Opinion

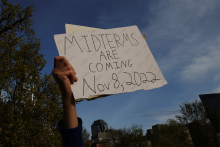

Since 2020, a rolling coup of voter suppression laws has left 55 million voters living in states with restrictions on who, how, when, and where people can vote. Also alarming are reports that the majority of Republican candidates in the midterms “deny or question” the 2020 election results. At times, it feels as though the loudest political opinions are coming from people who want to suppress the vote or peddle lies about the 2020 election. But when poor and low-income people, alongside clergy, moral leaders, and activists vote for an agenda that promotes human rights and dignity, we have the power to make a difference.

The message of assimilation makes me uncomfortable because it requires me to celebrate the loss of other people’s culture, traditions, and languages in order to alleviate the fears that white people, including Christians, might have about a diverse society where their position as power brokers of society may be threatened. It is akin to saying, “White Christians, please do not fear immigrants because they, too, will submit to white supremacy and blend into it as best as they can, even with their non-white skin and features.”

As soon as the pastor began to speak, I rose and turned up the aisle, only looking back once in a small act of self-righteous defiance. I hoped the speaker would catch my gaze and feel convicted over the heresy he preached. Pictures of Black Lives Matter protests scrolled across the screen, confirming in my mind that leaving was the right decision.

The church should be a place where people with divergent political views can coexist and be in fellowship because our unity in Christ supersedes our political and partisan loyalties. As the Apostle Paul reminded the Galatian church, in Christ “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” But that’s not often what we see in our churches today, is it?

Whether the restrictions that undermine compassionate decision-making are imposed by law or systemic inequalities such as poverty, the moral imperative to support careful, compassionate decision-making should drive public policy away from any such restrictions.

The causes of the flooding in Pakistan and climate-fueled catastrophes around the world are a direct result of the out-of-control consumption and production patterns of the global North — the nations in the northern hemisphere that share similar social and political distinctions like market-based economies.

I pondered the question for a minute, gave a quick answer, and reiterated some things that I mentioned earlier in the lecture: If we can embrace an understanding of God and a spirituality that is informed by the lived experiences of Black Latinxs, then perhaps we can better understand more of the fullness of God. But as I drove home and thought about this student’s question, I realized I could have answered differently.

Societally we focus a lot on spanking, I think, because it seems to draw such a line between barbarism and civility, or, seen from the other perspective, between parents who are serious about discipline and those who are wishy-washy. But spanking isn’t the issue behind the issue. The issue behind the issue is authority — the right to exercise power.

As Christians, we need to keep denouncing the most blatant examples of Christian nationalism from politicians, faith leaders, and groups like the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers who participated in the Jan. 6 insurrection. Yet if we care about the integrity of the Christian faith, there is a more difficult — but equally important — challenge beyond these denunciations. We also need to address the subtle but insidious versions of Christian nationalism that so often seep into our churches.

There’s a kind of willful ignorance horror-averse Christians demand, because the truth is we don’t want to sit with the shadows or go down into the basement. We want to sweep all the ugly parts of life back under the bed where they might go bump in the night but won't trouble us in the light of day.

In current times, the idea of the heathen underpins “a White American Christian superiority complex.” Lum explores this through the white savior trope, pointing to the historical example of how many white Americans positioned themselves “in opposition to the heathen world… [in order] to give themselves a venue for the evangelizing work that marked them as the givers [rather] than recipients of aid.” Within the context of the United States, “heathen” has become a racial and classist designation meant to distinguish between the so-called “first world” and the “third world.”

Far too many Christians cling to a stubborn belief that individual acts of charity are sufficient to fulfill their obligation to help all those experiencing hunger and poverty. While acts of charity like donating to a regional food bank or volunteering at a local soup kitchen are commendable and indeed necessary, they are not sufficient. Christians not only have a duty to do good works through individual charity, but also to urge their political representatives to do what is in their power to end hunger in the U.S. and around the world.

There are large swaths of the Bible that the lectionary skips over. And while there are lots of reasons for not including certain passages, it doesn’t take too long to notice one major pattern: Passages that are uncomfortably violent (or just angry) are frequently left on the cutting room floor, and consequently left out of Sunday worship.

When my husband and I started fertility treatment, we intentionally stopped going to church. Due to various traumatic religious experiences, we had been floating for over a year and we remained undecided on whether belonging to any religious organization would be part of our future. Then we went to a church service on Father’s Day weekend. Belting pop songs about the joy and goodness of God was already too much. But then they asked all fathers to stand and it broke us. Around this time, we alerted a small group of people that we were beginning fertility treatment and taking a break from church service.

Honk for Jesus follows Lee-Curtis and his wife First Lady Trinitie Childs (Regina Hall) as they prepare a grand reopening for their Atlanta-area megachurch.

While there’s no magic solution, now is the perfect time to make sure every eligible voter nationwide has everything they need to cast their vote, which increasingly means possessing knowledge, motivation, and determination. Here are five concrete and actionable ways that each of us can help empower and inspire every eligible voter to vote this November.

In Leviticus 25, God instructs Moses and the people of Israel to institute a year of Jubilee. Every 50 years, at the blast of a trumpet, the Jubilee would mark a moral and economic shift in society: Slaves were set free, land was returned to its original owners, and any outstanding debts were eliminated (25:1-12). Similarly, in Deuteronomy 15, God says that every seven years, creditors should “remit the claim that is held against a neighbor” because “the Lord’s remission has been proclaimed.” In the New Testament, Jesus instructs his followers to pray “forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors” (Matthew 6:12, Luke 11:4). Scripture is clear when it comes to debt abolition and the freeing of the debtor: God demands a society that delivers justice and freedom to all and rejects a society that physically and rhetorically shackles its people.

Gutsy introduces us to dozens of trailblazing women who are living lives of justice, truth, love, leadership, humor, and reconciliation. The show, produced and hosted by Hillary and her daughter Chelsea Clinton, while not explicitly “faith-based,” is rich with examples of women cultivating the common good. In a recent interview, Chelsea Clinton told me that there are as many ways to be gutsy “as there are women in all of our lives.”

The WCC convenes an assembly only once every eight years. The agenda always includes electing a new, 150-member Central Committee, approving reports and making formal statements on pressing international issues. But that’s not at the heart of what happened in Karlsruhe, nor has it been in the four previous WCC Assemblies I’ve attended.

If you or a loved one have been impacted by suicide or self-harm, there is nothing to be ashamed of. Scripture teaches us that when one person suffers, we all suffer. Yet if you are in a place of active suicidal ideation, or having self-harming thoughts, it can feel like you have been completely swallowed by the dark; it’s a lonely and terrifying place. But here is the truth: You are wanted on this earth.