D.L. Mayfield is a neighbor and writer in Portland, Ore. Their book, The Myth of the American Dream: Reflections on Affluence, Autonomy, Safety, and Power was released in May 2020.

Posts By This Author

She Survived a Shooting. Now She's Disarming Her Christian Critics

Her thoughts on guns didn’t immediately change; slowly — as the PTSD and long-term effects of her injuries continued — Schumann began to question the narratives around guns she had grown up with her entire life. Now she’s asking others to join her in questioning the stories we’ve been told about gun violence in the United States.

The Complicated Nostalgia of Seeing My Evangelical Childhood on Film

Despite all the outsized power and privilege white evangelical communities hold, there is a dearth of spaces where people can process what it means to have grown up in the belly of it. Fortunately, there’s a whole slew of new films and documentaries that focus on white evangelical youth culture, offering some of us the chance to reflect on our upbringings as we figure out what it means to have white evangelical roots in a post-Trump world.

In Push to Reopen, American Evangelicals Fall Prey to Political Strategy

An acquaintance of mine on Facebook recently posted something different than her usual scripture verses. She shared a petition asking Florida to stop mandatory shelter-in-place orders. “It’s not that I don’t want people healthy, it’s that I don’t want my freedom taken from me,” she wrote.

American Individualism vs. Loving Your Neighbor

The problem is not only with the corporations struggling to make choices when profits are on the line. As a culture infused with the values of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, Americans value individualism and have a hard time understanding their role in community health measures. When we are taught to prioritize our individual rights and needs (see the discussions about guns, vaccines, and universal health care), it quickly leads to seeing other people as our enemy instead of a neighbor to protect. And that’s where religious communities must lead.

This Is How We Let Abuse Thrive

Wade Mullen uncovers the strategies that allow abuse to happen in the church.

IN THE PAST two years, prominent pastors and church leaders—including Willow Creek’s Bill Hybels, the Village Church’s Matt Chandler, and Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary’s Paige Patterson—have been accused of perpetrating or enabling abuse within their large institutions. By the time this story goes to print, another once-trusted person or institution will likely be proven to be corrupt, unreliable, and abusive.

While he was a youth pastor, Wade Mullen heard many of these hard stories from the teens and families he served. But when Mullen reported this abuse to his supervisor in accordance with state protocols, he was shocked when the church leadership dismissed it out of fear for what could happen to the institution. “Do you realize what reporting could do to that family? To this church?” asked a pastor. “These kids could take us all down with their storytelling.”

Despite this resistance from church leadership, Mullen reported the abuse to the appropriate civil authorities. After working for months to make clear why following reporting protocols was important for the safety of the vulnerable, he eventually resigned from the church.

The experience spurred Mullen to pursue a doctorate in organizational leadership, with a dissertation that examined how organizations respond to events that threaten their image. In his research, he told Sojourners, he “collected and analyzed nearly 300 media reports of American pastors of evangelical churches charged with a crime in the years 2016 and 2017.” Mullen, who now runs the M.Div. program at Lancaster Bible College’s graduate school, was profoundly affected. “I was stunned to discover that more than 200 were sex crimes, the vast majority of which were committed against children,” he said. “I was filled with grief and anger as I read descriptions of child sexual abuse, rape, child pornography, sex trafficking, and prostitution committed by those in positions of trust.”

In other words, Mullen became an expert on the very questions many of us have been asking lately: How do these systems end up enabling perpetrators while silencing victims? And—more importantly—how do so many of us let it happen, especially within the church?

What 'Leaving Neverland' Reveals About Systems of Abuse — and What the Church Can Learn From It

Photo via Leaving Neverland Documentary on Facebook.

It is a difficult film to watch, but it is not sensationalized in any regard. Reed was not interested in making a film to convince anyone of Jackson’s guilt. Instead, the camera is fixed on both Wade Robson and James Safechuck, the men who are alleging the abuse, and their families. It is an incredibly important experience, and almost disorienting as a viewer, to give so much power to these men and their stories. They describe the reality of what it means to be someone who has survived long-term sexual abuse as a child, at the hands of someone who was much older and infinitely more powerful. The secondary thread running throughout the film is the story of their family members — the mothers, the siblings, the wives — who describe how this type of abuse happens, and how victims are silenced for decades.

School of Lies

Christian homeschooling texts are based on the idea that white Protestants should oversee our world.

WHEN DID YOU realize your textbooks lied to you?

I grew up in the Pacific Northwest and was homeschooled by my mother, the wife of a conservative Christian pastor. I didn’t think too much about my education until the 2016 election when I became increasingly alarmed by the enthusiastic support white evangelicals gave to Donald Trump. When Trump ascended into office, riding in on the phrase “Make America Great Again,” my memory was pricked. I had heard all this before.

To check it out, I obtained two history textbooks that I had used growing up. In 1999, when I was a sophomore in high school, 1.7 percent of the U.S. population was homeschooled. By 2012, the percentage had doubled. When I was homeschooled, there were three prominent curriculum producers for Christian homeschooling: Abeka Press, Bob Jones University Press, and Accelerated Christian Education. Abeka remains the most popular. Officials at Abeka, according to the Orlando Sentinel, would not say how many textbooks the company sells or release the number of schools that use their curriculum, but said that “it is safe to say that millions of students” have used the materials.

3 Ways Christians Can Address Gentrification

Tips for congregations wrestling with the mass displacement crisis.

IT IS EASY to feel overwhelmed or paralyzed by the systemic nature of how money and development works, or—if you are a gentrifier yourself—to feel guilty to the point of inaction. While each neighborhood and context may differ, individual Christians and congregations can live into beliefs and practices that help address the crisis of mass displacement in the U.S.

1. Be Your Neighbor’s Keeper

Pastor Mark Strong believes the best thing Christians in a gentrifying city can do is to hear and understand the stories of their neighbors. In Portland, he says, most of the African-American churches have suffered in silence. White Christians have not been aware of the crisis taking place next door to them. Intentional relationships and active listening can begin to remedy this.

Finding and investing in ongoing relationships with people most at risk of displacement is vital. There are myriad ways to do this: living in lower income apartments, investing in the public schools, seeking out community organizers and grassroots nonprofits—and learning from local churches with long-term roots in the community.

2. Know the Plan

Tim Keller advises people moving into a neighborhood at risk of gentrifying to see if a plan is in place to minimize displacement, and if not, to ask how one could be created. This plan—put together by the local government, nonprofit agencies, developers, and businesses, along with churches and community leaders—is vital to understanding both the issues specific to the neighborhood and ways to hold all accountable. Without a plan in place to shield properties and families from the market, middle-class and wealthier individuals will be directly contributing to gentrification.

How Churches Are Confronting Gentrification

Loving our neighbors means doing something when they're forced out.

GENTRIFICATION DOESN'T look the same everywhere, but it is happening in most major cities in the U.S. And this isn’t just about the brewpubs, the coffee shops, or even the “cash for houses” signs. As Peter Moskowitz writes in his book How to Kill a City: “Gentrification is the most transformative urban phenomenon of the last half century, yet we talk about it nearly always on the level of minutiae.”

The underlying connection is the economic reality: “Gentrification is a system that places the needs of capital (both in terms of a city budget and in terms of real estate profits) above the needs of the people,” Moskowitz writes. This came up often as I talked with people involved in the complex world of housing and development.

Christian theology offers compelling reasons why individuals and communities can and must care about this dynamic. At the core of Christianity is the call toward love of neighbor. When the poorest of your neighbors continually face the brunt of a system designed not to care about them, gentrification becomes a church issue.

What ‘The Prophetic Imagination’ Has Meant to Me

Five Christian leaders on the influence of Walter Brueggemann’s classic book in their life and ministry.

Five Christian leaders on the influence of Walter Brueggemann’s classic book in their life and ministry.

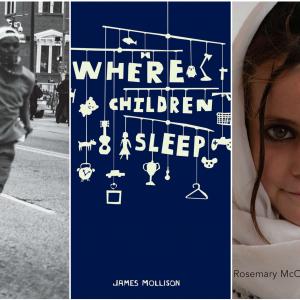

9 Books for Confronting the World's Disparities

Reading can help us grapple with the truth that the world is a very unequal place.

BOOKS ARE WINDOWS into other worlds and glimpses of experiences not our own. One of the most powerful ways books have worked in my life is to illuminate the truth that the world is a very unequal place. It started at a young age for me, my childish mind consumed with stories such as that of Helen Keller (and her teacher, Anne Sullivan, who for several years lived in a “poorhouse”) and missionary biographies of people such as Amy Carmichael and Gladys Aylward, who worked with children who had been trafficked or orphaned in other countries.

Even as a child I puzzled over why some children suffered so greatly and others didn’t. It wasn’t fair.

As much as I loved stories with fairy-tale endings, such as The Secret Garden or The Little Princess, I returned constantly to narrative nonfiction that exposed me to a wider, morally complex world. And this drive never left me.

Today, there are many books that address the topic of inequality in fresh, insightful, and provoking ways.

Church Planting and the Gospel of Gentrification

Are we seeking the "welfare of the city," or just our own?

LAST YEAR, STANDING at a microphone in front of our city council at a town-hall meeting, I came to a stark realization: I needed a theology of gentrification.

There I was, shakily demanding that the city not tear down our neighborhood’s one and only park to build a “revitalization” project complete with brew pubs and shared workspaces. I looked at the row of people seated at the city council table, frowning slightly at me, and worked up my courage, pretending I was channeling the tiniest bit of the pope.

“We have a moral responsibility to consider those who don’t have resources and how we can best serve them,” I said, my cheeks flushed. The architect talked about the need for income-generating elements, the secretary entered my remarks in the meeting record, and the developers changed none of their plans. As helplessness crept up into my heart, it became clear that I had no idea what I was doing and needed some instruction.

The irony was not lost on me. I had spent years studying how to do good and how to spread the good news. I got my degree in Bible and theology with a minor in intercultural studies; I volunteered with refugee resettlement agencies for more than a decade and joined a mission order among the urban poor for three years. I can quote the Bible and recite a theology of cultural engagement frontward and backward; I can wax poetic about God’s preferential option for the poor. And yet, in my 13th year of residing in a neighborhood mostly inhabited by people on the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum, I feel lost in the face of the most pressing realities confronting my neighbors.