behold, I make all things new.” Outside the prairie was a technicolor parade of coneflowers, whorled milkweed, and purple loosestrife, while robins, cardinals, and song sparrows continued their song; but it was hard for me to believe that Christ was making things new in the present.

No wonder it is so difficult to integrate authentic spirituality into the world of secular politics — which often measures worth in terms of winning and acquiring. The values of our political culture often contradict the wisdom of faithful Christian community. That’s why President Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw his candidacy for reelection felt so breathtaking. Voluntary relinquishment of political power is not commonly seen as a virtuous act, but rather a disorienting, shocking abandonment of prevailing norms.