Gun Violence

Leckey's lyrics are soaked in Catholic tradition. When writing songs on Hell Gate, Leckey asked herself: “What if I just full-send it with the Catholic terminology and imagery and tradition, and just do my own thing with it? I think of it as a reclamation and a repurposing.”

Many of us are feeling fear, disorientation, or anger at this moment. As Christians, we need to meet perilous feelings with a resolve to follow Jesus and remember his teachings: The truth will set us free, and we must learn to love our enemies.

I ONLY HAD one child. His name was Damien Purnell. He was 31 years old. In 2017, January 13, I got the worst call of my life. I was at work, and I found out my son got shot five times at my house. I hibernated for five years. And when I say hibernated, I really did. I only went to work and that was it. I was hurting so much inside. It was a pain that was unbearable. My husband was my support system. We cried with each other. I was never mad at God. I finally started getting up and getting out.

After each shooting, Angela Ferrell-Zabala rejects the inevitable chorus of “thoughts and prayers” — but not because she dismisses the power of prayer. Religion is the cornerstone of what drives Ferrell-Zabala to action as the first-ever executive director of Moms Demand Action, a network of volunteers working to protect people from gun violence and part of Everytown for Gun Safety. Yet she knows that faith without action isn’t enough to address the estimated 132 gun-related deaths in the U.S. each day.

When I was living on the West Side of Chicago, friends and family would often say that they couldn’t comprehend why I would want to live in such a “dangerous” area. The exchange would usually go something like the following: “I can’t imagine why you’d want to live in Chicago, considering all the gun violence.” “Are you worried about me being shot by the police?” “Well, no. The criminals are the ones who are shooting people.” “The police shoot people too. And there’s a reason the ‘criminals’ are resorting to violence.”

I would then go on to explain the antecedents to Chicago’s gun violence: racial segregation and systemic disinvestment. Beginning in the 1950s and into the ’70s, white Chicagoans fled the South and West Sides because they couldn’t imagine being neighbors with Black people. Because of this, these areas became predominantly Black, and the city has refused to invest resources into these neighborhoods to reverse their poor conditions. The South and West Sides are still suffering from disinvestment today, and this disinvestment is a major contributor to gun violence.

AFTER A TEENAGER shot dead 19 children and two teachers in an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, last year, I spent two weeks putting my children on the bus to school with a pit in my belly. Then the term ended, and I breathed relief. I would not have to live with this low-level dread for another year.

My family has been on sabbatical in South America for the past 12 months, homeschooling our three boys. Though we’ve faced other risks, the possibility of my kids being shot in school was not one of them. Not only were they not attending school, but the countries we visited also have stricter gun regulations than the United States.

In the U.S., the purchase of guns has soared — gun ownership is estimated to be more than 120 per 100 people, according to GunPolicy.org. Gun-related deaths in the U.S. also top every other high-income country, at more than 12 per 100,000 people annually. Compare that to Ecuador, where we spent part of our sabbatical. In 2017, it had 2.7 guns per 100 people and approximately three gun-related deaths per 100,000 people. Our sabbatical year has been a window into what it’s like to parent school-aged children without the shadow of school shooting anxiety.

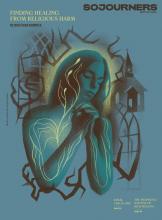

Healing from religious harm: Why compassionate community is part of the journey.

Justin Jones is a Tennessee state legislator representing Nashville. He spoke with Sojourners’ Mitchell Atencio.

What they were trying to do wasn’t just expel us, but the movements we are standing in solidarity with. It’s not ironic that it happened on the day before Good Friday. They tried to crucify democracy and I [was reinstated] the Monday after Easter as a testament to the resurrection of a movement for multiracial democracy here in the South. The resurrection of a Third Reconstruction [is] being led by students and young people — that’s a very powerful vision. If it’s possible here in the South, if it’s possible in Tennessee, that should give us some hope in the nation.

A shooting at a private Christian school in Nashville, Tenn., on Monday morning, left multiple victims before police "engaged" the gunman, leaving the suspect dead, local officials said.

THE LEADING CAUSE of death for children in 2020 wasn’t COVID-19. It wasn’t cancer. And it wasn’t car crashes. Rather, more than 4,300 of our children in the United States died by firearms — the first time in at least 40 years that guns have accounted for more deaths than motor vehicle incidents.

The numbers are stark: More than 110 people in the U.S. are killed every day with guns, while more than 200 others are shot and wounded. “Gun violence in any form — any form — leaves a mark on the lives of those who are personally impacted,” Giselle Morch, a deacon and mother whose son, Jaycee, was shot and killed in their home, told Sojourners. “So many of us will never be the same.”

On July 19, 2017, Morch took her grandson to Vacation Bible School, where she played the role of the Lord in a skit from Judges about Gideon and the Midianites. “One of the lines was ‘For God and for Gideon,’” Morch said. “And when I got home, that’s when the battle was: That’s when my own son was murdered — my son who said, ‘I may not change the world, but I want to inspire many.’”

One thing about the senseless loss of Jaycee has always been clear to Morch: “This could have been prevented.” Shortly after he was killed, Morch began volunteering with Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America to advocate for cultural and legislative change. She has since joined Everytown for Gun Safety’s Survivor Fellowship Program to connect with others who have been impacted by gun violence. “There are others in this movement, because it’s not a moment,” Morch said. “A moment was when my son died; a movement is the call to action to make the change so that nobody else does.”

A judge sentenced Travis McMichael to life in prison on Aug. 8 for committing federal hate crimes in the 2020 killing of Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man shot while jogging through a mostly white Georgia neighborhood in a case that probed issues of racist violence and vigilantism in the United States.

While reducing the prevalence of guns in our society is essential, I am wary of religious gun control efforts that focus primarily on federal gun legislation because laws ultimately rely on frameworks of punitive justice, criminalizing anyone who breaks the law. A holistic approach to gun violence should imagine new alternatives for a safer society — alternatives that go beyond the criminal legal system and gun control laws. To imagine these alternatives, we can turn to the lessons of the transformative justice movement, which seeks to address violence without relying on state violence, police, or prisons.

The protesters gathered to raise their voices for gun control and lament gun violence three days after a gunmen killed 21 people in a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas.

“I hate, I despise your vigils,

and I take no delight in your school shooter drills.

Even though you offer me your thoughts and prayers,

I will not accept them;

and the offerings of well-being of your collection plates

I will not look upon.”

It has been hard to read any of what has been written about the mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas. At some point, you start to wonder if we have convinced ourselves that words speak louder than actions.

On the seventh anniversary of the martyrdom of the Mother Emanuel Nine, we still need to heed the text they were studying that evening.

Her thoughts on guns didn’t immediately change; slowly — as the PTSD and long-term effects of her injuries continued — Schumann began to question the narratives around guns she had grown up with her entire life. Now she’s asking others to join her in questioning the stories we’ve been told about gun violence in the United States.

With each new instance of gun violence, creation cries out with the victims. Creation also helps us center ourselves in relation to God when God feels absent.

This year has been difficult beyond description for so many people. While the COVID-19 pandemic has understandably occupied front pages across the country and around the globe for much of the past six months, another destructive wave continues to fester, creating so much pain and grief: our national plague of gun violence, which claims 100 lives a day. Together, the two crises have become a toxic combination.

“MY BROTHER WAS killed in 2007, and I watched my mom avoid that area for years. When there’s a space where someone has been murdered, you can feel the toxic energy in that space. And I realized there are these toxic holes being left around Baltimore, and it shouldn’t be that way. When people are murdered, the space should be sacred ground—where they lost their lives to violence. Just like the Bible talks about the blood crying out from the ground when Cain killed Abel, when blood cries out we should show up to answer with love and with light, honoring that person.

We ask people facilitating rituals to show up with love in their body. Grief is okay, some sadness is okay, but mostly a feeling of joy at how much this person meant to the world, love for the neighborhood, and compassion for their family and loved ones.