Opinion

Historian Timothy E.W. Gloege explains in his book Guaranteed Pure that before the events of Haymarket, Christian evangelist Dwight L. Moody conspired with local capitalists such as Cyrus McCormick Jr., one of the managing partners of International Harvester Company, to thwart the 1886 strike altogether. Within the story of the Haymarket affair, we can find a number of political tensions that are still within Christianity today. One major tension still animating Christian discourse is this: What happens when Christians side with the wealthy instead of the poor and working class?

My early suspicion of Cone was reflexive. I had been formed in the intercessory prayer meetings of pious Afro-Caribbean Pentecostalism and naturalized in the halls of white evangelical academia during the so-called “post-racial” years of the Obama presidency. In those churches of my youth, racism was real, “but not nearly as bad as it had been in the past.”

Like many during the COVID-19 pandemic, I returned to The Office because I craved something familiar. Rewatching the show led me to this realization: The Office is the first TV series to portray the good, the bad, and the awkwardness of religion in a way that I relate to as a Christian.

Our country is rolling back reproductive health access in the name of “choosing life” while refusing to support life’s development in utero and post-birth. We also have not ensured that people who give birth or care for children have paid family and medical leave, workplace protections, or even access to health care facilities. In states like Mississippi and Alabama, budget pressures are forcing many rural hospitals to close, cutting off the only point of care before, during, and after labor.

Half a century later, a lot has changed, but we remain committed to inspiring Christians across every tradition to put their faith into action for justice and peace and strengthening faith-inspired movements for change.

When most people consider the holy month of Ramadan, the 30 days of fasting and reflection for Muslims, they may not picture a millennial in a hijab connecting the Qur’an with environmental justice through Instagram hashtags like #greenramadan and #ecomuslim. But Saarah Yasmin Latif is on a mission to help people of all religious traditions connect their faith with individual and collective acts to sustain the earth.

Immoral exemplars leave us to grapple with a host of difficult ethical questions. Among these are certainly questions about their status and the value of their work. But these are not the only — or even the most important — issues. We also must consider the concerns of survivors, the integrity of our most treasured traditions and institutions, and how our response might contribute to a more just world. When we focus solely on the status of the tainted thinker and their work, much of the ethical picture fades from view.

Three years prior to Jesus’ crucifixion, he had launched a public movement in the violent society of the Roman Empire. He said that God’s kingdom was coming close, and he invited people to rethink their lives in light of it. His message revolved around a teaching that we desperately need to embrace today. That teaching, however, is also what led to his crucifixion.

On Maundy Thursday of Holy Week, we remember how Jesus and his disciples celebrated the Passover meal, transforming it into what we now celebrate as communion. The word “maundy” originates in the Latin mandatum, in reference to the mandate Jesus gives his disciples that night: “A new commandment I give unto you that you love one another” (John 13:34). Just before the meal, Jesus engages in an act of loving service and humility: washing the disciple’s feet.

This selfless act contrasts sharply with the shameful spectacle that has dominated recent news: the indictment and arraignment of former President Donald Trump.

I wish the world could read a thoroughly-researched, 900-page report from the women who Vanier preyed on; a full report, written in their own handwriting and spoken in their own voices about what he took from them. I wish the world could understand that the women are more than the sorrow brought about by this injustice. They are resilient, and whether we know them or not, their stories are a part of our story — the story of L’Arche as well as the broader human story.

Currently, I am a prisoner willingly serving a prison term for terrible crimes I committed a long time ago and self-reported some years past. This prison season has been the brightest darkness I've ever known. Prisoners are exiled from healthy community and forced to grapple with toxic shame in isolation. The same is accompanied by a pervasive loneliness that can be overwhelming.

During the medieval Good Friday service, Christians prayed for the “perfidious” — or deceitful — Jews that God might “remove the veil from their hearts so that they would know Jesus Christ.” In another part of the service, a crucifix was placed in front of the congregation so people could venerate the crucified body of Jesus.

I am not sure what else needs to happen so the entire U.S. church wakes up to the realities of the evils entrenched in our immigration system. Honoring the dignity of all people is our calling as Christians; no other entity is tasked with recognizing the image of God in every person. Our Latine brothers and sisters are leading the way, but the whole church should be outraged; we should be demonstrating without ceasing. We should not let people sleep until they see the humanity of every migrant.

Prior to attending seminary, I always viewed my Christian faith as tethered to my Black identity. Growing up as a first-generation Nigerian American, my parents taught me that having a relationship with God was nonnegotiable and necessary to thrive in every area of life. And in moments when I experienced racial discrimination, misogynoir, and challenging seasons of my life, my Christian faith has been there to sustain me. Spiritual practices such as praying and reading the Bible not only grounded me in my faith, but also affirmed my experiences as a Black woman and helped me regain a sense of who I am and who God is. But I knew my own experience with faith only represented one perspective on Black spirituality.

In my last years of college before I started seminary, I was in the wilderness. I had to finally grapple with feelings I’d been trying to avoid for years: that I was attracted to women, and that something about the gender I’d been assigned wasn’t right.

“You’ve never heard of womanist theology?!” My colleague Rev. Moya Harris looked at me with a mix of excitement and incredulity. This wasn’t unusual: Through I attended parochial schools and Catholic colleges, I’m a relative newbie to the wider world of faith-based organizations and advocacy — and thus my work frequently involves googling the names of theologians, denominations, and Christian leaders I’ve never heard of before. I love this environment of continued learning, but when I learned about womanist theology, I realized I had been missing a key element of my faith: the liberatory and healing nature of God.

First-time director Jordan has a lot to say about masculinity, particularly Black masculinity. Ultimately, Creed III offers a hopeful vision of a future for Black men that doesn’t live in the shadow of white supremacy.

I’ve never felt the certainty of divine presence in my life. I’ve chased it, I’ve wanted it, but I have never felt it. My religious experience is more akin to poet and essayist Christian Wiman’s experience. Wiman describes God as “... my bright abyss / Into which all my longing will not go.” I persistently feel my attempts to address God are met with emptiness, and yet I find it impossible to abandon the language of religion. What do I do about this “bright abyss” that I seek but never find? What do I make of this divine glow on the horizon of my experience that all but fades away when I seek it?

Every year, in the final months of winter before the warmth and longer daylight of spring fully take hold, my spirit needs renewal, sometimes even revival. For others, this season can be characterized by a general sense of malaise or just feeling blah. Daylight saving time never helps. And for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, this season also falls during the solemn season of Lent.

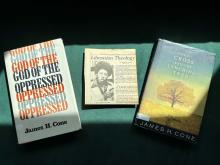

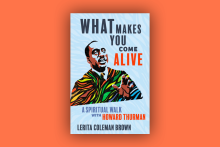

As I began to read Lerita Coleman Brown’s new book, What Makes You Come Alive: A Spiritual Walk with Howard Thurman, I received an overwhelming assurance that there was something to learn in this book about our turbulent and violent times.