Voting

I GREW UP in Gulfport, Miss., which is on the coast, and my parents are from Hattiesburg, which is about an hour north up Highway 49. On weekends, my mom and dad would pile the six of us in the car, and we would visit my grandparents.

My grandparents’ names always caused some confusion in our family because my grandmother was Wilter and my grandfather was Walter, but they called each other Bill and Jim. I didn’t know who was who. And my grandmother—Wilter, Bill, and known affectionately by my grandfather as Sugar Honey—she and my grandfather raised us with my parents to understand where we came from.

They wanted us to understand that my great-grandmother Moo Moo, who lived in the little house next to theirs, was two generations removed from slavery. Her grandparents had been slaves. Her parents had been sharecroppers. If you were lucky, you would get there in time to help her shell peas and listen to the stories that she would tell. You could listen to the history from her mouth, and you knew you were in a sacred place sitting on that front porch. When I got ready to run for office, I was bringing them with me, and I didn’t quite understand it.

But in September 2018, as the election for Georgia’s governor was heating up and stories were flying around about voter suppression, I went home to Mississippi because my grandmother was ailing. My grandfather had passed away in 2011, but my grandmother, she was on the edge. Grandma had a rocking chair recliner she sat in most of the day and a bed right beside it. When you came in the room, you sat on the edge of the bed and took her hand—because she was watching MSNBC, and you didn’t want to interrupt her learning why she was mad that day.

When she got to a place where she was going to acknowledge your presence, she would mute the television and turn to you. As I sat by her bedside, her hand was frailer than it had ever been before. The skin was papery and soft. The bones were brittle, and I could feel every one of them; I knew I was holding my grandmother’s hand for one of the last times. But she didn’t want to talk about how she was ailing; she wanted to talk about my election. She asked me if I was taking care of her baby, meaning me. I said, “Grandma, I’m doing my best. But I’m worried, because this man I’m running against is in charge of the election. He’s the scorekeeper, he’s the contestant, he’s doing the box copy, he’s the umpire, and it’s going to be hard.” And she said, “Have you done what you can?” I said, “Yes ma’am.” “Let me tell you about the first time I voted,” she said.

These types of failures in the voting process may become additional tools in the arsenal of voter suppression, and the Black community must be prepared.

I CAN NAME Emma’s favorite foods: roasted sweet potatoes and acai smoothie bowls. I’ve spent hours with her two sisters and classmates. We’ve traveled across the country together and danced to all her most-loved songs.

Week after week, with one tap on my screen, I instantly enter Emma’s world. As we laugh and smile at each other, it feels as if I am spending time with a friend, albeit a virtual one.

Emma Abrahamson is one of the countless Generation Z video bloggers on YouTube (some with tens of millions of followers) who are re-creating the nature of human friendship and experience.

The next presidential election will include a wave of Gen Zers voting for the first time. Who are they? What do they care about?

Beginning with those born in 1995, the same year as the commercial internet, Gen Zers only know a life of navigating multiple realities. While I (a millennial) am part of the generation shaped by the arrival of instant communication, Gen Z is the generation shaped by the arrival of instant experience. They are constantly living on the cusp of the virtual and the physical—and, just like Emma, draw the rest of us in.

Some worry that such a technology-centered existence, filled with YouTube friends and instantaneous everything, leaves young people isolated and ill-equipped to live with uncertainty. Researchers claim it is leading to the highest rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide ever recorded.

According to the website FiveThirtyEight, more than half (54 percent) of older white evangelical Christians see immigrants as a burden on American society. But 66 percent of young white evangelical Christians (age 18-34) say that the U.S. is strengthened by immigrants. Only 32 percent of older white evangelical seniors (age 65+) agree.

“They struggle in the absence of information.”

With Brexit, the chumocrats who drew borders from India to Ireland are getting a taste of their own medicine.

Souls to the Polls is a time-honored tradition, often led by clergy, to activate and engage congregants to exercise their right to vote that starts long before Election Day. It is a mobilization strategy to make the process of voting easier for their congregants. But sadly, voter suppression efforts targeting minorities in subtle and overt ways continue to make Souls to the Polls a critical service — placing the burden of voter education and empowerment on the backs of churches and other civil society organizations, not the government.

Despite the split decision of this election— with the House going to the Democrats and the Senate to Republicans — the results do not mean it will be easy to prevent Trump from making further dangerous, corrupt, or autocratic moves over the next two years. But the election does mean that any moves like these will be challenged by key oversight committees in the House; at least after the new Congress is seated on January — but the lame duck session between now and then becomes a dangerous time to see what Donald Trump may try to do.

In a time like this, prayer is not perfunctory, an add on, or a brief closing to a meeting. Rather it is an opening to what indeed has now become “spiritual warfare” as the New Testament describes.

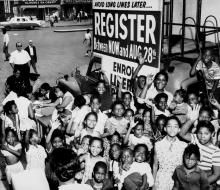

In the black community, voting has always been complicated.

We voted and yet you lynched us.

We voted and yet you incarcerated us.

We voted and you poisoned our water.

I’ll treat the earth as sacred space

Name violence a vile disgrace.

Build a world of justice and peace

Help the oppressed find release.

Our faith is offended by these assaults that contradict the biblical commands to love and protect our neighbors. Our conscience is seared by the lies and strategies of hateful politics that will lead to more and more violence in this country and put the soul of our nation in jeopardy. Words matter and hateful words do lead to violence. Our commitment to our brothers and sisters under attack will lead us to pray, stand, act, and vote against the politics of fear and hate, because of our faith and patriotism.

In the richest nation in the history of the world, 140 million Americans are poor or low income — one emergency away from not being able to meet their basic needs. We cannot be distracted by arguments about which president or party in recent history had more quarters with over 4 percent economic growth while Congress seriously considers cuts to programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Donald Trump is not on the ballot this November, but the fate of poor people in America certainly is. In state legislature and congressional races, we must ask ourselves which candidates are willing to challenge the lies that keep millions of our neighbors in poverty.

1. Trump Cannot Define Away my Existence

The administration seems to think transgender people like me are as imaginary as hippogriffs.

2. The Secret Anxiety of the Upwardly Mobile

Children who do better than their parents often must choose between blending in and standing out.

According to a report earlier this week from The Associated Press, more than 53,000 voter registration applications have been sitting on hold with Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp’s office. The people on the list are predominantly black, and may not even know their voter registration has been held up.

WHAT DOES ELECTION-RIGGING LOOK LIKE? Often, on its face, it looks quite benign.

Take Ohio. The official elections website of Ohio’s secretary of state proclaims that “all eligible Ohioans have equal access to one of the best elections systems in the country.”

But “equal access” isn’t always what it appears.

Ohio provides only one polling station per county for early voting—which on the surface gives the impression that the system is fair and equitable. But—and here’s the rub—the counties are fundamentally different. For instance, Pickaway County, just south of Columbus, has fewer than 60,000 residents. Hamilton County, where Cincinnati is located, has a population of more than 800,000 people. But each county only has one early-voting station.

The results have been predictable—and have not been race-neutral. In the 2012 presidential election, there were no lines to vote early in Pickaway County, which is 94.5 percent white. But Hamilton County, with its 206,000 African-American residents, had a line that stretched a quarter mile. According to UrbanCincy.com, voters in Cincinnati reported wait times of more than four hours, and other urban areas, such as Cleveland and Columbus, faced similar obstacles. (Comparable delays occurred in 2016.) The Republican Party chair for Columbus’ county defended the long waits, telling the Columbus Dispatch, “I guess I really actually feel we shouldn’t contort the voting process to accommodate the urban—read African American—voter turnout machine.”

Unfortunately, Ohio is not alone. According to a report in Mother Jones titled “Even Without Voter ID Laws, Minority Voters Face More Hurdles to Casting Ballots,” African Americans across the country waited about twice as long to vote as did white people in the 2012 election—and the trends are getting worse, not better. A study by the Brennan Center for Justice found a strong correlation between precincts with significant minority populations and polling places that have a shortage of resources, such as voting machines and poll workers—and these are big factors in long voting lines, which tend to depress voter turnout. In South Carolina, the study found, areas with the longest waits had more than twice the percentage of African-American voters than the state as a whole.

Erecting obstacles to voting—for some

Restrictions on early voting aren’t the only obstacles and inconveniences put in place in recent years. For instance, an official in Randolph County, Ga., recently proposed closing seven of the nine polling places in the county, which happens to be majority black. For many of the county’s residents, that would mean the nearest polling place would be as much as 10 miles away. For every tenth of a mile that a polling place is moved from an African-American community, the black voter turnout goes down by .5 percent, especially in poor areas where transportation options are limited. Making polling places less accessible depresses the black turnout rate. (After an outcry, Randolph County backed off its plans to eliminate polling places for the 2018 midterms.)

The “consolidation” (read: closing) of polling places isn’t limited to Georgia. After the Shelby County v. Holder decision by the U.S. Supreme Court that gutted the Voting Rights Act, jurisdictions that used to have to go under preclearance—places that were required to have their voting changes okayed by the Department of Justice because of their problematic histories of racial discrimination—had 868 fewer polling places in the 2016 election than they did before the court’s ruling.

A Deeply Moral Act

Voting is a decisive statement of Christian faith that I matter, justice matters, and others matter.

by Richard Rohr

Low voter turnout is generally a sign of a demoralized society, and people of power feed on that demoralization, knowing that they can then easily gerrymander, suppress and limit voting rights, and give elections to the rule of money and lobbyists—and there will be little outcry, because there is so little trust or even interest in the whole system anyway.

Yet this is largely where the U.S. is today.

The powers that control society are quite happy that it is always minorities of all stripes that first feel this powerlessness and this demoralization. Since the early days of representative government, it has been believed that democracy would only work if there was a truly free and informed citizenry. We presently seem to lack both in the U.S. This is why voting is a deeply moral act for me—in rebuilding confidence and encouraging an intelligent and hope-filled society. It is also a decisive act of Christian faith that I matter, society matters, justice matters, and others matter.

Not to vote is to hand our power and our dignity over to people who fear actual freedom, honest intelligence, and faith in the very goodness of humanity.

Voting for Change

I vote because many of my brothers and sisters can’t.

by Myrna Pérez

I vote for a lot of reasons. I love joining my fellow citizens in a community-minded act. I love having a say in picking the leaders who get to decide on things that matter to me. Increasingly, I love to vote and feel compelled to vote because I know there are about 4.5 million Americans living and working in communities across the country who cannot because they have a criminal conviction in their past.

The purpose of Lawyers and Collars is to equip and empower pastors and local church leaders to work alongside lawyers to protect vulnerable citizens at voting precincts. Together, we can provide a legal and moral presence against voter suppression, intimidation, and harassment that are expected to rise in the 2018 midterm elections. The campaign welcomes the involvement of imams, rabbis, and other faith leaders.

IN A TIME of voter suppression, gerrymandering, and persistent political scandals, it’s easy to wonder if voting matters anymore. Many people don’t vote at all, citing everything from long lines to ethical squeamishness. But not voting is still a vote, with real consequences for our democracy. Here are a few ways to reframe the way we think about voting:

1. Make it more than a vote

Voting is just one aspect of civic participation. Extend the action by engaging in your community. Participate in events at recreation centers, run for school board, and attend public forums on local policy. Don’t make a ballot the only place you voice concerns—communicate with local officials and speak up at city council meetings. Think wisely about how you spend your money and your time, and make civic commitment an everyday mindset rather than an annual event.

2. Think globally

Thinking about one’s individual ballot, by itself, can make voting feel uncomfortably personal and easy to dismiss. Instead, consider how your vote impacts those outside the voting booth. Many people are unable to vote in some or all elections, including legal permanent residents, U.S. citizens living in U.S. territories, and, in many states, formerly incarcerated persons. Think critically about how proposed policies will impact these individuals. Be mindful of a candidate’s disposition toward the world. U.S. foreign policy is felt worldwide—vote with our global neighbors in mind.

3. Recognize that voting is an extension of your faith

While you won’t find a Bible verse commanding Christians to vote, we are called to care for marginalized communities that may be adversely affected by social policies. Sometimes we have strong affinity for a candidate, and other times we feel that one is the lesser of two evils. To vote is to recognize that community is messy and people who run for political office are rarely perfect. In the moment, voting doesn’t always seem worthwhile or meaningful, but it is an act of hope, an expression of trust in the power of collective agency to build a more just future.

CAL MORRIS WAS 20 and studying religion at Samford University in Birmingham, Ala., when he offered a stranger a ride. As they crested the Red Mountain Expressway, dropping into downtown, Morris, who’s white, and his passenger, a black man old enough to be his grandfather, talked about how bad public transportation in the city was, how hard it was to get to work without your own ride.

The next morning, in his religion classes, Morris announced he was raising money to buy his new acquaintance a car. “I was thinking: ‘I go to Samford. ... It’s one of the richest places ever,’” Morris recently remembered. “I figured I could get the guy an $800 El Camino.” Instead, his professors and peers offered calls for prayer. It was his friends at work, not his classmates, who knew what it was like to need a break, and so they pooled enough money for the car.

That was two decades ago. The “El Camino incident” set off a series of revelations for the kid raised middle class in north Alabama by evangelical parents who never really talked politics at home or at church. Morris began to see how racial and economic disparity were tied to public policy, and how his conservative Christian friends tended to ignore or fetishize vulnerable folks as nothing but needy.

He isolated himself from the evangelical community. He moved into his car in the woods with his dog. He abandoned the notion of leading a church and kept working in coffee shops, like the one where he’d met the old man, searching for ways to build the kind of community he idolized in Wendell Berry novels, searching for ways to be of use without any white savior hang-ups.

Now, more than ever, we need political candidates and elected officials on both sides of the aisle who value the rich and diverse tapestry of this nation and seek to build bridges instead of walls. And while we deserve candidates who exhibit civility and respect in their campaigns and governance, this has never been a guaranteed right. We must be committed and courageous enough to speak out for mutual respect and decency. We must challenge all leaders and hold them accountable to the values presented throughout the gospel.